Transcript:

Adam (01:46.91)

And we’re rolling on the gear junkie podcast. My guest today is David Stover, co-founder of BUREO. David, it is a pleasure to meet you.

David Stover (01:56.866)

Thanks Adam, happy to be here.

Adam (01:59.846)

Let’s start at the beginning. My producer Luke was more familiar with the company than I was at the outset. So I would love to hear What is Bureo? How do you describe the company you co-founded?

David Stover (02:13.802)

Yeah, I mean, it’s been a long journey. Boreo started in 2012, 2013. Initially, we were a company focused on building our own products from recycled waste, and we target recycled fishing nets. Our kind of company has evolved on the same mission of ending fishing net pollution. We’ve been focused on setting up collection points and working on a recycling process to basically bring a problem in the ocean, which is discarded fishing nets into products and be a solution for replacing a virgin or new plastics with an alternative recycled feedstock. And so 10 years later, yeah, we’ve jumped from just making skateboards and sunglasses and some simple products to trying to disrupt kind of this behemoth supply chain for plastics that is ubiquitous across all products that we have.

Adam (03:09.98)

What put fishing nets in this particular issue on your radar in the first place?

David Stover (03:15.754)

Yeah, kind of like we kind of stumbled into fishing nets to be honest. Um, in the beginning, like everyone else that was starting to try to understand where plastic was coming from the ocean. Like we all grew up around the water and traveling and surfing and like, we started to become aware of it. I’d say in like 2008, 2010 timeframe. And then once you start seeing plastic in the ocean, you can’t not see it. Right. Every time you go to the beach, you see it on the beach. Every time you’re on a sidewalk. You think about a storm drain and like that, we went through that transformation in the beginning and started asking questions about, okay, can we just collect all this material? And like naively, we thought we could just scoop everything up and melt it down to make a product. But then when you start getting into product design engineering, you realize, hey, we need to have like a quality feedstock that’s going into a product. If that’s a surf fin or a skateboard that you’re going to stand on or put through an aggressive turn, you can’t have that product failing. And so Kevin and our team, who’s a design engineer, was really focused on kind of the mechanical properties of the material. And so we connected that to like, what if we could just make a difference for one type of this pollution? And we started asking questions about like, what makes up plastic in the ocean? We saw the bottles, see cigarettes and lighters and toothbrushes and all these other waste streams and we couldn’t tackle it all. So we said, what is something that someone’s not doing something about now? And we talked to NOAA and researchers in the US and nonprofits at the time to understand where this plastic was coming from. Kind of a funny story that Ben on our team was talking to fisheries in Chile. He was doing a study on their footprint, their environmental footprint. So worried about burning fuel and types of materials they were using. And he was asking them like what types of plastics are you picking up in your nets? You know, like what are you seeing in the ocean? And they came back and they’re like, well, all of our fishing gear is plastic and we don’t have anything to do with that. And we see nets and buoys and ropes. And that was kind of like, oh, okay, well, maybe this is something we could target. And then we started looking at the surveys and, you know, start asking questions and go to fishing ports and this waste is everywhere. And so that kind of became like, this is our kind of niche and open water that we’ll focus on because there’s a lot of other solutions being put in place for various types of plastic.

Adam (05:45.058)

Before BUREO, what were you doing and who were you that when you saw plastic pollution, like all of us have seen that you were able to like, oh, I’m going to dive down this rabbit hole and see where it takes me. Like where were you at the time?

David Stover (06:02.846)

Yeah, I mean, I’d say luckily, like Ben and Kevin co-founders on the team, you know, friends of mine. And so like I’m everyone, every time you hear a founder story with like one person, it’s like, I believe it, but I always have skepticism because I know how much like it takes of like group brainstorming. And I think every founder, if you talk to them, you know, they’re talking to friends, they’re kicking around ideas with advisors, you know, personally, for me, I’d say that I had a very.

close connection to the environment. I kind of had a unique upbringing on a small island here in the US and spent a lot of time around the water. You know, from a young age, I wouldn’t have considered myself an environmentalist at all. But in the community that I lived in, you know, it was just the type of place where if you saw trash, you picked it up. You know, certainly like if you went to a beach, like luckily it was pretty pristine. And when I left that kind of bubble of an environment.

Um, you know, working internationally, you know, started in Los Angeles and then took a job in Sydney. Once I was in Sydney, I did some traveling for surfing. I was in Bali and New Zealand. And like at that time of my life, in my like early twenties, I started to understand more like, okay, what is kind of the impacts this planet, you know, what is the impact that we’re having? And like plastic pollution was one that just stuck with me everywhere I went. Cause like, you know, spending time in the water, whether you’re free diving, I was swimming.

kind of open ocean and surfing. It’s like, you’re so close to that issue that like, even if you know about pollution, you might just drive by it on the road. But like when you enter the environment and like you’re in that environment, you take it like really personally. And at that time, Kevin and Ben were, you know, in their early to mid twenties as well. We were just kind of brainstorming like, what could we do about this? You know, is it a nonprofit? Do we just take a career break and do something differently? But luckily like education wise,

We’re all engineers, so we knew enough about plastic to be dangerous. I wouldn’t say that we’re experts, but generally knew how products were made. You’re taking and melting down plastic and you’re injecting it, or you’re extruding it for products. So we knew enough to be dangerous with that and started brainstorming. Like, can we make a wetsuit bin? Do we just make surf bins? We had a lot of ideas early on for how we could convert that plastic.

Adam (08:28.294)

Did you have, were you fairly confident at the time that there was enough demand for end product that this could be used for that you were onto something or at that time had like recycled ocean plastic not been the in material that it is now?

David Stover (08:50.486)

Yeah, I would say we were confident we wanted to do something mission driven. And at that point in our career, we were able to take a risk that if it didn’t work out, we would jump back into something else at the very beginning. Um, from like talking to companies at the time. And we had some specific examples where companies even said, Hey, I’ve tried this recycled thing, it didn’t work out the market’s not ready. People aren’t into this. I don’t.

I don’t know if the term ocean plastic existed in 2009, 2010, but I don’t think we heard about it for a couple of years after that. But I think when we launched our first product, the skateboard, we weren’t confident that the market was going to respond to that. We thought that was obviously our thesis going in that people will care about this. But to be honest, we were a little bit like building a niche skateboard company. To us, that was exciting. I think in reality, like…

there was lessons learned through that where one of the biggest things was like the people were more on board with like the mission and what we were doing and the idea of like converting these nets into a product than they were necessarily into skateboarding. And so that has kind of led to the transformation of like our whole company being based on collecting the waste and being a solution and really partnering now with companies that are kind of focused on quality products.

