Sharkbanz has steadily improved its shark deterrent products since 2014, and the surfing world appears to be accepting the brand’s contribution to the sport. With FCS, the legendary fin and hard goods company, collaborating with Sharkbanz to create the surf-specific POD, major industry players have come to acknowledge Sharkbanz’s value.

Professional surfers have taken note as well. Jacob Willcox, the hard-charging goofy-footer currently competing on the WSL’s Championship Tour, credits Sharkbanz with giving him peace of mind while surfing sharky, remote waters in Western Australia. And with rumors circulating about a partnership with one of the most famous surfers of all time — and let’s just say, an apt partner for Sharkbanz — the company’s credibility continues to rise.

Surf culture has proven to be highly selective about the technology it chooses to embrace. Surfing is already such a transcendental experience that few people are in a hurry to overcomplicate it with gadgets and gizmos. For Sharkbanz to have a chance, the brand knew it had to be sensitive to the core values of the sport. That’s why Sharkbanz co-founder Nathan Garrison made it a priority from the outset to create a device that is simple, affordable, and doesn’t hamper performance.

Sharkbanz Levels Up Its Progression

Sharkbanz made huge strides in shark deterrent technology with its first offering, the Sharkbanz I, and fine-tuned it with the Sharkbanz II, but the brand was determined to take it to the next level with the help of FCS. Who better to help them create a high-quality, surf-specific shark deterrent than a company that forged its reputation over 3 decades of creating reliable fins and other surf products?

Garrison invited me on a surf trip to demo the product. As we prepared the boat — the Dos Lunas — for launch, he handed me the POD. The first detail I noticed was its compactness. At 2 ounces and around the size of a bottle cap, it’s simple, sleek, and unobtrusive.

As I examined the two holes in the POD, Garrison explained that these were included to allow it to be conveniently fastened to surf attire. By way of example, he looped the POD to the elastic cord in his baggies’ pocket. The POD also fits nicely into wetsuit pockets.

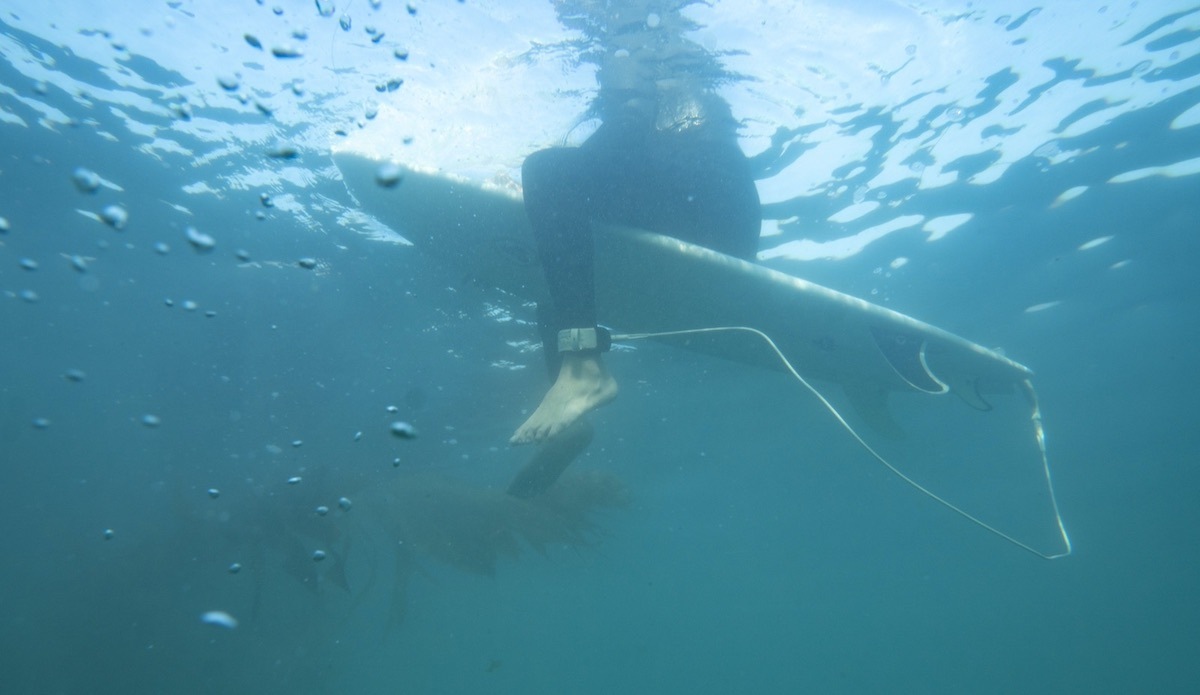

During the developmental phase, FCS and Sharkbanz decided that they needed even more convenience. Despite its diminutive size, they knew some surfers would view it as a distraction to performance, so they decided to include a neoprene sleeve with ends that secure together with Velcro. Surfers can slip the POD into the sleeve and then use the Velcro to attach it around their leash cuff.

