Being a middle-of-the-pack athlete doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from high-tech metabolic testing. Our reporter went through the paces to learn more.

An athlete without reliable data is like a lost hiker without a map. They don’t know where they are, can’t see where they’re going, and have no idea how to get to their destination. So they wander aimlessly.

In seeking improvement and mastery of your craft, one can generally improve performance via three avenues: gaining technical skills through coaching, video analysis, and improved body awareness; strategizing based on what worked, what didn’t, and why; and making physiological improvements. In the physiological improvements bucket, the most accurate way to gather accurate and actionable data is through lab testing.

My athletic career in endurance sports never really got off of the ground. When it became clear that I was good at racing crits on a road bike, a pattern started to emerge. That pattern carried itself into Olympic Sprint kayaking — a sub-two-minute event at the 500-meter distance.

Still, all-day, epic road or mountain bike rides in stunning surroundings are something I enjoy immensely. I race occasionally, and sometimes I tap into this place where my body’s ability to make horsepower seems unlimited. That transformative lightness and feeling of power, more than anything, is what I end up chasing.

And that chase led me into the heart of the cutting-edge world of performance training.

Durango Performance Center

Durango, Colorado, is blessed with some of the best cycling in the country, from road to mountain, desert, and high alpine. Consequently, Durango attracts genetic freaks who excel in international competition. And those freaks and their training regimens are supported by the Durango Performance Center at Fort Lewis College.

For about the cost of two new high-end tires, Rotem Ishay, the Performance Center’s director and exercise specialist, conducts world-class performance and metabolic testing on recreational athletes such as myself. Game on.