Adam (10:11.474)

How quickly did it go from skateboards in your initial idea to kind of blowing up and some major companies, Patagonia obviously, how quickly did it sort of explode to be what it is now and all the products that it’s in?

David Stover (10:29.462)

Yeah, I mean, relatively from like a volume growth perspective, I mean, we’re much more low growth modest compared to like when you think of like young companies and like if you’re a consumer products, like you’re looking at, you know, 5x, 10x growth, whatever you’re achieving. I mean, for us, like that first year, when we were just making skateboards, we were doing 10 tons of material, which is like half a shipping container of nets, which for us was an accomplishment.

And this past year in 2023, we did about 1650 tons of material, which is, you know, 80 to 100 shipping containers full of material. So it has kind of grown pretty broadly, but in those early years, you know, 2012 to 2016, we were like really low volume those four years where, you know, product design, designing molds, like making the product, running kickstarters, like going to wholesale, selling people on kind of the mission.

Luckily, Patagonia was a partner from the beginning. They saw what we were doing even with skateboards and, um, invested in offered support, but that kind of timeline to go from skateboards to say like a Patagonia jacket, that was a much longer fuse where, you know, they invested in 2014, um, and R and D for that really kicked off and like,

2016, 2017, and then that product didn’t really commercialize till 2021. So if you think about that, like seven year period of like recognizing what we were doing, kind of supporting us early on and then going through some R and D and then getting into products, it’s a really, it’s a really long time to get off the ground.

Adam (12:09.975)

How do you actually collect the nets and material?

David Stover (12:16.234)

Yeah. So I mean, Boreo really we’re responsible for operating that program. So, um, like we, our largest facility we just purchased in Chile, it’s, it’s 30,000 square feet. If anyone’s ever been to a recycling facility, um, a lot of similarities there, except that it’s only focused on fishing nets. Right. So we set that up. It’s a kind of a recycled foundry, if you will. They were pouring steel there at one point. So we have overhead cranes.

Uh, you know, we have several industrial equipment that’s installed to wash the nets, mechanically shred it and de-size it. And then we also manage the logistics from the port. So either we hire truckers directly to go and collect the waste where it’s accumulated. We have partnerships with fisheries where we set up collection points, um, where they accumulate material and then we go collect that and then our team, so our either contracted or our full-time employees.

they’re responsible for going through that material, breaking it down and starting the recycling process at one of our either leased or owned facilities.

Adam (13:20.878)

Is the reality that at the end of life, these nets are just discarded and they go wherever and end up on a beach? Is that typically how it works?

David Stover (13:31.914)

Yeah, I mean, like the fishing nets have some very specific indicators of why they become waste, but like this is a problem with everything. Like if you see truck tires on the side of the road or plastic coming from a household, like the way that waste gets into the environment is pretty complex. Fishing nets, most simply, like these nets are heavy, they’re dirty, and like honestly, fishermen are, you know, they’re trying to manage a waste like any other industry.

And unfortunately, like the nets wear out pretty regularly. It’s, it’s more like a consumable, right? The same way a tire tread rips through and you got to replace the tire. And then that becomes in a landfail or someone tries to recycle it. Fishing nets are a little bit more complex because they could be repaired on the boat. It could be repaired at a port. You got various sizes of a fishery. And so what we see is that waste can be accumulated, you know, on a beach.

could be accumulated near the dock, it could be in someone’s backyard. Certainly we see issues of nets making it to the marine environment or being unfortunately dumped in some cases, or there’s practices where those nets are kind of repurposed for a shellfish bag or like some way to accumulate fish where they might be left in the environment. So it’s not the intention of the fishery necessarily to dump it and get rid of it. It’s just a long kind of supply chain there where you have.

really a lack of responsible disposal. And so there’s various ways that material can leak and make it into kind of like more fragile ecosystems there.

Adam (15:03.73)

I feel like the outdoor industry, the general consumer, that the messaging that, hey, ocean plastic pollution is a problem, and that these discarded items, water bottles, fishing nets, et cetera, can be repurposed and recycled into high performance things that are as good, if not better, than other

performance synthetic materials. I think that messaging has succeeded and people are used to it, but I also wonder, is there an element of oversimplifying and does that narrative leave anything, any of the reality of all of that process and what is being done? Does it leave any of that out that the general public just does not comprehend?

David Stover (15:58.242)

Yeah, great question. And I’ll say this from being now working on a recycling project for 10 years. Like recycling will not solve the plastic problem on its own. Like we are never gonna produce 100% of products from fully recycled material. Like we need, like I kind of like, you always gotta obviously consider new technologies, new materials. Like we need like a multi-pronged approach to kind of reduce our impact.

Adam (16:11.196)

Huh.

David Stover (16:27.23)

And if you think about the outdoor industry, it’s not about, are you choosing a biomaterial? Are you looking at biodegradability? Are you looking at natural fibers? Are you looking at recycled materials? Are you doing all of those things? And I think that we really focus on, is the function you need for a product, whether that’s hardware or soft good, does that meet the material going into it? Not everything needs to be plastic.

And I think that like a criticism to the outdoor industry is they’ve probably converted too many products to plastic, even if it’s recycled or not. And like, we should still be looking at natural fibers for a lot of cases. And certainly like plastic has functionality for being lightweight for, you know, certainly waterproof and performance and not absorbing sweat. Like we should be still utilizing that in the right way. But I think that like putting all of the attention into like

Recycle plastic is wrong. Like I think we need to kind of diversify and look at that in small cases Specifically to your question, I think that also the apparel industry is looking at this now But being more transparent about like where is that plastic coming from? What is the actual impact of that? How are you sure that the story that you’re telling to the market is truthful, you know, like are you positive? Where that material came from? Are you positive that it is what you say it is? and I think that that’s something that

the industry is exposing now and kind of requiring certifications and making sure that consumers can really buy into these campaigns because a lot of them are great. It’s just, it’s hard sometimes for the consumer to like read between all the noise when every single product somehow has a sustainable backing to it, you know,

Adam (18:05.939)

Thanks for watching!