Once attached, you forget it is there, as I found out later. Another facet I like is that, assuming you use the same leash, you don’t have to worry about attaching the POD for every session. One of my favorite things about surfing is the simplicity. Just grab your board and go. Anything that adds extra steps gets in the way of that simple, pure experience. And if it ever feels a little sharky, you remember that POD and get peace of mind.

How Shark Hunting Behavior Works

For me and many surfers I’ve talked to, that peace of mind is hard-earned: we want to know in detail why the Sharkbanz technology is effective. To understand, one must first grasp the unique and fascinating way that sharks hunt their prey.

The first major insight into how sharks hunt their prey did not come until 1678, when Stefano Lorenzini detailed his observations on an organ network in the torpedo ray. He noted a pore on the surface of its skin that fed into a canal filled with a jelly-like substance. The biological structure, which is also found in sharks (and other elasmobranchs), became known as the ampullae of Lorenzini.

For 260 years, the purpose of the ampullae of Lorenzini remained a mystery. Then, in 1938, physiologist Alexander Sand confirmed that the organ responds to changes in temperature. In the 1960s, with the benefit of more modern equipment, biologist R. W. Murray found that the ampullae of Lorenzini sent nerve pulses to the brain when exposed to electric fields.

Still, scientists lacked conclusive evidence as to the organ’s purpose. A watershed moment came in October 1971, when biologist Adrianus Kalmijn published a paper documenting how sharks had been able to find hidden prey, despite being unable to hear, smell, or see them.

“[A]ll criteria … now have been satisfied to accredit the animals with an electric sense and to designate the ampullae of Lorenzini as electroreceptors,” Kalmijn wrote.

He included the italicized emphasis in his paper, and for good reason. He’d established conclusive scientific evidence of an entirely new sensory system.

Since then, researchers have expanded their understanding of how sharks use various senses to hunt and attack prey. Initially, sharks are alerted by the scent of blood and the thrash of panicking prey, which they can hear from afar.

As they get closer, sharks engage another set of senses: sight, taste, and the lateral line sense (which detects the displacement of water caused by movement). Within a few feet, the electroreceptors in the ampullae of Lorenzini help sharks pinpoint their prey’s precise location.

Developing a Healthy Respect

As I researched the foundational science for the Sharkbanz technology, I developed a reverence for sharks. In my ignorance — perhaps due in part to the dozens of films depicting sharks as bloodthirsty monsters — I had written them off as something to fear and avoid at all costs. I now began to view them as elegant creatures, in some ways more advanced than humans.

Still, terror flooded through me when Garrison casually mentioned that a friend had spotted a 14-foot great white shark at the same location where we were headed to surf.

“When was this?” I asked, brow furrowed.

Releasing our tie line and pushing off toward that very destination, he wryly answered, “About three months ago.”

“Tell me again about the scientific evidence behind the Sharkbanz technology,” I said.

Fittingly, as we embarked from the Santa Barbara Harbor, we passed a 65-foot diving vessel named Truth, which was exactly what I needed before I got in the water.

Using his thumb to move the POD along his fingers, you might have thought he was about to skip it across the water like a stone. But seeing his eyes narrow as he looked toward the horizon, I think he was reminiscing on his long voyage to get Sharkbanz where it is today.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, finding a reliable, humane means to deter sharks became a pressing issue. Offshore wind farms, bycatch (i.e., the unintended capture of a species while catching other fish) in beach nets and commercial fishing rigs, and shark depredation had all contributed to a global consciousness that the world needed a reliable, ecologically friendly means to deter sharks. As a result, governments and private institutions offered more funding than ever before to research potential solutions.

Scientists took special interest in the last stage of shark attacks, when sharks relied on the electroreceptors in the ampullae of Lorenzini to locate their prey. In a chance occurrence in 2004, organic chemist Eric Stroud and marine biologist Patrick Rice accidentally dropped a magnet into a lab tank containing sharks. They noticed that the sharks seemed to avoid the magnet, and before long, they had launched a series of experiments testing the effects of permanent magnets on sharks.

In 2011, Stroud and Rice, along with Craig P. O’Connell and other researchers, found that lemon sharks avoided the permanent magnets. Based on their research, Stroud and Rice applied for and received a U.S. patent for the use of permanent magnets in deterring sharks.

