Beyond Salsa and Surly, at least a dozen additional bike companies now sell frames or complete-build fatties. Chain Reactions Cycle, a bike shop based in Anchorage, Alaska, sells fat bikes branded 9:ZERO:7. Moots, a high-end builder in Colorado, sells its fat FrosTi model, which we previewed last fall.

Icycle Bicycles was an Anchorage builder. Hanebrink has a line with small fat tires. Fatback is another Alaska brand. Oregon’s DeSalvo Custom has made snow-bike frames off and on for years. Or try Schlick Cycles, A-Train, Twenty2 Cycles, and Sandman of Belgium, to name a few. There are more out there, too.

Indeed, the category has expanded significantly in the past couple years, including brands that have come and gone. A builder named Ray Molina made production wide rims, which were used on some of the original snow bikes. I rode a fatty from Minnesota’s Evingson Cycles in 2006, a company that dissolved. Wildfire Designs Bicycles, one of the Alaskan originals, is no longer around.

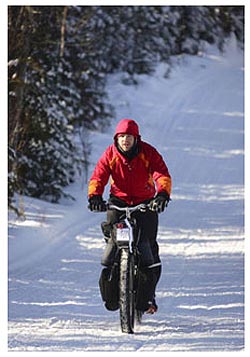

Fat bikes are often custom jobs, though Salsa and Surly sell complete-build bikes. Costs are $1,500 to $5,000 or even more, depending on frame type and components. (Salsa’s Mukluk 3 starts at $1,600 complete) They are heavy, 35 to 40 pounds on average, and much slower than mountain bikes on regular terrain.

On the snow, fat-tire bikes are usually a good choice, though the big rubber is no panacea. Here below is my text from 2006, when I trained on an Evingson bike and demo’d the original Pugsley before rolling to the starting line at the Arrowhead 135 race. In the event, despite a navigational error that cost me four or five hours (ouch!), I took 9th place on a fatty. Here was my opinion after the race. . .

My experience with these bikes has been mixed. Though the fat tires do provide some float in sand and snow, they are heavy and noticeably harder to pedal. In conditions where a regular mountain bike will not work — like loose beach sand or a blanket of 4 to 6 inches of snow — a [fat bike] can excel. But in many situations I found them to offer no advantage.

During the Arrowhead 135 Ultramarathon, which took place on a snowmobile trail with sections of hard pack as well as soft snow, nearly half the cyclists rode [fat] bikes. But the winner, who beat the closest competitor by more than four hours, rode a mountain bike with 2.5-inch tires. The second and third place finishers rode fat bikes.

I took 9th place in the event riding a bike made by Evingson Cycle. It was equipped with custom racks to stow my 15 pounds of food, water and winter camping gear. The weight was evenly distributed on the bike and it rolled along smoothly for hours on end. But for most of the race the large tires were superfluous, and indeed in those conditions I found them to be more work to pedal than they were worth.

All the above said, the bikes have evolved since 2006. They are more efficient and a bit lighter, but they are still pigs. Fat bikes have their place, but I think the recent buzz around the genre is a bit loud.

In January, we published a thorough review of the Salsa Mukluk Ti. Our editor, T.C. Worley, rode the bike mostly on dry trails, not snow, and he noted the rolling resistance was “very substantial and the steering slow and dull.” He continued, “Off the road and onto trails, the sluggish and oafish behavior dissipates as the Mukluk barrels down the dirt with purpose and force.”

Worley noted that on dirt trails with the Mukluk logs, roots, and big ruts are “no match for the inertia and mass of this bike.” Its overall weight, he noted, is great for momentum, but that the girth is “very noticeable” on hills.

Fat bikes seem to be popping up everywhere. We see lots of people comutting on them in Minnesota, and the bikes are truly fun. (Wrote Worley, “Pedal-powered monster truck? Yep, that’s the analogy here no doubt.”) Almost every rider in the Arrowhead 135 and similar snow races now ride on fat rubber. One of our writers raced in Vail last month during the Teva Games on a Surly Moonlander model during a unique event called the On-Snow Crit. While about half the pack in that race rode fatties, the winner of the crit, it should be noted, was on a normal mountain bike.

But in snow, on sand, or for some serious grip on dirt or rocky terrain, nothing else made compares to a fatty. The bikes have spurred a small revolution of biking on snow for long distances. As a micro-niche, there are a few explorer types riding all-out wilderness like long, uncharted beach stretches in Alaska. Some combine pack rafts with the fat bikes for locomotion over water and land. (We covered one man who has a Kickstarter campaign going to fund just such a trip.)

If nothing else, the fat bike category has fused some significant energy and creativity into the bike world. Try and get on a fatty this year if you can. Who knows, you might never want to ride skinny again.

—Stephen Regenold is editor of GearJunkie.com. Connect with Regenold at Facebook.com/TheGearJunkie or on Twitter via @TheGearJunkie.