Adam (18:10.859)

Yeah, because every single tag on a garment is designed to make a shopper feel good. Every single one of them is broadcasting something positive, but also, and I navigate this as an editor when we get any number of press releases about whatever, what is the context here? How is this not making more noise and how is it actually giving substance there? And I don’t know that I have the answer.

I guess what I’m wondering is, is I think I’m guilty of having this notion that, all right, you know, there’s gyres or big clusters of plastic and we go by and we scoop it up and then we dump that off at this cool facility that does stuff. But as you pull that thread, you’re like, well, who has the boat? Like who’s actually cleaning up? Are you hiring endless employees to comb across beaches, to pick up these nets and other trash, like the realities of how this work are.

David Stover (18:57.805)

Yeah.

Adam (19:07.874)

I think I perceive that they’re mind boggling. Am I taking it too far? Is that all, is that all real?

David Stover (19:14.794)

No, it’s real. I mean, I think that like cleanup efforts are important. And I, but I don’t think there’s a solution to kind of production and like building great products. I think it’s a, it’s something we should be doing along with capturing that waste at the source. And like our program is focused on education. You know, we’re not proposing that we can go out and scoop a bunch of plastic and make a beautiful product, like mechanically and physically. And like your, your doubt is like true. Like that idea that you can convert

handful of mixed plastic on a beach to a physical product that you can rely on and trust for decades is a lot of that is fiction. The reality is that they need to process that so much to get to one specific type of plastic that they can extract value from. So, I think as far as where we should be focused on, focused on solutions as to why the material is winding up in the ocean or our environment and cutting off the material, the source, and we’re using that waste.

is a part of the solution and we should absolutely be focused on that. Cleanup as well, as long as we’re not diverting too much attention from tackling that problem. But then there’s an overconsumption issue in there too. There’s just products, especially single use products that should never be built with plastic in the first place. If you can build a skateboard that lasts years or a jacket that’s 20 or 30 years, why should you be putting that same material into a package that someone uses for five minutes and then it’s gone? That you’re under.

you’re mismatching the life of that product with it. And I think that we’re trying to still, as an ecosystem, as an industry, figure out what our relationship with plastic is. Because I think there is a role there. I think that as a society, we’ve just put too much attention on that. And that’s led to this problem where we’re pumping out more and more new plastic every year. Even though you hear about all these recycling projects and cleanup efforts, the plastics industry has been growing. It’s not like…

Adam (21:14.11)

you

David Stover (21:14.262)

It’s not like they were producing 300 tons of new plastic two years ago. And they’re projecting to like have that in the next couple of years. Like they’re still growing their use of new plastic. And so I think that, um, you gotta be careful in like finding the winds and championing them, like, and not getting too disenchanted that like, we’re not making a difference and we’ve battled with that before, but also being realistic and, and calling out like, okay, well, this is what’s not working and like.

Yeah, it’s great to recycle, but we can’t just look at recycling a small percentage of the overall pollution and think that we’ve solved the problem now. You know, we got to be level-headed about that.

Adam (21:53.754)

So you kind of jumped into one of these questions I was going to get to later in the podcast, but it’s such a good tee up here. How are we doing with respect to the ocean plastic problem? Because I think like, like I said, it’s top of mind. I think people feel good about buying a shirt that’s made out of, you know, 18 recycled plastic bottles. But on the whole, how are we doing with the ocean plastic problem?

David Stover (22:22.158)

That’s a good question. I think that in the last 10 years, certainly, the awareness and the amount of funding and research and implementation and even kind of physical programs has improved. But I’d say that there’s a lot of work to be done. If you look at the estimates for the amount of plastic pollution going to the ocean every year, I think that we’ve only made a dent so far. I think that we’re starting to give people

And this is obviously complicated because we’re involving regulations for countries and industries, like how they’re using plastic and what are the end of life responsibilities there. I think that will have a huge impact and I’ll stick to apparel because we’ve been working a lot in apparel, but the apparel industry right now is like 35 regulations that are drafted or going into law that are like actually companies and industries working on like.

how are we regulating the amount of waste coming from this industry? And I think as you see those policies and laws come online, that’s going to be across industries that will make a huge impact on to like just the amount of waste that we’re producing. And certainly like recycling is component of it. So there’s been a lot of growth and recycling infrastructure. So equipment collections. I think there’s been a lot of positive movements in that in the last couple years that will have an impact. And then just.

the production side of things. I think that like, I’m hoping in the next five to 10 years that people will really target and understand that like, we have to stop making as much new plastic as we’ve been making every year in order to really start winning that battle. And from a volume perspective, I think that like, we’ll start to see bigger wins once that happens. Once these producers of new plastic are really focusing their…

investments in facilities and equipment on like producing just regenerative materials or alternative materials and really getting them away from producing new plastics.

Adam (24:23.266)

You referenced earlier, um, organizations and certifications to, to validate traceability, transparency, accountability. I’m curious, what would you advise somebody who, you know, has that, you know, this was made with recycled plastic. What would you advise as to how they can better navigate and what they should look for to know that they’re making the best.

purchase choice they can.

David Stover (24:54.542)

It’s a good question. I would, well, I’ll say two things. I don’t think it can all be on the consumer. I think the consumer is trusting the brand to make the right decisions. And we were fortunate to work with some great brands. But I think the brand on behalf of the consumer needs to stand behind those claims. And if they say something’s organic or recycled, I think it’s the brand’s due diligence to go to that.

facility, go to that location, actually see what they’re collecting and processing and recycling. You know, we work on, there are certifications like audit certifications, global recycled standard or recycled claim standard. There’s a long list of these claims that, you know, you can go and get an audit done and we do it and they come and see you physically a couple of times a year. But in order to have confidence and trust in, you know, a material or story or source of it.

all the responsible brands are going to those locations. They’re going to the factory to watch how the products are made. They wanna see their records of where the materials are sourced from. I think the consumer needs to back brands that they can trust that are doing that. And the brands being more transparent with them and being like, yeah, this isn’t, I’m not just gonna put recycler on the label. I’m gonna tell you exactly where this material came from and what it is. And if you’re a consumer and a brand is not doing that, like if it’s not obvious when you go to the website,

about where that recycled material came from or what type of plastic is, then I think it’s rightful to be skeptical of that because we’ve seen it for decades and certainly in the recent times that, yeah, I think it was mentioned before when something becomes marketable, everyone wants to put it on their label or everyone wants to talk about it, which is great, but there’s also a downside to that, that you may be pushing forward solutions that are hard to verify.