While Stroud, Rice, and other scientists expanded this body of research, Garrison was on a journey all his own. Garrison fell in love with the ocean at an early age, spending his youth surfing, diving, and fishing near Charleston, South Carolina. In 2006, a bull shark attacked his close friend in nearby Folly Beach, shattering Garrison’s view of the ocean as a carefree sanctuary.

Then, a few years later, while he was working in Santa Barbara for Teva footwear, a neighbor and another local resident died in shark attacks. Shaken by these experiences, he could no longer compartmentalize shark attacks as an abstract fear or a remote risk.

Sharkbanz: When Avoidance Isn’t an Option

Avoiding the ocean altogether was not an option for Garrison; at this point, saltwater flowed through his veins. In 2012, he teamed up with his father, David, a former dive instructor in Monterey Bay during the mid-1970s, and they began researching ways to deter sharks. While most of the research at that time was aimed at shark deterrents for large-scale use, they were focused on helping the individual oceangoer.

Soon, they came across the research demonstrating that sharks, even notoriously aggressive species, exhibit avoidance behavior when they encounter powerful permanent magnets. In 2012, O’Connell and a team of researchers found that permanent magnets were effective in deterring great white sharks. Another study led by O’Connell, in 2014, added bull sharks to the list of shark species repelled by permanent magnets.

Nathan described the discovery as “the crossroads of science and self-preservation.”

The Garrisons immediately understood the industrial value in using permanent magnets to create a wearable shark deterrent. Permanent magnets are unique in that they generate a persistent magnetic field without the need for inducing an electric field or current. In other words, they do not require batteries or a recharging mechanism, which would make a shark deterrent product unduly onerous for customers.

Confident in their findings, they began designing the Sharbanz I. Nathan’s time at Teva prepared him for the challenges of creating wearable products, and he began assembling a team to create a prototype. Within two years, they had secured an exclusive license to use the patented magnetic technology, developed the original Sharkbanz 1 product, and tested the device themselves in shark-riddled waters near the Bahamas.

Dr. Steve Kajiura, professor of biological sciences and leader of the Florida Atlantic University Shark Laboratory, is a subject matter expert in the field of elasmobranch electroreception. He understands the effect of Sharkbanz on sharks better than most.

“Imagine a shark swimming from east to west along the equator,” he said. “It will be passing through the Earth’s magnetic field that runs from the south pole to the north pole. As the shark swims through the magnetic field, it will induce an electric field around itself that is detectable by the electroreceptors in its head. Therefore, the shark is not directly detecting the [Earth’s] magnetic field; rather, it is detecting the electric field that is induced by moving through the magnetic field.

“For the Sharkbanz, there is a strong, local magnetic field that produces a magnetic anomaly. A shark moving past this strong magnet will sense a large electric field which is well beyond the range of anything that it would naturally encounter in the wild. As a result, the shark will be startled by the strong electric field and swim away.”

Making Research More Efficient

When Sharkbanz released its Sharkbanz I, Sharkbanz II, and angler-specific Zeppelin, the company paved the way for easier, more reliable research. Instead of creating their own magnets, scientists could use Sharkbanz products. Not only did this eliminate design variability in the magnets they used, the simple, compact nature of the Sharkbanz products also made research far more convenient.

In 2020 and 2021, the Western Australian government conducted extensive research in shark hot spots near the Montebello Islands to test the effectiveness of the Sharkbanz Zeppelin. Despite the fact that the fish were bleeding, vulnerable, and pursued by one or multiple sharks, researchers found that the Sharkbanz devices reduced the number of fish lost to sharks by about 70% compared to the control. They noted that “sharks abruptly turned away when in close proximity to the [Sharkbanz] device.”

You have to see it to fully comprehend it:

A plethora of additional studies are currently underway, including research by the University of Hawaii, the Harte Research Institute, and Florida Atlantic University. Furthermore, the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has made a concerted effort to fund studies using Sharkbanz under its Restore Program, Sea Grant Program, and Bycatch Reduction Engineering Program. Early reports confirm the effectiveness of Sharkbanz, with published results expected in late 2024 and 2025.

As we neared our surf destination, Garrison explained that both the Zeppelin and the POD have the same patented technology. Though the scientific evidence is compelling, I couldn’t help but point out that the studies mentioned were not based on human trials. I understand the ethical impropriety of using humans as test dummies amid hungry sharks, but ethical considerations didn’t quell my fear of great whites.

As a primary case study, Garrison offers himself, relating how he’s surfed areas all over the world where dangerous sharks have been spotted, including South Africa, Western Australia, Central and Northern California, Florida, and the Channel Islands. By using Sharkbanz and relying on what he calls a common sense approach, he overcame the nagging thoughts in the back of his head in the wake of the shark attacks in communities where he lived.

