HEAVY METAL MUSIC BLASTED toward the parking lot. Hundreds of racers lined up, bib numbers scrawled in black permanent marker on their foreheads and arms.

It was a Sunday morning at a Tough Mudder event. I’d come to race but also to witness a cultural phenomenon still sweeping the nation.

Founded in 2010 and now drawing hundreds of thousands of participants a year, Tough Mudder events are held around North America and beyond.

My race on July 20th was set in rolling farmland near Hudson, Wis. The venue was a typical Mudder course, with a 10-mile trail lacing together 20 obstacles for a military-style challenge.

A warrior theme prevails, and the company markets that its venues are inspired by British Special Forces training camps. I wore trail running shoes and running shorts, and I have to admit was a little nervous at the starting line.

Fire, electric shocks, heights, and various feats of strength were ahead. “Who here’s ready to go!?” shouted a staffer, leaping up with a microphone in front of the crowd.

I’ve done smaller obstacle races. But Mudder was a whole different level. The atmosphere and energy at the race start were intense.

People were hugging, leaping, shouting, some even praying aloud in groups as we waited to go. A Bible verse was read over the loudspeaker, something from Psalms that mentioned “climbing walls.”

The religious shout-outs stood in strange incongruence to the music blasting, which hurt my ears and screeched lyrics about the “death of angels.”

I was becoming unnerved and the race had still to start. But then with more music, and “Hooahs!” shouted out, and fist-pumping, the announcer yelped GO! GO! GO!

The race pack jumped to motion, the muscled shirtless bodies of young men taking the lead. They sprinted down the chute on a course unranked and un-timed.

Completing the Mudder is what matters, a staffer had said earlier to the group. Still, he continued, “22 percent of you won’t make it to the end.”

I’m an experienced runner, and the 10 miles ahead were not a concern. But flames, ropes, pits of mud, and greasy wooden walls? My experience does not skew toward military or masochistic themes.

Happily, the mud and the obstacles turned out to be a ton of fun. We climbed a wall right away. I was coated in brown sludge less than a mile from the start.

Next came the “Pole Dancer” obstacle, which made racers traverse a pit on a set of parallel bars. “Keep your elbows locked,” a fellow racer advised as I grabbed hold.

We worked as a team on the “Warrior Carry,” where each person piggy-backs a fellow racer. Then it was into a large tub of ice water a half-mile further. I leapt into the cited 34-degree water and swam as every muscle in my body contracted from the cold.

Invigorated, I sprinted for a while, passing racers who were walking, jogging, and even stumbling less than halfway through the course. It was inspiring to see people push their limits.

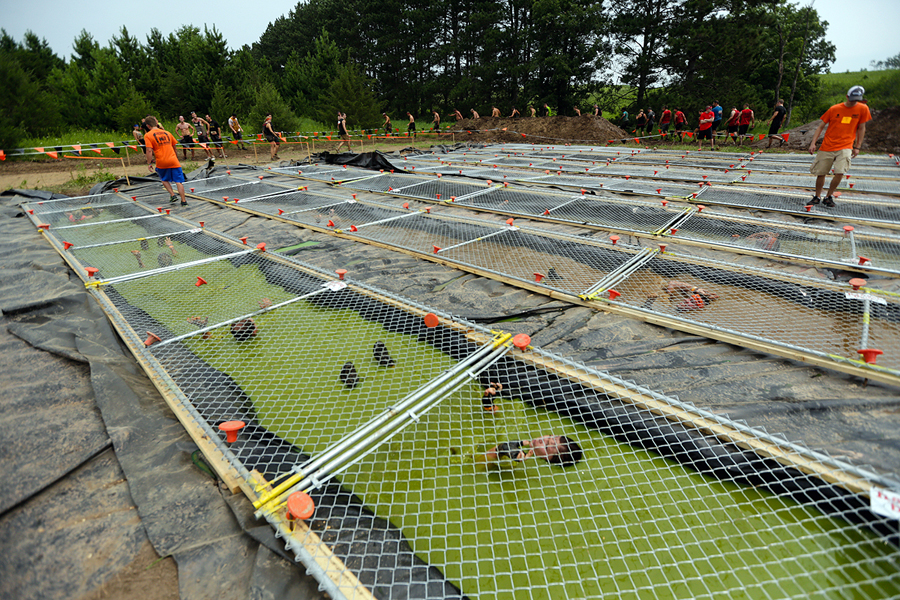

Each obstacle ahead — nets, trenches, pits, monkey bars, and more wooden walls — offered a challenge and, once accomplished, a sense of completion within the context of the larger race.

Just before the end was the “Everest” obstacle, a famous half-pipe you attempt to run up. I sprinted and made it on the first try.

Finally, teasing in front of the finish line, were a nest of dangling wires known as “Electroshock Therapy.”

I stopped to survey the challenge, which is purported to deliver 10,000-volt shocks. A woman ahead screamed as a wire touched her back.

In a burst I ran, pushing the wisps out of the way. But one caught me and buzzed, a startling wave of electricity traveling diagonally across my trunk, exiting in a ticklish, painful spasm on the back of my leg.

Across the finish line I laughed from the sheer oddity of what I had just done. Muddy and beat after the 10 miles I grabbed a finisher’s headband and turned around.

From the line I could see obstacles with fire, mud, electricity, water, ladders, and walls. Racers ran solo and in groups toward the end, alternately wincing or smiling, side by side, the drama of humans pushing limits in various states of pain and joy.

—Stephen Regenold is editor and founder of GearJunkie. He wrote about his experience in the Gaelforce North Adventure Race in Ireland last month.