Adam (26:19.398)

Hmm.

Adam (26:45.946)

Feels like the little guy never gets a break. Never get a break. Never get a break. Gotta wash the recycling, find out recycling, you know my curbside recycling, who knows how much goes into the trash. It just feels like I want to be an optimist. I really want to be an optimist. I really do. It’s just tough because it becomes hard to wade through all the marketing. It becomes really difficult to kind of sift through all that. I’m curious, are you

David Stover (26:48.394)

Hahaha

David Stover (27:12.446)

And I think that like, yeah, go ahead.

Adam (27:15.662)

Well, I was going to switch topics, but please wrap up that thought.

David Stover (27:17.406)

Yeah. No, I was just going to say that I think that we’re going to see a lot more transparency from brands where they’re going to have to detail out like, you know, what is the reduction in emissions like you mentioned before, like what are the impacts of all of this, these processes and like you want to be able to show that like, you know, I want to feel good about buying this hat or that jacket and I want to understand like, why is it better than the alternative? And I think, I think the, at least in the apparel and the outdoor space, I think they’ve already got

better and they’re going to keep getting better at quantifying that, measuring it, using technology to trace it and really let the consumer make the decision based on a more even playing field.

Adam (27:58.79)

At some point, do you foresee going beyond fishing nets and tackling other culprits?

David Stover (28:07.266)

You know, in the beginning, we always talked about that. It was like, you know, we’ll do fishing nets and, uh, you know, people always ask, what are you going to do when you run out of nets? But, um, the more that we’ve learned about it and the more places we’ve gone. Um, you know, I mentioned 1600 tons last year, that figure of like 80 containers. Um, you know, based on independent surveys that we followed in studies of the fishing industry. Like, I mean, they’re using somewhere between 500,000 and a million tons of new gear a year. So every year they’re.

This is gear that’s going in to replace nets, to repair nets. And so they have a lot of waste accumulating on an annual basis. And so for now, because we’ve developed know-how in how to develop relationships with fisheries, get them on board with our solution, we’re designing shredders to be able to process the material and special washing lines and cutting devices. And the transportation that we work on is all based on moving nets.

And so like for this foreseeable future for us, like we’re not, we’re not looking at any other material from a waste percentage, we are really interested in obviously end of life of the products we’re making. That’s something that we’re interested in, um, on an ongoing basis of like beyond the nets, how do we participate in making sure that there’s a responsible end of life for the products that the nets are going into, and that’s something in the future that we’re interested in exploring.

Adam (29:34.166)

Um, do you communicate with, or are there any coalitions, uh, with other organizations or nonprofits that are actively like in ocean cleanups, right? That are, that do have boats on the water that are trying to collect, collect all that, or do you have to stay siloed in exactly what you’re doing?

David Stover (29:54.678)

Yeah, I mean, Ben and our team sits on a panel, it’s called the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. And it’s under OSHA Conservancy right now, but it’s a number of nonprofits in this space. And like within that group, you know, there’s divers, there’s cleanup efforts at ports, there’s other net collection efforts, there’s fisheries, it’s kind of like across industries. And so like I’ve personally been out on the boats a couple of times with the tech divers to get the gear.

We support and like are all about that mission, but for us, like our sole business is set up to like educate fisheries Tell them what’s happening to the waste Certainly, we use those examples of like hey if these nets are cut off or thrown like this This is what happens to it. It sinks gets entangled in reefs. It becomes a floating raft We’ve been a part of some of those issues to help bring that gear back or to prevent it in the first place but our whole like supply chain is based on like

we’re gonna manage the infrastructure and logistics on land to collect that back. And certainly I think that the diving and the rescue efforts are important, but really that needs really big donation, philanthropic dollars to support it. I think it becomes kind of like a sister, brother exercise as opposed to like a combined effort.

Adam (31:18.714)

Are your where are you collecting the nets from?

David Stover (31:22.794)

Yeah, so we work now in more than 40 communities. We started in Chile. The government there gave us initially like a small government fund. That’s how we got started before the Patagonia investment. And so we walk work across the coast of Chile. Now we have two facilities there where we aggregate material from Chile. We started working in Peru and Argentina, which makes sense. They’re neighboring.

We take a small amount of gear from Argentina, relatively small fishery. We’ve been expanding a lot in Peru. And then the last couple of years, we’ve also moved up to Ecuador. Ecuador has a lot of major fisheries there that we pull gear from. And then in the last year and a half, we have been collecting in the US. So I’m sitting at a facility here in Oxnard. We’ve been taking gear from the Pacific Northwest, California, the Gulf. We are looking in New England as well.

Adam (32:07.218)

Hmm.

David Stover (32:16.77)

kind of aggregating waste. So North America is a focus. We have a small facility in Ensenada that’s been collecting that’s in Mexico for about the last year. That’s supported by certainly some grants here in the US. And then we just opened a hub with a partner in Japan this year. So we are looking at kind of the broader Pacific region to set collection points as well.

Adam (32:40.518)

What have been the major challenges to getting this done, whether it’s on the collection side or the end material side, what were the challenges that you encountered?

David Stover (32:52.406)

I mean, I’d say we still have challenges on a weekly basis, but I think that it’s dynamic and interesting because we get to work across the supply chain from the source of collecting the waste to getting the end-final product. And so I’d say you have, obviously you have interesting challenges throughout that, but some of the major ones for us, handling waste and processing waste.

Adam (32:54.967)

Huh.

David Stover (33:18.482)

and moving it from the places that we collected, like physically moving it, like on a boat or on a truck, the permits you have to have in place, the conditions that you have to think about when you’re receiving that material. That has certainly been challenges that we’ve had to overcome and build this. We’ve learned a lot about the laws around where you can ship waste and what form it has to be in. That was certainly been a huge challenge. And then I think just like getting it into a product. I mentioned that before.

And, you know, it’s beautiful to think about someone going out with a vacuum cleaner and scooping hundreds of different compounds of plastic with different colors and different contaminants. But the reality is that like, if you’re going to go out and buy a ski jacket and you want it to last for 10 or 15 years and you want it to be waterproof and you want it to be really high quality, like the material that’s going into that. It needs to be really high quality. It needs to be free of contaminants. It needs to be really consistent.