What Sharkbanz offers is a risk reduction measure, like a helmet, that helps protect you if a shark approaches. Just as you wouldn’t ride into oncoming traffic because you have a helmet on, Sharkbanz products are not meant to encourage you to paddle into a group of hungry sharks.

A Risk Reduction Measure

Scientists and independent researchers like Nathan are forthright that they’ve only grazed the surface when it comes to understanding the biological functions of sharks. Garrison told me the goal has always been to understand how sharks react to this technology and use that information to educate people. In the end, he hopes to foster a sense of coexistence with this incredible animal.

“The more people understand, the less they fear,” Garrison said. “Our job is to educate people so they can better experience the ocean.”

I began to calm down a bit as we anchored the Dos Lunas. Less than a hundred yards from us, chest-to-head-high waves awaited. Though the wind had picked up, the cove we were in kept the conditions nearly immaculate.

Garrison wasted no time getting into his wetsuit, attaching the POD to his leash cuff, and waxing his board. I was moving a tad more slowly, and perhaps sensing that I needed a final nudge, he pulled out his phone, navigated to the Sharkbanz website, and handed me the phone.

“Check out the testimonials from our customers,” he offered. “People send messages like this to us many times a year.”

I scrolled through the thousands of reviews, looking for great white encounters, and found a story from Michael Skogg, who lives in Seaside, Oregon:

“After a cleanup set, I was swimming back to my board when a dorsal fin broke between my board and me. It was a big, dark fin coming at me hard. It got within five or six feet and thrashed really hard — then suddenly, the shark made a violent hard left and bolted out of the area. I wore a Sharkbanz on my right wrist and left ankle. Thank God.”

Greg, Clyde, and Joe encountered a 10-foot tiger shark while surfing in Oahu:

“This morning was the closest encounter I’ve ever had. After being out for an hour or so, another surfer started yelling ‘shark, shark!’, and then I heard, ‘Bruddah he’s heading towards you’. I couldn’t really see the beast until he was about a foot away from the nose of my board and I could see his eyelids start to close. Then about five inches from the tip of the nose, it just took a ninety-degree turn and took off and headed towards my partner who also had the device. Same result, turned away and made his way quickly away from the pack.”

Ivan Trent, a captain in the Navy SEALs and son of legendary surfer Buzzy Trent, had this to say:

“Two months ago while free-diving the Florida Keys, a sizable bull shark approached me from below rather deliberately, to say the least. As I maintained a slow hovering kick he veered off right about 2-3 yards from my left fin, where I placed my Sharkbanz on my ankle, and swiftly darted away. I’m VERY GRATEFUL and want to say, THANK YOU! Life saving product.”

Garrison called to me from the water, and I watched as he paddled into the second wave of a set. He carved turn after turn, and then, wait — did he just get barreled? It was hard to see from my vantage point, because the boat was sidelong to the breakers. As the wave approached the shore, all I saw was the back of the wave rolling forward with the occasional spray out the back from Nathan.

I took another look at the POD attached to my leash cuff and searched the water for looming shadows. I saw none and resolutely leapt into the water with my board.

It was a leap based on science, common sense, and over a decade of technological development. I knew that none of this could completely preclude the possibility of a shark attack, but I can’t deny that I felt better knowing the POD was attached to my leash.

Moments later, I’m next to Nathan, eyes widening as a set approaches.

I quickly settle into a gratifying cycle of catching a wave on the outside, keeping momentum on the reform, and riding the shorebreak to the sand. Then, rather than paddling back out, I run along the beach beneath the cliffs to where the land juts into the sea. From here, I can paddle horizontally back into our two-man lineup, saving my arms for as many rides as my legs can handle.

Letting Go of Fear

Soon, I’ve completely forgotten about the prospect of sharks and the POD attached to my leash. Fully warmed up and comfortable, I catch a peeling right-hander, and euphoria fills me as I see the sunlight glistening through the crest of the wave. I reach the shore and begin sprinting up the beach, energized by the experience and frothing to catch another wave.

I see Nathan has caught a wave on the same set, and I tell him how I feel with a hearty howl. Even from a distance, I can see him smile as he navigates his line.

Later, as we eat dinner on the boat, Nathan and I effusively recount the session. Behind us, the sun sets, while, in front of us, a full moon is on the rise.

Soon, the stoke subsides and exhaustion overcomes me. I collapse in the cabin and vaguely recall being stirred by Nathan in the middle of the night, but he’s unable to get me up.

Later, a sound wakes me. I stumble through the cabin of Dos Lunas, and Nathan is nowhere to be seen. I can hear someone paddling. I peer over the bow into the water and catch a glimpse of Nathan’s silhouette. He’s alone, night surfing under the full moon.

That is peace of mind.

This post was sponsored by Sharkbanz.