In June of 1897, the all-Black company of the 25th Mobile Infantry, under the command of a white lieutenant and accompanied by a medic and a journalist, embarked on a journey across America’s heartland — from Fort Missoula, Montana, to St. Louis, Missouri — to “test most thoroughly the bicycle as a means of transportation for troops.”

Their trek would span 41 days and 1,900 miles and pit the men against sandhills, the Rocky Mountains, rain, snow, poison, and more. Decades before Dr. King had his famous dream, these men were sweating together, bleeding together, and biking together as a team.

Their trip proved two truths that we should hold self-evident today: 1) All men are created equal; 2) All men are nowhere near as tough as they were in 1897.

Gears Weren’t Invented Yet

Few people can grasp the physical anguish of traveling nearly 2,000 miles on a bike, save the few elite riders who train a lifetime to ride professional events like the Tour de France. The Tour did not exist in 1897, and neither did gears (the closest thing to blood doping was baking soda).

Not only were the men of the 25th infantry not elite riders, some of them had never so much as ridden a bike (not too surprising considering the bicycle chain had just been invented). Even still, each man pedaled or pushed his bike every inch of the 1,900 miles and did so without “granny gears.”

The Spalding Army Special Bicycle Was Insanely Heavy

Making any 2,000-mile trip by bicycle is impressive. The feat becomes superhuman if that bike weighs 55 pounds, which is exactly what the “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 25th were working with. The bike was 35 pounds of pure steel (the wheels alone were 6 pounds), then add on the Civil War-era tents, poles, change of clothes, toiletries, cooking and eating utensils, spare parts, rifle, and ammunition each man had to carry, and you’ve essentially got a rolling anvil. What’s more, the troop several times had to push these behemoths up the Continental Divide and carry them across rivers.

The Roads Were So Bad They Rode on Train Tracks

As bad as you may think the roads are today, they’re like an endless stretch of undisturbed memory foam compared to the ass-shattering wagon tracks that passed for interstates in 1897. The rocky, rutted mud paths were so bad, in fact, that the men often opted to brave the predictable agony of riding along the railroad tracks instead.

Even more ludicrous, many of the Burlington and Northern Pacific railways in the west were newly constructed, and oftentimes, they lacked any ballast or gravel, meaning between railroad ties were nine-inch-deep holes up to two feet wide. To get some idea of how this might have felt, take an old, heavy steel bike — one you don’t care about too much — and throw it and yourself down a 10-mile flight of stairs twice a day for a month.

Resupply Every 100 Miles

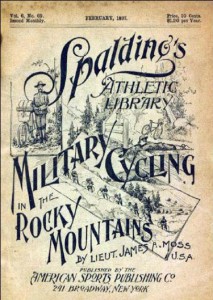

In an effort to keep his men focused and on the move, Lt. James A. Moss arranged supply points at 100-mile intervals along the 1,900-mile route. Considering the men’s capacity to carry at most two days’ worth of rations on their bikes, that made for one hell of a motivated cycling club. When the going was good (tailwind going downhill), the 25th could muster 18 miles per hour.

Unfortunately, the going was almost never good in 1897 and average speed — thanks to washed-out roads, oncoming trains, repair breaks, and the soldiers’ incessant need to eat every day — was a meager 6.5 mph.

So, to reach each checkpoint without starving to death, the infantry routinely pedaled 10 or more hours every day for six weeks.

It Rained 10 Days in the First 2 Weeks, Snowed in June

It’s said that a journey, once begun, is half over. It doesn’t mention that the other half is a miserable soaking march through torrential downpours, a snowstorm in the summer, and a single change of clothes that you can never wash.

Getting rained on riding to work is enough to make most people take the bus. Imagine your frustration if your work were four states away, it had been raining every day for a week, and your bus hadn’t been invented yet. That’s still not as horrifying as having to ride a bike over the Rocky Mountains during a snowfall, which they also did.

Two Days’ Rest in 6 Weeks

That’s right. Though the total trip accumulated 7 days’ worth of “delay” (stops for repairs, lunch, and tire changes), only 2 days out of the 41 traveled did these men not begin their day by climbing into the saddle and ticking off miles from their journey.

They Ate Crackers and Beans, Slept on Cacti

If you’ve never heard of hardtack, it’s because you’ve never sailed across the ocean or served in the American Civil War. These bland, rock-hard biscuits are as difficult to eat as they are to spoil, which is why they were perfect for the 25th’s Sisyphean bike ride across America. This food is so bland that saltine crackers were later invented to improve the flavor.

The only two other modern conveniences (besides crackers that didn’t suck) that would have made life less excruciating are campgrounds and sleeping pads. As it was, the soldiers slept under the stars, wrapped in a wool blanket and on top of the least number of “prickly pear” bushes as possible.

The Water Was Poison

Read that again. As if riding a 55-pound steel bike through snow and rain up a mountain and along railroad tracks for 10 hours a day for 41 days with nothing to eat but crackers wasn’t bat$#!t crazy enough, the 25th drank from a poison water supply.

Specifically, aquifers were often high in alkali, sometimes contained dysentery, and at least once harbored cholera. Despite several members falling ill with these maladies, each man arrived in St. Louis on his bicycle.

Nine Months After the 1,900-Mile Ride, They Went to War

In April 1898, in a response to growing anti-Spanish sentiment and the mysterious sinking of the U.S.S. Maine, the U.S. declared war against Spain. Among the very first troops called to action were those valiant men of the 25th Infantry. Though their testament to the dependability of the bicycle yielded no further exploration into its military use, they’d proven their mettle and their place in history was fixed.

On MLK Day this year, as people gather to sing choruses of “We Shall Overcome,” remember that in 1897, 23 men — some Black, some white — did just that.

Want to learn more? The hour-long PBS documentary below delves into the details of the Bicycle Corps.