And so yeah, a lot of lessons learned on the way that we clean the material, the way that we have to separate it and ensure that it’s like really consistent. Um, to the point where like we’ve gotten, we’ve learned a lot in doing that for fishing as you mentioned the recycled bin before and like, where does that go? Like to me looking at like a recycling bin with mixed plastic is like a nightmare to think about like how that will go into a quality product because there’s so many different types of plastics and contaminants and films and inks.

that like, you know, I think for us, like we’ve definitely learned that like really having to focus on one type of material and be really good at like how you’re going to move that from the, from the part of it being a waste to going into a product. So yeah, that is, that is a major challenge in the recycling world.

Adam (35:04.094)

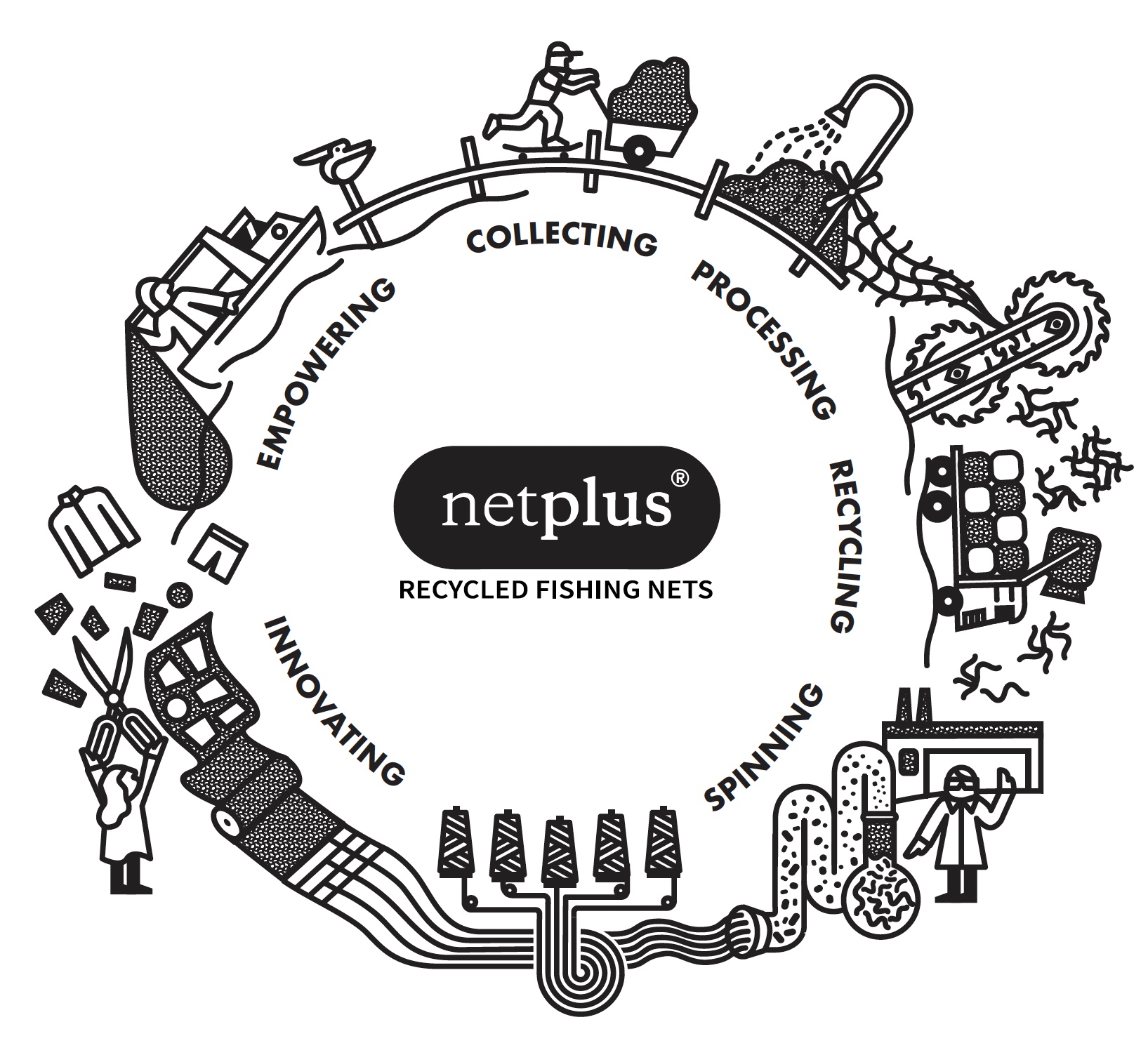

So the product in question is net plus. And you partner with a staggering number of prominent brands and you mentioned Patagonia, but I’m on your website now. It’s Yeti. It’s Coast of Sunglasses. It’s Trek. It’s Rivian. How is, what is net plus? How is it this dynamic and what are some of the products that consumers would see and be like, Oh wow. Yeah. I heard that guy on the podcast. That’s where that came from.

David Stover (35:34.25)

Yeah, I mean, I think in this transformation from like us designing our own products and like certainly we launched products under the BUREO name in the beginning. And like one of the lessons learned from that was like I mentioned before, like people were really on board with this mission. Like they wanted to know that there was a solution for Nets and they wanted to be a part of that. And so by learning that like that was our success and like our purpose really in life and for our careers.

Like then the goal became, okay, how are we delivering that solution? Like, how are we delivering this material to the market? And kind of growing up under Patagonia, like we really became like an ingredient brand. So an ingredient brand being net plus stands for like a responsible source of alternative feedstock. And for us, it’s only recycled fishy nets. And so the idea is that ingredient brand can plug in and be a solution for quality brands that are building products right now.

And like our biggest wins are, you know, plugging that plus into a product that uses like Virgin plastic or like new plastic, because there’s environmental impact associated with that. When you make, you know, a jacket from Virgin plastic, you have to process that material to get it into the form. And there’s a lot of energy. There’s a lot of impact in the environment that comes in play. And so net plus is really like our purpose is to replace those, those higher energy or higher impact materials.

with net plus and like Patagonia certainly launching that we did hats and shorts and jackets and like, you know, they’ve been a tremendous partner growing from one product to over 200 products in like a 12 month cycle. And like they have said this to us, which has been like a really big challenge for us and going to market is like, we’re never going to be successful. Patagonia is the only one that does this. And like as a supporter of us.

