Perhaps the most significant differentiator is the three-class e-bike system.

That’s Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3.

If you’ve ever shopped for an e-bike, you’re almost certain to have come across one or more designations. But what exactly do they mean? And where did they come from?

Let’s start with how the U.S. law has defined an e-bike, or more precisely, a “low-speed electric bicycle.”

E-Bike Classes: Legislation and Regulation

Passed by Congress in 2002, H.R. 727 establishes that a low-speed electric bicycle is “a two- or three-wheeled vehicle with fully operable pedals.” It has an electric motor with up to 750 W of power output (1 horsepower) and a maximum motor-propelled speed of 20 mph.

The law separates those bicycles from motorized vehicles, placing them under the purview of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, which regulates bicycles. The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration regulates automobiles, motorcycles (including electrics), and other high-speed vehicles.

However, so-called “e-bikes” within and outside H.R. 727’s parameters were — and continue to be — sold worldwide and end up rolling on roads and bike paths throughout the states. So the U.S. bicycle industry took it upon itself to help bring more order to the emerging e-bike market and help individual states. Each state holds authority over bicycle usage on public roads and bike paths and identifies where e-bikes might safely be ridden.

Industry groups like the Bicycle Product Suppliers Association (BPSA) and PeopleForBikes (PFB) worked together to create the three-class system. (Side note: The BPSA and PFB later merged under the PeopleForBikes name to more effectively coordinate on e-bike policy.)

The first beachhead in the campaign, literally and figuratively, was cycling-rich California. In 2015, the Golden State was the first to pass what PeopleForBikes now calls the “Model Electric Bicycle Law With Classes.”

The 3 E-Bike Classes

Class 1

A bicycle with a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling. It ceases to assist when the bike reaches the speed of 20 mph.

Class 2

A bicycle with a motor that exclusively (typically via a twist throttle or thumb lever) propels the bike. It is incapable of assisting when the bicycle reaches the speed of 20 mph.

Class 3

A bicycle with a motor that provides assistance only when the rider is pedaling. But it ceases to assist when the bike reaches the speed of 28 mph and is equipped with a speedometer.

Power output for all three classes is limited to 750 W/1 horsepower, as outlined in H.R. 727. Class 3 bikes exceed the federal law’s 20mph power-assisted speed limit. But the category is in alignment with the European designation for “speed pedelecs.” This includes e-bikes providing assistance only when the rider is pedaling, with the motor putting out at no more than 45 kph, equaling 28 mph.

‘Reasonable Access’ for E-Bikes

In its role driving e-bike policy, PeopleForBikes maintains that “U.S. laws should permit reasonable access to bicycle infrastructure for the three classes of low-speed electric bicycles, ensure that riders of electric bicycles can enjoy the same duties, protections, and rights as riders of traditional bicycles, and clarify that owners are not subject to vehicle laws that might apply to more powerful devices,” such as licensing.

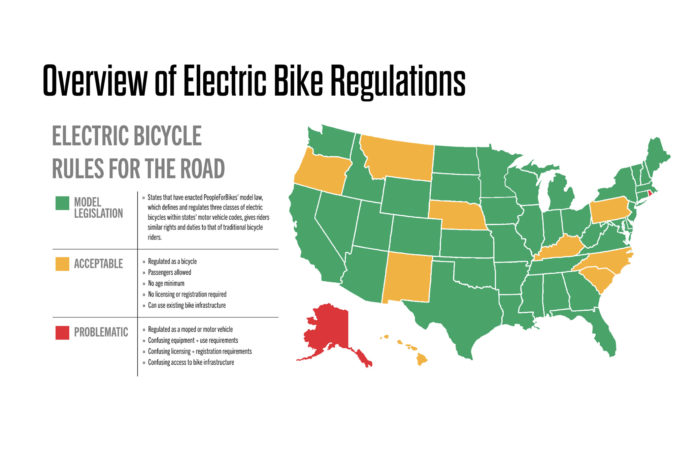

As of this writing, 39 states have passed the three-class system in one form or another. However, significant variances exist from state to state.

Several states restrict or completely bar Class 3 e-bikes on bicycle paths. And New York — where some NYC food delivery workers riding high-speed throttle electric bicycles on roads, bike lanes, and even on sidewalks have stirred anger — created its own Class 3. This class encompasses throttle e-bikes cutting power at 25 mph (for use only in New York City) but does not recognize 28 mph pedal-assist-only e-bikes.

“The more popular e-bikes are — the more people are out riding on various types of bicycle infrastructure — the more these classes come into play,” said Larry Pizzi, an e-bike industry veteran who has been a critical player in the public policy efforts of both the BPSA and PFB. Pizzi currently serves as a chief commercial officer for Alta Cycling Group (home to bicycle and e-bike brands Diamondback, IZIP, and Redline) and sits on the PeopleForBikes’ board of directors.

Out-of-Class E-Bikes

As I said earlier in this story, loads of vehicles that manufacturers call “e-bikes” don’t fit the industry definition the federal law or PFB and its model legislation spell out. These vehicles have higher cutoff speeds for pedal and/or throttle assist. Or the motors exceed the 750W limit — sometimes by a lot. Maybe they don’t even have pedals.

More often than not, these are products made or sold by brands with little or no track record in the bicycle industry. And they’re a problem for the companies looking to promote the safe use of the low-speed electric bicycles they sell.

“It’s detrimental to the rest of the category because they’re well beyond the power and speed criteria that define an electric bicycle,” Pizzi said, adding that building and selling these noncompliant vehicles exposes those brands to incredible financial risk.

Mislabeling of Class 3 E-Bikes Is Another Problem

Case in point: An e-bike with a 750W motor has a thumb throttle powering the bike up to 20 mph, and it also has pedal assist topping out at 28 mph. It’s stickered as a Class 3 e-bike. Is that correct?

Answer: No, it’s outside the class system. Class 3 e-bikes, as outlined by the model legislation, can’t have a throttle even if it tops out at the Class 2 limit of 20 mph. Still, many brands stack the classifications and call these Class 3s. A customer can remove the throttle for Class 3 compliance, but the stock e-bike is out of class.

Regulators have apparently overlooked this mislabeling practice.

“We want governmental organizations to step up and focus on these issues,” Pizzi said. “Our hope is that they’ll reel them in.”