By STEPHEN REGENOLD

The year was 1972, and Andy Knapp was hiking alone through tundra in the Brooks Mountain Range of northern Alaska. He was a young man from Roseville, Minn., skinny and 24 years old, trekking solo with an 80-pound pack on his back. A single resupply of food waited days ahead in an Inuit settlement through a 100 miles of trail-less terrain.

Before leaving, Knapp had mailed his parents a set of maps, a line scrawled with his intended route. He’d been sleeping under a tarp, living out of his pack. He hadn’t seen another soul for days.

1972: Knapp hikes solo 502 miles through Alaska’s Brooks Mountain Range

That was before he slipped off a cliff, crashing into a whitewater creek, swimming with a sinking backpack. It was before he fought off the ensuing hypothermia. It was before he tiptoed past a grizzly bear with cubs, a growling beast threatening to charge.

“I got too close trying to snap a photo,” Knapp said.

But Knapp’s Alaska trek — a 502-mile mountain-range-traversing journey — was really just a warm-up to a lifetime of extreme challenges to come, including eight-week-long bicycle rides; mountain climbs past 20,000 feet; kayak trips around Lake Superior, and, since 2003, a battle waged with kidney cancer.

“I’d seen my mortality before; I’d faced huge challenges,” said Knapp, who was 54 at the time of diagnosis. “I decided to draw on my energy and experience in life and apply them to cancer, to try and beat it.”

What ensued was a five-year fight to live, a war with tough-to-treat renal cell carcinoma that started with a string of surgeries and continues to this day with experimental drugs and therapies at the University of Minnesota.

Andy Knapp, December, 2007

Within days of the initial diagnosis, in February 2003, Knapp’s left kidney was removed in an abdominal-severing operation that disabled him for weeks. He took drugs that limited capillary growth in an attempt to starve the tumors. He spent a week immobile in a hospital bed pumped up with 30 pounds of fluids in an immune system-boosting experiment that yielded no positive gain to his condition.

But Knapp, husband to Denise Dohrmann and father of their 15-year-old daughter, Kaitlyn, continued to fight.

He also continued to live life, to play and smile, and to seek more adventures. He stayed active at Midwest Mountaineering, an outdoors shop where he’s worked for 30 years. He continued to bike-commute year-round from his home in south Minneapolis to the store near downtown.

“After a freak-out stage and a why-me stage — things everyone goes through — I accepted that there was nothing I could do but look forward,” he said.

Chemotherapy was not an option with Knapp’s condition. As such, his leg and arm muscles remained relatively unaffected through many cancer treatments, allowing him to bike, ski, hike and, after his abdomen healed, paddle a kayak.

In the past five years, while his condition has waxed and waned, while tumors have grown and shrunk, Knapp’s forward momentum has pushed him to revisit some of the key expeditions of his young adulthood, beginning in the summer of 2004 with a bike trip around Lake Superior. The 1,523-mile pedal north from Minneapolis, looping through Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, into Ontario, then back west to Minnesota and home again, took place almost 40 years to the day after the same trip on a three-speed bike in 1964.

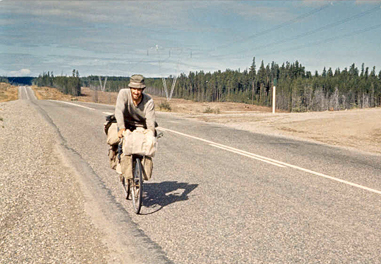

Knapp biking to Alaska in the ’60s.

This past summer, departing on July 7, Knapp set out solo to ride to Alaska. It was the 40th anniversary of a similar trip he started in 1967 with his brother, Steve, and two friends, Howie Graham and Richard Dean Anderson, then an aspiring actor from Roseville who’d grow up to be the star of ABC’s primetime drama “MacGyver.”

As with the 1967 trip, Knapp pedaled northwest through North Dakota to Saskatchewan, on through Canada and finally to the Alaska Highway, where he spun and spun for another 940 miles, riding into the wild.

He had stopped in Edmonton along the way for a required blood test. He kept a blog, updating it every few days for friends. He hauled all his gear in bike panniers, alone and unsupported for a total of 2,655 miles in 24 days. He did it all without fanfare and really for no other reason than, as he puts it, “the joy of motion under your own power.”

“I also wanted to see if I could keep up with the 19-year-old version of myself,” said Knapp, who brought along a photocopy of his 1967 trip journal to compare notes and daily mileage totals. For decades, Knapp has diligently tracked how many miles he’s gone under his own power, starting with a mechanical odometer purchased at Montgomery Wards, then moving on to digital bike gauges and GPS units.

By his count, on the bike alone, he’s cranked through about 123,000 miles over the years. That’s a lot of joy.

Knapp’s condition is currently classified as stabilized, meaning the cancer is not in remission but the tumors have responded to drugs and for now are not growing.

For five years, Knapp has taken one small step at a time with cancer. As he does with a mountain climb, he has mentally broken the fight into segments, each one manageable on its own even if the larger goal looks insurmountable. Each painful therapy, each new experimental drug is a pitch to scale on a steep face. Kick one foot into the snow, rest, breathe, then step up and kick again.

Knapp and his team on the summit of Mt. McKinley.

“Cancer is pain, but it’s more mental than physical,” he said. “Look forward and be positive about your chances; someone has to beat the odds and it may be yourself.”

Knapp has beaten many odds already. He has worked through the medical battles while still living a life full with adventure.

Now, he hopes to see his daughter grow up. In the meantime, he is giving public talks and slide shows. He has a website, www.andytknapp.com, and has plans to write a book. He continues, as he has for his whole life, to evangelize the merits of personal challenge, physical activity and exploration. “The mental strength developed from outdoor skills, adventure and adversity can help you successfully face other challenges in life,” he said.

Knapp once kayaked straight across Lake Superior, from Isle Royale to Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, alone on open water, no land in sight for hours. He paddled into the night, enshrouded in fog but with stars piercing above. The moon arched over the sky. Jupiter rose and was “as bright as Venus,” he said.

For hours he reached and pulled on the deep black plane, a paddle cutting water, moving a man in a small craft through space and time. Knapp could sense the Earth spinning, the vault above tilting. He paddled alone with the stars, a human floating through a void, humbled and happy in a weird way, taking on life, as he always had, as the perpetual, unlimited adventure that it can be.

(Stephen Regenold writes The Gear Junkie column for eleven U.S. newspapers; see www.THEGEARJUNKIE.com for video gear reviews, a daily blog, and an archive of Regenold’s work.)