Adam (37:20.167)

Hmm.

David Stover (37:22.194)

it’s been a great challenge to think about, okay, we need to take the solution and not just think about being successful at this 80 containers of fishing nets a year, but like, you know, how do we get this to 800 containers a year and put that into, you know, hat brims and apparel and eventually like industrial applications. And so a lot of the partners that we’re working with now, I’d say are more like capsule projects. Um, coast has been a longstanding partner where like it started with one

many frames across their line that include net plus material, recycled fishing nets. Rivian started putting it into the hat brims and the hats that the employees wear and that they sell. And certainly we have ambitions to go beyond that with them and really target the industry in a way that we’re providing a solution for them. We’re helping them switch from maybe more impactful materials to kind of lower impact materials. And that’s…

Honestly, like when we think about kind of the long-term vision for the company, like we are still focused. Our mission is to end fishing net pollution. Like we want to be a part of the, uh, the, the community and the group working to keep plastic out of the ocean. Like that gets us up every day. Like that’s why we get excited to open new facilities and hire people. But like, honestly, at this point, I think our bigger impact in the long run could be just uncoupling companies from using.

new plastic or virgin plastic and getting kind of supporting that economy where they’re looking at, there’s got to be an alternative way to do this. Like I want to source materials differently. Like I want to educate consumers about this. And like I think that could be our bigger impact in the long run.

Adam (39:04.703)

It’s kind of a weird question, but then is your goal to one day be out of business because you’ve successfully ended fishing net pollution or do you take everything you’ve learned and done and you just pick it up and you find, like we talked about earlier, do you find another raw material that you guys can start focusing on?

David Stover (39:26.454)

Yeah, good question. I mean, early on, we used to joke and say, like, people would say, what are you going to do when you run out of nets? And we’re like, well, I guess we can just, you know, be happy we accomplished something and just throw a party. But, you know, realistically, everything we’ve learned about that industry is that, you know, as long as we’re consuming on an annual basis, there’s always going to be waste. But yeah, I think that we are thinking into the future. I mentioned, like end of life products, like we’re interested in where the material goes that we’re collecting.

Adam (39:34.282)

Yeah.

David Stover (39:54.702)

Uh, and I’m certainly conscious that like, you know, the fishing industry has been challenged. Like there is potential there. There will be decline in certain fisheries. And so that will certainly be a part of it. Um, but given the scale of the problem they have right now, um, you know, that unfortunately there’s too much material even for us to handle, like we’re dropping the bucket still in that space, but yeah, going forward, I think hopefully I’d say more inspiring people to come up with solutions for other materials, like I don’t see us.

Adam (40:22.17)

Hmm.

David Stover (40:24.066)

coming on and adding 10 to 15 more feedstocks to handle. But if our model and the industry’s adoption of that inspires people to target climbing rope or ag waste or something from planes or other, anything that you can dream up, I think that that’s what we see is happening is people kind of building up these parallel solutions that are kind of compiled together.

Adam (40:52.094)

Part of the impetus for this particular episode was news that you had secured a round of funding. And I’m curious, what does that mean practically? What is that going to help you do and what happens now that you have that funding secured?

David Stover (41:05.194)

Yeah, I mean, like, for real has been lean since day one. I mean, we, we were, you know, really resourceful and, um, keeping our costs and overhead low to build this and, you know, Patagonia being a great support for us from the beginning and helping us kind of scale this the last couple of years, um, this year was what we saw as an opportunity that, okay, we went from 10 tons to 1600 tons and that took 10 years basically, which is great. Like we were able to grow.

But like, if we’re going to have a real impact here, like we can’t wait another 10 years to add another thousand tons to our ability to recycle. And so like, I think that that’s when we looked at the players in the industry and who is supporting this, who is interested in recycled materials. We’re working with Toyota Susho, who’s a part of the Toyota group, obviously a large multinational company.

that recognizes that they want to support recycled materials. And so for us, what that means is like, we’re just looking at expanding our mission, opening more facilities, hiring more people, purchasing more equipment and like scale on our side, unlike a lot of, I’d say companies that are looking at how many customers are they adding.

You know, how quickly are their sales and KPIs growing? Like we’re certainly interested in that, but like the immediate impact under printing all of it is like how fast can we grow the supply chain? Like how fast can we increase our collections? And we really see this fundraise as a way to do that and really bring our solution more broadly to the apparel industry. I mentioned before that, you know, Patagonia has been an incredible partner and backer of this and like, I think they’re behind us and that we want to bring this.

to the industry at scale and be able to be a real solution. We don’t wanna show up at a company and say, we can help you, but only this little amount. It’s like, we wanna be able to be like, we can deliver this and grow it with you and actually make a difference when it comes to waste in our environment, when it comes to their impact of their products and really go towards being responsible on both those fronts.

Adam (43:14.422)

Another weird question for you. Do you think this is the last job you’ll ever have?

David Stover (43:19.842)

That’s a good question. We talk about that actually, you know, now that we’re like in year 11. You know, I think we definitely take it on our whole team, like even the team members that we’re adding, like it’s kind of brought together by being mission-purposed. And I think for us, like we see this as our legacy. And so I think that like certainly there’s a lot left on the table right now. And like none of us are thinking about what’s next. We’re just, how do we scale this to a point?

where it can run. And certainly I think that the model underpinning Vareo and the idea behind Net Plus, I certainly think is going to live on for a very long time. I hope to be a part of that. But this idea that we’ll need to collect waste efficiently in the future and replace materials with alternatives, I think is not going away. I think there’s going to be a lot more focus on that. And so I certainly see myself working.

towards this mission and towards our mission for the foreseeable future.

Adam (44:22.014)

a little bit about how the sausage is made on the on the podcast here. I have a crib sheet, right? So I get I get these questions, I review it, I get a good idea how I want the podcast to go. And then while the podcast is going, Luke sometimes furiously starts typing, and it’s like a new question. And this was happening. So I got to ask this question. What? And it’s a good one. It’s a good one. What are the current products that Braille or net plus is involved in? And and how has that evolved?

David Stover (44:36.139)

Nice.