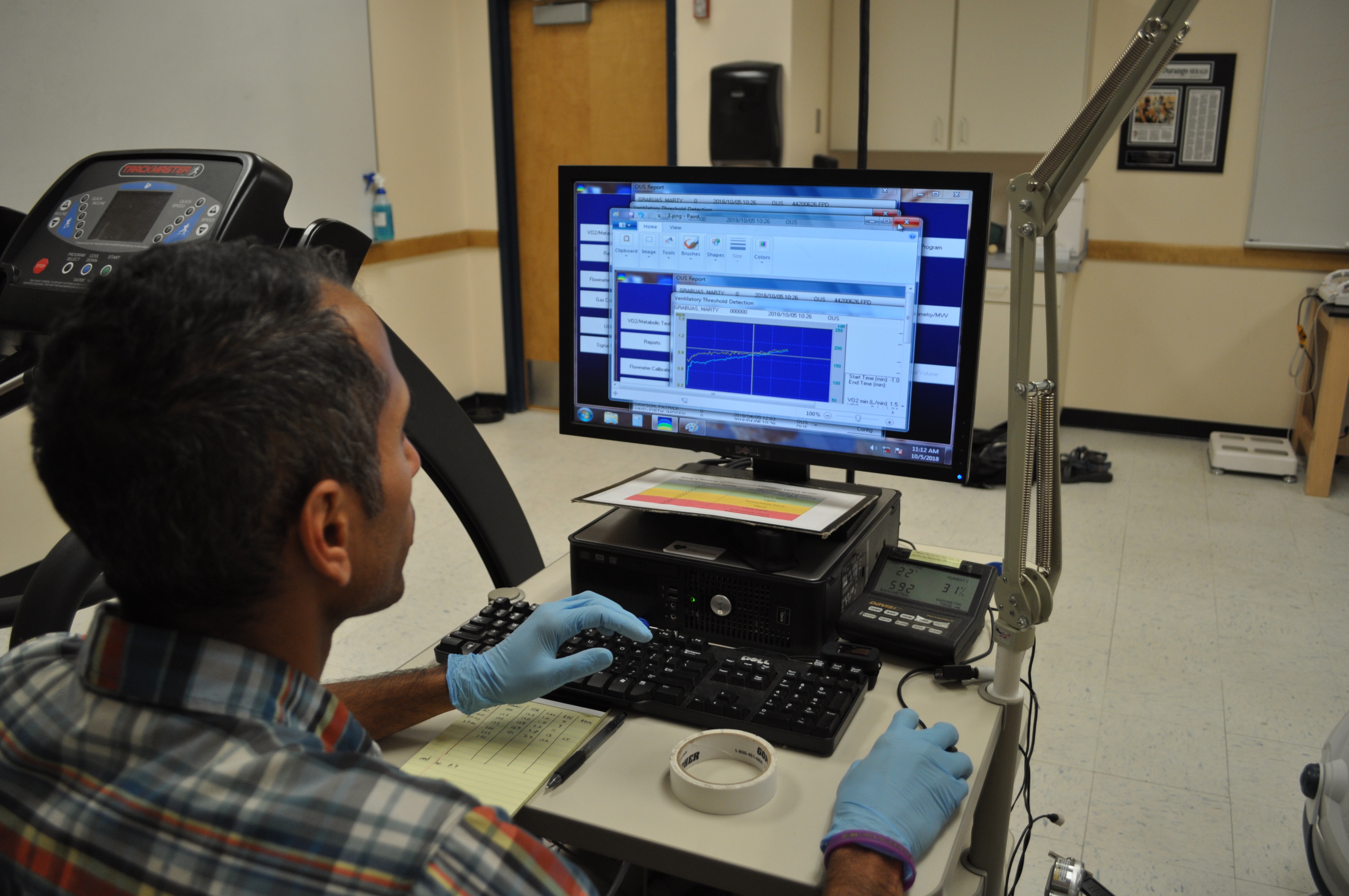

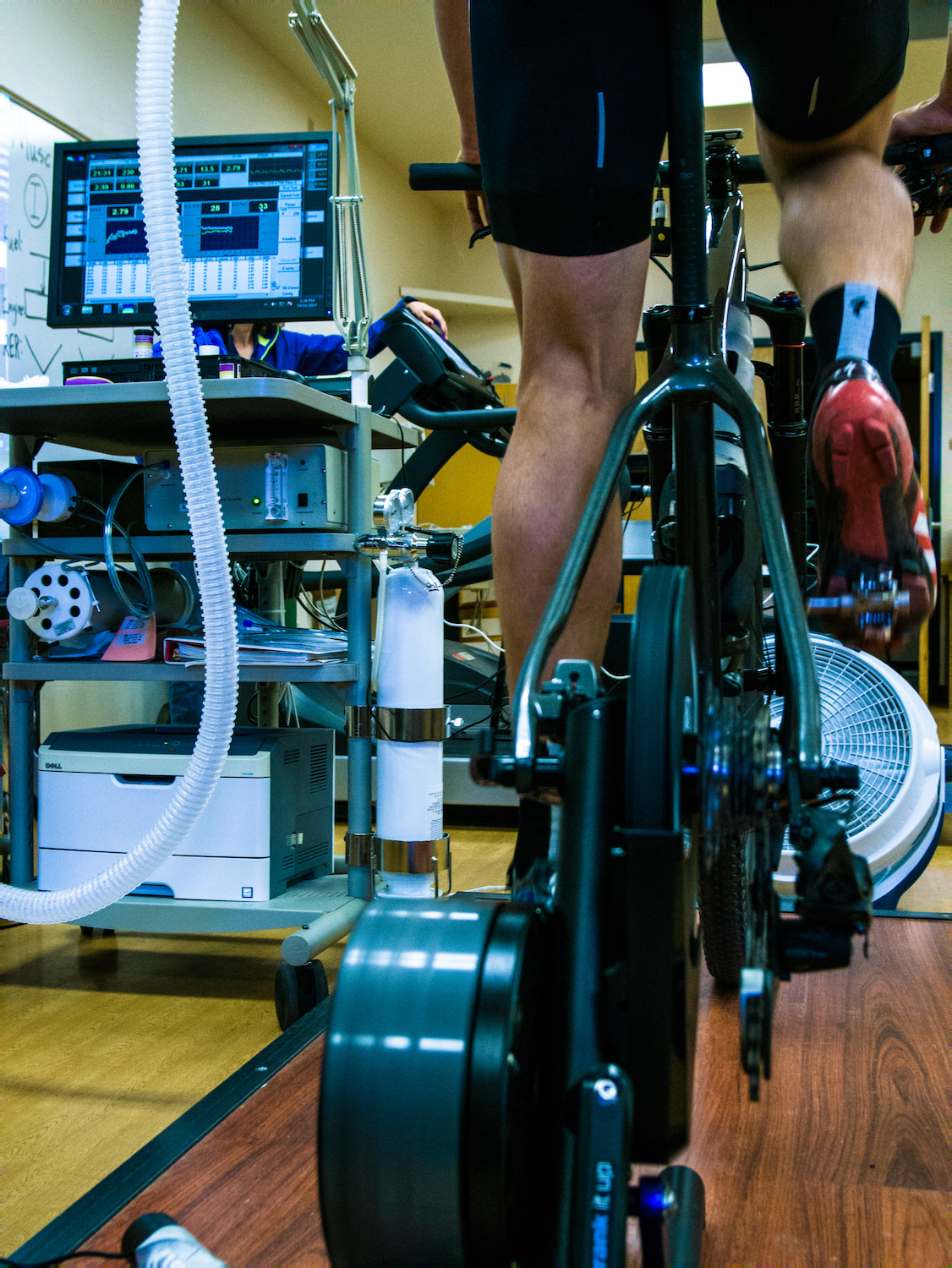

Fort Lewis College’s Skyhawk building, next to the college’s football field, houses the Performance Center. The room itself is nondescript except for the computer equipment sitting center stage, with a bike trainer on one side and treadmill on the other.

Metabolic Testing: What It’s Like

Rotem fit my training bike to the equipment. Then I warmed up for about 15 minutes, during which he calibrated the equipment. After that, he fit me with a mask that formed an airtight seal to my face, which took some time. The mask fed my exhaled air to the computer, which collected data on O2 consumption, fat oxidation, carbohydrate oxidation, and respiratory exchange ratio.

While the mask and computer were doing their thing, a monitor also measured my heart rate. Every five minutes, after each new level of intensity was complete, Rotem took a small blood sample to measure blood lactate levels. He poked my earlobe multiple times to create adequate blood seepage.

According to Rotem, depending on the level of athlete he is testing, he uses one of two testing protocols. In both cases, all other metrics are measured against watt output. In my case, like all recreational athletes, my incremental workload increase came in 25-watt chunks.

Testing starts on the low end of a subject’s watt output to collect as many clean data points as possible. Elite athletes — those competing on the world stage — experience a bump in the watt output they have to produce, equal to 0.5 watts per kilogram of body weight.

Each chunk lasts five minutes. While many test protocols use two minutes, Rotem said various metabolic markers have not leveled off at two minutes, and the results of each time chunk have not reached their biological conclusion. Essentially, the subject’s markers don’t plateau at two minutes. Collecting that data at two-minute intervals leads to misrepresentations of what is happening metabolically.

Test Underway

I had a history of training with power meters and had done significant baseline testing in the past, so I had an idea of what to expect. If anything, power meter training revealed that I was going too hard on easy days, which didn’t allow adequate recovery.

I had a history of training with power meters and had done significant baseline testing in the past, so I had an idea of what to expect. If anything, power meter training revealed that I was going too hard on easy days, which didn’t allow adequate recovery.

On long, loping five-hour rides I would come to a short, punchy hill and throw down 650 watts to clear it when I should have been staying under 140 watts. My fast-twitch self was overriding my training goals for the day.

With the mask on and the test underway, the sensation was identical to just spinning on a trainer, albeit with a breathing apparatus on. Someone milking my earlobe for a drop of blood at the end of every interval was also something I don’t experience while on a trainer in my garage.

