The phone rang at about 9:30 a.m. in my home in Denver. The voice on the other end was calm, friendly and clear, like the call was being placed from a cozy living room in the Midwest.

“Are you taking calls from the North Pole?” it asked.

Yes, yes indeed. On the other end of the Iridium satellite phone was Eric Larsen, who, along with teammate Ryan Waters, had reached the geographic North Pole just 12 hours earlier, about 9 p.m. MDT on May 6, 2014.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“I’m kind of sore actually,” he said, in what just might be the understatement of the century. “Yesterday was a real difficult 3.5 miles.”

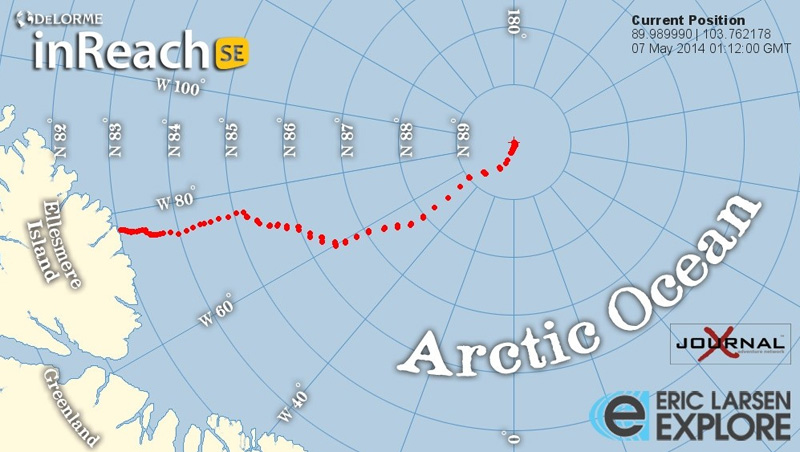

It took the two men 53 days (an American speed record) to slog, swim and ski their way to the North Pole unaided and unsupported, pulling kevlar sleds containing all their supplies that at the beginning of the trip weighed 325 pounds.

In doing so, the “Last North Expedition” was the only team to attempt a “land to Pole” crossing to reach the North Pole this season, and the only successful team since 2010. They are the second American team to complete the crossing, following John Huston and Tyler Fish’s 55-day journey in 2009.

Larsen said that simply experiencing the solitude and beauty of the North Pole was the highlight of the expedition.

“There are moments that you look around and know that nobody else is within hundreds and hundreds of miles,” he said. “It’s so unique, the tongues of blue ice, the snow drifts, it’s amazing that this place exists on this planet and that almost nobody has been here.”

Larsen, who in 2010 became the first person to complete expeditions to the South Pole, North Pole and summit of Mount Everest in a continuous 365-day period, described the 480-mile crossing of shifting sea ice from Canada’s Northern Ellesmere Island as “one of the most difficult expeditions” he has undertaken.

“Physically it’s crazy, but emotionally it’s worse,” he said of the hardest moments of the trip. “There aren’t too many moments that you don’t feel overwhelmed. But being part of a team was incredible. If one of us was down, the other picked him up. Somebody always had your back, which is huge.”

On one occasion, two polar bears came within 15 feet of their sleds. The team also dealt with unusually thin ice, soft slush-like snow, severe windstorms, pressure ridges, and moving ice that pushed their progress backwards.

“You know an expedition is tough when getting stalked by polar bears – who are known to actively seek humans and attack them when hungry – is the least of your worries,” he said.

The expedition mission is to connect people to the planet’s last great frozen places and to raise awareness around the environmental issues that are impacting them.

Followers around the world were able to follow the team’s progress, as Larsen and Waters used real-time tracking and two-way messaging via DeLorme’s inReach SE Communicator with GPS to provide daily audio podcasts, blog posts, social media content, and photos.

“Now, I’m not a scientist, but I’ve spent my life in the snow,” Larsen reported. “I’m seeing climate change first-hand. It’s affecting places like the north pole, where I am now and I’m here because we all need to take notice.”

Larsen partnered with Protect Our Winters and the Climate Reality Project

for the expedition.

Larsen and Waters will be flown back from the pole. I asked him what he most looked forward to when he got home.

“Being with my family,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of expeditions, but now I have (my son) Merritt. I lost two and a half months of his life. He was a baby when I left and now a little boy. I thought I could manage, and I did, but I’ve always said that to see what is most important in life, remove everything, and that’s what an expedition like this does. I realize I don’t need a chair or fancy food, but I do need my family.” —Sean McCoy