David Stover (44:50.282)

Yeah, great question. I mean, in the beginning, you know, we were, we were mechanically recycling. So layman’s terms, like we were melting down the material in a pretty rude form and putting it into a steel bowl. So like, the way that you make waffles for anyone that makes waffles in the morning, very simple, the way that we were making skateboards, you know, you were breaking down the material in a way that could be melted into a mold and outcomes of skateboard. And then eventually that

Obviously we, we increased the quality of that, started working with Carver on skateboards, Futures is making surfboards now in California, sunglasses. Those are great partnerships and ones that will continue. But in going after kind of the apparel space, the main like R&D development there has kind of been working on advanced recycling underneath Patagonia supply chain, and this is like to the point where we can take, um,

nets through our supply chain and get into like a super fine thread for the outdoor space. So think like the lightest insulated jacket you could make. To do that, the thread going into that, the nylon thread, it’s favorable because it’s lightweight. You know, from a packing perspective, waterproof certainly is a requirement for a lot of the materials that we work on, breathable. And I think that like, because of that shift,

we’ve been focused a lot more on apparel because nylon in general, for its property, the same reason why people use it for fishing nets. It’s light, strong, they can rely on it. That’s why it’s used in a lot of performance applications. So think of board shorts, waterproof jackets, insulated jackets, climbing gear, ski gear, kind of ubiquitous across the outdoor industry. And so for us, we’ve really looked at that space and

this isn’t just us, but there’s research of looking at this, like 98% of those materials for all nylon textiles is just virgin new material. So, Adam, you mentioned bottles a couple of times. Bottles is PET, so different type of material, polyester, but for nylon, still 98% of the world is living in the virgin place. And so we see this as an opportunity to connect this waste with this problem that really kind of the apparel industry has.

Adam (46:52.734)

Jeez. Oh man.

Adam (47:12.434)

Are companies coming to you and saying, hey, we would really love this to be made, or is it more that you have brainstorming sessions and you’re like, hey, what else can we do with this?

David Stover (47:25.598)

Yeah, good question. We still try to do that because it’s fun. Like the brainstorming and giving people ideas. Like we enjoy that. Like I think there will always be an element of like being a part of design and saying like, you know, wouldn’t it be great if we could go after this product? But kind of where we’re at now and the relationship is like, typically, if we have a conversation with a brand, it’s understanding like where are you using or where do you need to use

Adam (47:30.608)

Yeah.

David Stover (47:54.478)

Do you have like high alpine gear that you’re using nylon and like, we’d love to like swap that over. Like if it’s virgin or if it’s not traceable, if there’s some properties of that. And the partners that we’re working with, the mill partners that we have that make this fabric and certainly the brands, that’s the level of conversation. Like the easiest thing is like, we’re not trying to, we don’t have to recreate the mold, design our own products and then try to sell those to them. It’s that, hey, you guys, this is…

known material with known properties, we have a more responsible way of sourcing that and creating that and we’d love to integrate that into your supply chain. And I think that we’ll be on that path for quite some time in the future. I mean, we’ve worked with some really talented product designers and a lot of people have a lot of ideas. So I think there’ll always be an opportunity in the future to make something interesting from the material.

Adam (48:46.266)

have those conversations why would a brand ever say no is it is it is it ever cost prohibitive is there how do those conversations play out

David Stover (48:55.206)

Yeah, good question. I mean, certainly that it’s cost prohibitive. We need a longer podcast to talk about why virgin plastic are so cheap. But yeah, just the, we had a long conversation this week with a research group on that, that inevitably the cost to collect, transport, and then process the material right now is just still quite a bit higher than if you just bought it new. And so I think that a lot of the brands that we talk to, they have commitments.

Adam (49:04.308)

Yeah.

David Stover (49:24.01)

they’re making internal commitments to get to these conversions. It just takes time. You know, like thinking about like designer of a product, they have to, they’re used to like a fabric and they have to integrate a new fabric and then test it. And there’s just a lot of complexities in that. Some of which are out of our control, obviously. But I think cost is definitely a barrier on the growth of the recycled programs across the board. And then just like I mentioned before, but you know,

typically we just want to go after products where the material makes sense. Um, and for some brands, it doesn’t make sense. Like they, they may not need recycled nylon or it may not be in their line. Um, and so that that’s okay if they’re able to use other material. But, um, yeah, I think that in general, like if we’re able to get the right people in the room from what we found, um, and certainly the designers are a big part of that, and if they’re on board with the mission, then it can be pretty plug and play, um, and that’s.

kind of our job is to like lower the barriers and make it easier for brands to adopt.

Adam (50:28.914)

You talked about how the material has evolved and the capabilities have grown over the last decade. Is there like a unicorn product that maybe it’s not there yet? Maybe it’s not quite, you’re not, you don’t quite have the capacity to nail that product, but someday if you could, you’d be like, this should be made of recycled fishing net.

David Stover (50:50.61)

Yeah, great question. I’d love to drive an EV vehicle that’s built mostly from fishing nets. I think it’s possible. You know, like you start thinking about like industrial scale applications and like certainly like lightweight vehicles is one of them where like cost perspective right now, volume like that industry uses way too much material for us to keep up. But long term, like you know to have an impact.

Like we have a lot of runway right now in the apparel space and we’re gonna focus on that. But like, you know, thinking about like reducing the weight of products that don’t need to be as heavy as they are and like really going after like big consumption uses the material you get into the industrial space and certainly vehicles comes front of mind to that. Maybe a spaceship, maybe like a, like a low flying hovercraft that we’ve been hearing about for years is gonna take over the future.

Adam (51:45.062)

All right, so I mentioned I try really hard, try really hard to be an optimist. And I wanna close out this podcast. Give everyone a reason to be optimistic about where we’re at with ocean pollution and plastic pollution.

David Stover (52:01.93)

Yeah, I mean, I think that when it’s only doom and gloom, it’s like really hard to like see like what the difference you can make is. But like, I think like I’ve been fortunate enough to see it like in smaller components. I think like I still surf on a regular basis and like those moments where you’re like in the ocean and you’re able to kind of like take a deep breath and know that like, yeah, there’s all of these challenges that we have.

Obviously we’re starting to see a lot more of them just in kind of the impact on the planet. But there’s like an incredible group of people working on this. And like whenever we talk to schools and certainly younger generations and you hear stories from kids that are like going home and teaching their parents about solutions they learn, like I’m putting, I don’t mean to pass the buck off to the younger generations, but you know, when you look at like kids in high school now or elementary school, I just think that like we were the start of like trying to understand what was happening in the planet.

