Contributing editor Jeff Kish is hiking the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail this summer. This is his fifth report from the trail. See Kish’s full collection of trip reports and gear reviews at GearJunkie.com/PNT.

My dad taught me a lot when I was a kid. But when I look back two of his favorite mantras really stand out:

“Do the right thing.” I heard that all the time, often when I needed the reminder that the right thing isn’t always the fun thing, or the easy thing, or the popular thing. It was about demonstrating your integrity and acting on your beliefs about what was proper, fair and just.

The second mantra was: “Always leave things better than you found them.”

Whether that referred to the condition I left the workbench after tinkering around with his tools, or picking up other people’s discarded tangles of fishing line down by the lake, it was not just about accountability for my own actions, but duty for the greater good.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the implementation of the Wilderness Act, which defined what Wilderness is and set aside an initial 9.1 million acres of public land for that purpose.

When Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law, he famously said: “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it.”

The Wilderness Act is the embodiment of “Do the right thing” and “Leave things better than you found them.” Just as the generations before ours instilled us with values like my father’s, they led by example, looking beyond the short term gains they could extract from our lands and recognizing these unspoiled tracts for their intrinsic worth.

This past week, on the eve of the Wilderness Act’s 50th birthday, my girlfriend Hannah and I enjoyed the fruits of these efforts as we completed an eight-day traverse of Washington’s Pasayten Wilderness on the Pacific Northwest Trail.

The landscape was awe-inspiring — old-growth forests filled the lowlands where 1,000-year-old cedars rose from the soggy mosses of the forest floor. Butterflies fluttered through the breeze from wildflower to wildflower around tranquil ponds in pristine alpine meadows.

Pikas scampered through the rubble of talus at the foot of jagged untamed peaks, and mountain goat tracks and ancient lichens dotted the crags that jutted up into the heavens.

After two days of hiking through steady rains and temperatures that dipped into the 30s, we came to a set of old cabins that sat in a clearing above the remains of an old tungsten mine.

They had been built in the 1930s and showed many signs of their age, but their roofs held out the rain and each was equipped with a small wood-burning stove, offering a welcome respite from the soggy conditions.

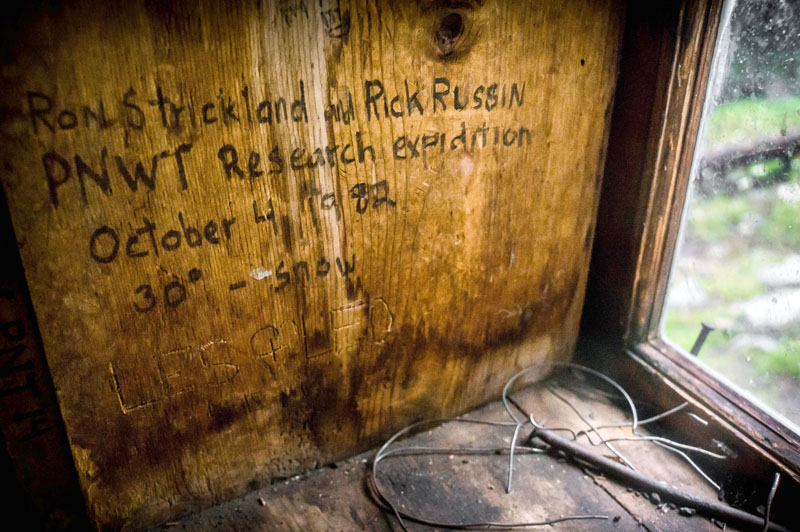

The walls were etched with decades of history. Among the names and dates where the first men to thru-hike the Pacific Northwest Trail in 1977, and an entry from Ron Strickland himself, made during an exploratory trip in 1982.

We unpacked our things and hung them around the cabin to dry, then we occupied ourselves as we had for the last several days, pouring out our hearts in a seamless stream of conversation and sharing stories from our pasts while listening to the rain pound on the weathered roof.

There was an old mining cart in one corner next to the stove and a wood crate in the other. The collection of splinters and bark piled in their bottoms showed that they were used to hold logs to feed the fire, but they were empty now. We looked inside the stove but only found carelessly discarded plastic and foil wrappers stuffed inside.

That’s when I told Hannah about my father’s code.

With most of the day still ahead of us, we decided to see what we could do to leave the cabin a little better than we found it. We fished the trash out of the stove, swept the floors, and with the few dry twigs that we could salvage from the bottom of the cart, we started a small fire.

We collected wet branches from downed trees outside and stacked them across the warm top of the stove until they dried, slowly refilling the crates with our bounty for the next travelers to use.

From the creation of the Wilderness Act, which set aside the land for future generations, to groups like the Back Country Horsemen, a volunteer organization that maintains trails across the country where motorized vehicles cannot go, and even to our own small efforts on that rainy day, wilderness stands for more than just protected land. It’s a symbol that shows that people are still capable of doing the right thing.

The rain cleared overnight, and we hiked back out across the wilderness the next morning. Over the coming few days we climbed Cathedral Peak and gazed out over the Pasayten’s massive wild expanse.

We traversed calm meadows, dense forests, and lofty passes. We climbed Devil’s Dome and ate lunch surrounded by a panorama of rugged peaks, and then we finally dropped down out of the Pasayten into Ross Lake for the end of the section that we’d share together.

The 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act is not only a time for celebration, but also a time to reflect on how our generation can continue carrying on this legacy. I urge you to visit the following links and consider how you can get involved!

—Contributing editor Jeff Kish is hiking the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail this summer. He will be making regular trip reports and gear reviews from the trail. Follow the whole journey at GearJunkie.com/PNT.