For decades, the precipitous trail through Hey Joe Canyon offered Moab off roaders an iconic experience of the area’s world-famous rock formations. But now it’s one of many classic trails closed to motorized recreation by federal officials. While some environmental groups laud the closures, opponents say they make access more difficult for everyone.

“For someone to access that now is severely limited,” said Joe Risi, Senior PR Manager for onX Offroad. “It limits those that are healthy and able, not just the young, old and disabled. Where I park my car, where I unload my bike, how much water I need to bring: It’s all been rocked by this.”

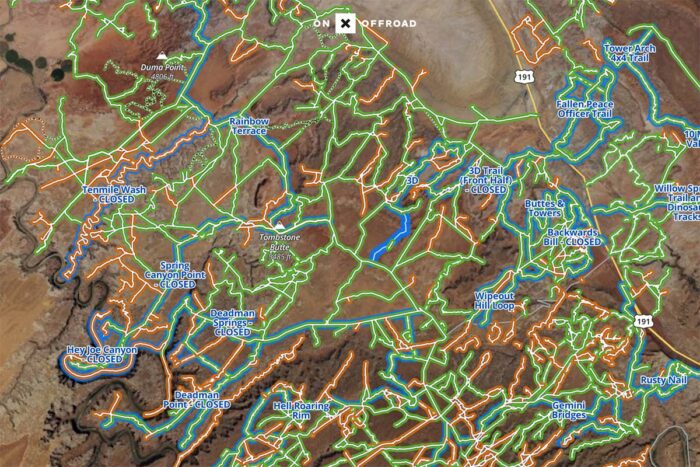

The mapping engineers at onX know better than most just how quickly land access in Moab is changing. They’ve spent the last several weeks updating the onX Offroad app as quickly as possible after the U.S. Bureau of Land Management announced a plan on Sept. 28 to close about 317 miles of Moab trails to motorized vehicles.

That decision led to widespread outrage from the off-roading community. In terms of density, it’s the largest single closure on the onX Offroad app since it was released in 2019. Roads in Hey Joe Canyon, 10-Mile Wash, Dead Cow, and Hell Roaring Canyon are now closed to anything with a motor, including e-bikes. The changes affect not only motorists, but also hikers and mountain bikers who will have a harder time reaching trailheads.

“Moab has become an iconic off-roading mecca. These trails are loved by this community, and that’s where it hits home,” said Risi. “But it also creates access problems for everyone. Many people don’t understand that.”

Environmentalists cheered the closures as a win for Utah wilderness. But legal challenges filed this week will attempt to stop federal authorities from moving forward with the plan. One thing is certain: The battle over the future of Utah land access is just getting started.

A Win for Wilderness Advocates

When the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) announced the trail closures, environmental advocates immediately welcomed the news. The closures will protect cultural sites, river habitats, and the “experience” of non-motorized recreationists, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) said in a news release on Sept. 28.

“Visitors will finally be able to experience stunning Labyrinth Canyon without the noise, dust, and damage that accompanies motorized recreation,” said Laura Peterson, SUWA’s staff attorney. “For too long, the BLM has prioritized off-road vehicle use at the expense of Utah’s incredible natural and cultural resources. The Labyrinth Canyon plan represents an important step forward to guide the management of Utah’s public lands and reduce the impacts of off-road vehicle routes in this area.”

SUWA pointed at powerful off-road vehicles as a rising source of problems in the area, with “noise and dust disproportionately impacting the majority of public land users,” the organization said. But the trail closures don’t just affect the ATVs and UHVs (also known as side-by-sides). Even electric Jeeps, dirt bikes, and e-bikes are prohibited under the new access rules for about a third of the area, which includes 300,000 acres of public land in Grand County, Utah.

Both SUWA and BLM highlighted the many trails still available to off roaders. The large chunk of territory managed by BLM’s plan will still offer 800 miles of dirt trails to off-roaders.

But the popular Green River and many of its side canyons are now off-limits to motorized recreation. For off-roading groups — and the State of Utah — that’s not good enough. If federal officials and environmental advocates want to achieve “balance” between motorized and non-motorized recreation, this isn’t it, said Patrick McKay of the Colorado Offroad Trail Defenders.

“This brings balance to the outdoors the way Anakin Skywalker brought balance to the force by killing all the good guys,” McKay said. “That’s not balance.”

Legal Challenges to BLM Plan

The debate over land access in Moab often centers on the side-by-sides, or UHVs. These loud, burly off-road vehicles are popular among tourists who use them to cruise through remote parts of the Moab area, often waving colored lightsticks and blasting music.

But the impact of BLM’s new rules impact far more than those controversial vehicles. While BLM and SUWA have downplayed the impact to other recreationists, some locals feel concerned.

“This is huge for the area. There’s been nothing of this magnitude before,” said Jason Taylor, who has served as Utah Operations Manager for Moab Adventure Center for 20 years. “We definitely watch this stuff very closely.”

Several of the closed routes are used during the Easter Jeep Safari, one of Moab’s oldest events and a big tourist attraction. Managers for Red Rock 4-Wheelers, which manages the event, did not respond to requests for comment.

Other groups, however, have already taken action. On Monday, the Blue Ribbon Coalition and Colorado Offroad Trail Defenders appealed the federal plan. The State of Utah also announced a legal challenge, claiming that the BLM failed to balance conservation with recreation. Both appeals have requested a stay on the closures through the Interior Board of Land Appeals, which has 45 days to make a decision.

If a stay is granted, then federal officials must postpone implementing the plan, said Nicole Gaddis-Wyatt, a BLM District Manager. Implementation involves federal officials putting up signage informing drivers of the closures. In the meantime, the trails are likely closed per the new rules.

For those caught using the trails illegally, penalties could include a $1,000 fine and imprisonment up to 12 months.

An Uncertain Future for Moab Trails

For some, off-roading might conjure up images of irresponsible teenagers whooping their way through the desert. But many Jeep trails near Moab — including several iconic trails closed under the BLM plan — offer a chance for elderly and disabled people to explore places they could never reach otherwise.

More importantly, nearly every “user group” enjoying the Moab scenery is relying on a motorized vehicle of some kind, said Ben Burr, executive director of the Blue Ribbon Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for outdoor recreation. Like many sources interviewed for this story, Burr criticized the idea that the BLM’s plan actually achieves “balance” between various groups.

Dispersed campers? They’re impacted by this, Burr said. The same goes for hikers, mountain bikers and Green River paddlers using vehicles to reach the start of their Moab adventure. And this isn’t the first time federal officials have closed trails near Moab. Many others were closed after a 2008 management plan from BLM.

“One day they will close something that you like, that’s your favorite place,” Burr said. “So it’s time to wake up and start participating in this process.”

There’s little doubt the debate will continue over how to achieve balance in land access. But Moab locals like Taylor have a good idea of what that means for the future.

“We live in an area where people come to recreate. They come out here to get away from their suburban settings, and they have as much right to be out here as us locals do,” Taylor said. “We need to strike a balance where that’s possible, but also protects the environment for future generations … No one’s gonna be happy and get everything they want.”