I see that generation taking it personal and really making it on them to want to protect it. That gives me hope that we’re inspiring the next generation to really be responsible and things that we’re trying to hold companies accountable for, hold politicians accountable for now. I’m hoping that generation replaces what we’re trying to do with status quo. Protecting lands will be like, yeah.

we should have always been doing that. Access to clean water, yes. Like pollution, yeah. We should have never been dumping material anywhere. That’s crazy that we were just able to like throw things in a landfill and bury it or throw things in the ocean. And so that gives me hope, you know, knowing that they’re seeing everything that’s going on and they’re taking it personal and you know, really are the stewards of the planet going forward.

Adam (53:53.118)

The company is Bureo, the website is Bureo.co, B-U-R-E-O, if you wanna find out more about where Net Plus is used and how you can help. My guest is David Stover. David, that was awesome, thank you so much.

David Stover (54:06.35)

Thanks, Adam. Thanks, Luke.

Adam (54:08.39)

That thank you, Luke. That is the gear junkie podcast and we are out. Nice job, man.

David Stover (54:17.81)

Yeah. Sorry, I pulled back the curtain on you at the end, Luke.

Adam (54:26.902)

I want Luke to have a microphone front and center. Yes, do it. We need the banter.

David Stover (54:29.906)

Yeah. Good questions. Yeah.

David Stover (54:43.694)

So I grew up on Block Island. It’s like off of Rhode Island, kind of out in the ocean there. Nice. Nice, yeah, I go back every year. Like I love Rhode Island, that like little part of the world. But I’ve been living in… Yeah, yep, I grew up there. I mean, I…

David Stover (55:10.222)

Green Hill was my spot when I spent time in on the mainland as we call it there.

David Stover (55:17.57)

Yeah.

David Stover (55:40.846)

Gross.

Adam (55:43.487)

Ha ha

David Stover (55:47.916)

Yeah.

David Stover (55:59.31)

I mean, the ocean community is amazing. I honestly think that part of what you just said, that’s the reason why people are so passionate about it. I said it before, but when you have to think about immersing yourself, literally underwater, the diving community is the same way. I think they’re so passionate about issues because you’re coming face to face with it. Surfing, people are getting sick. We’re friends with a bunch of the people that started Surfers Against Sewage in the UK. Their whole thing was like…

You know, there’s sewage running into the water. Like as a surfer, of course, you’re going to be the first one that’s against that. Cause you’re like, you’re in the water no matter what, if it’s cold, if it’s not, it’s not like a sunny day, you’re going to surf. It’s like every day you want to be in the water and like the day that you can’t, you’re going to be pissed off and like just mad that someone’s able to dump stuff into a place that you value. And like, I think the ocean community has been

like a really strong voice for this issue because like no one wants to see a photo of a beach with plastic on it or like water with or a turtle with something around its, you know, nose or anything. But like when you’re in the water as a swimmer, surfer, diver, anything like it’s just like you take it personal. You’re like you’re like you’re harming me, you know.

David Stover (57:29.078)

That’s cool.

Adam (57:30.235)

There’s a gnarly group of folks that surf Lake Superior in winter, and I’ve always wanted to go up there and see it.

David Stover (57:34.7)

Yeah.

I haven’t seen it either, but I’ve met some of those people and I’ve been invited and I’m like, mm, I grew up in New England and surfing in the winter time and wearing a six, five, four and seven millimeter booties and hoods and five millimeter gloves and you can barely move. And yeah, a cold day in Ventura where I’m at is you got a four, three on. I think that that’s about my limit now.

Adam (58:01.66)

Mm-hmm.

David Stover (58:03.373)

You soften up.

David Stover (58:09.463)

Yeah.

Tomorrow morning, I’ll go tomorrow morning. Yeah, I’m like, I try to avoid the day it’s raining, but usually after a day or two, I test the limits a little bit. I haven’t actually knock on wood gotten sick in a while. I did live in LA for a while and got sick pretty regularly, ear infections and other sort of crap. But.

Adam (58:30.458)

Wait, what’s the what’s the science there you get sick when it rains or what’s the deal?

David Stover (58:36.947)

Yeah, it’s, I mean, I didn’t, I never knew about that in Rhode Island. Like, I mean, when it rained, like we didn’t, you didn’t have any worries, but here, like especially in LA where you have like a concentration of people. I mean, it’s multi-pronged. Like the biggest thing you got to worry about is like septic and you get a lot of runoff from septic fields and even like, even the industrial septic.

processing plants tend to like overflow when it rains and run into the ocean. So that’s number one, like you’re talking about like gnarly bacteria, but even like stuff coming off roadways, like the amount of oil that gets built up in California because it never rains. And then when it rains, all of that gets flushed out. So you got a bunch of like, you know, chemicals running down the storm drains. And then up here in Ventura, we got ag fields. So whatever the hell they’re putting on.

strawberries in Oxnard County and citrus fields is like that’s flowing into the ocean. So you get like a bit of a concoction by the rivers and harbors here.

Adam (59:39.05)

I thought the YMCA pool was bad. And it is bad. It’s definitely bad. But that sounds real gnarly.

David Stover (59:45.188)

Yeah.

David Stover (01:00:27.534)

It’s like, go take a shower. Go wash up.

Adam (01:00:27.601)

Ugh.

David Stover (01:00:37.238)

Yeah, I mean, usually the worst is usually like, yeah, you can get like a chest infection or like an ear infection. I’ve gotten staff where I’ve had a cut and been surfing and gotten staff. Like I think that would be like the number. I think you hear crazy stories about like amoebas and other sort of wild stuff. I’ve never obviously experienced that or known anyone, but yeah, it’s just, you know you can get sick if you go into dirty water. It’s kind of just like a known risk.

Unfortunately.

David Stover (01:01:13.034)

Yeah.

David Stover (01:01:24.078)

Cool. Yeah.

David Stover (01:01:53.938)

Awesome. Thanks, Luke. Thanks, Adam. Enjoy the combo.

Adam (01:01:57.887)

Awesome. Thanks David. Great app.

David Stover (01:02:00.202)

Yep. Have a good weekend. See you guys. Bye.

Adam (01:02:06.562)

I will have an intro for you in the next hour.