As the test progressed, the watt output I had to meet increased every five minutes. As intensity increased, I quickly found out there was a technique to breathing through the mask. With long, controlled breaths, I was able to bring enough air in to supply my body with the O2 it started to crave. If I interrupted that rhythm, it felt uncomfortably like someone putting a pillow over my face.

During my pretest briefing, Rotem referenced the end of the test several times. I asked how he would know when the test ends, and the answer was subjective: It could be when the test subject can only spin a cadence of 70, or when the test subject calls it quits.

In my case, with vision dimming, and with tunnel vision coming on, the end was near. Another 25-watt increase and another five minutes probably wouldn’t yield a data point that would help, and I’d likely pass out.

Results

Rotem quickly removed the mask, and while I was crumpled over my bike, he said, “Wow!” Apparently, my anaerobic output was in the top percentile of subjects he has tested, and off the charts for my age group. I knew I was anaerobically strong, but not to such an extent. The flip side was that my aerobic energy system sucked even more than I could have imagined.

Early in the process, Rotem said, “Data are seeds, but what can you grow with them?” Data by itself is useless for any application from athletic performance to finance to market segmentation. Being able to put that data into action is what matters, and that was our next step.

Using the data collected, Rotem laid out a training plan for me to follow for the winter. Each test subject at the Performance Center receives this prescription at the end of the test, or collaboration with their coach. It’s based on the subject’s goals for races or rides, the distances and altitudes they cover, how much time a person has to devote each week to training, and how far out the event is.

In my case, I had an idea of what I needed. Rotem prescribed a program to build my aerobic energy system while not compromising my sprinting ability.

It should be noted that physiological fitness for cycling is only one factor in performance. There are other factors at work: Are you able to relax on descents to lower your heart rate? Can you tactically take advantage of other riders?

And then there are elements of free speed: Have you conducted rolling tests to determine your optimal tire pressure? Do you know the most aerodynamic positioning on your bike? Or are you guessing?

Eliminating guesswork increases efficiency. A few points here, a few points there, shedding a few pounds of body fat, and all of a sudden, you’re dropping vehicles (or competitors) on a 28mph uphill more frequently.

Taking My ‘Prescription’

I have my prescription, and I won’t know its full effects for months. It doesn’t mean I’ll spend all my rides staring at my watt meter. But it does mean that I have accurate information to plot my winter training plan.

With the clarity and objectivity data brings, it’s now up to me to focus on my personal commitment to bring more intention to my daily rides. No more excuses. No more BS. I know what I have to do and when I have to do it.

I will never be a climber and be able to pace the racers who weigh 135 pounds on sustained climbs. However, with Rotem’s guidance, I can increase my body’s ability to convert a bit more fat to energy. And with objective metrics on my strengths and weaknesses, I can more accurately leverage those tactically and strategically. Like in the past, if the race comes down to the last 200 meters, I am a strong contender.

Performance Testing: Jumpstart Your Fitness Goals

Like most things in life, excelling in any endeavor is about a process. If you have a goal and good information on how to execute the process, you will likely reach your goal. I’m confident that the seeds the Durango Performance Center provided me will bring more stoke to my cycling.

While not everyone is fortunate enough to have the Durango Performance Center down the street from them, many universities and medical clinics are set up to provide this service. A quick Google search for “lactate metabolic profiles cyclists” brought up a number of clinics and labs across the country.

Cost for this testing at the Durango Performance Center was $195. A few phone calls revealed this is at the low end of the scale, with most charging $200 or more. A clinic in Manhattan quoted close to $400. In this age of dwindling medical benefits, none of the clinics we spoke to said performance testing was covered by medical insurance.

Still, if you’re considering buying a pair of $2,500 carbon wheels, performance testing would be a better place to start. Those carbon wheels may make your average times faster, but they won’t make you a more efficient cyclist. Testing, and following through on a training program, will.