Fifty hours of walking, slogging, and camping in a swamp may not sound like your ideal adventure weekend. But for a race director, an ecologist, and an endurance athlete it was the expedition of a lifetime.

Last month, three men traversed one of the largest swaths of terra (in)firma in the Lower 48.

John Storkamp of Rocksteady Running, botanist/ecologist Jason Husveth, and ultrarunner Rob Henderson drove to the northern reaches of Minnesota. The goal was to access by (soggy) feet a natural area that very few, if any, humans have ever seen.

Backing up, “swamp” probably isn’t a fair assessment. The spongy, otherworldly biome is actually a thriving peatland preserve and among the continent’s largest biomass sinks.

In fact, it’s bigger than Rhode Island and stretches to the horizons as an expanse of partially-decayed vegetation, organic matter, and sphagnum moss.

It’s an alien kind of place, which was one draw. But it’s also a pure physical challenge with total immersion in nature. (Note: The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources approved a special research permit to allow for this traverse of a protected state scientific and natural area.)

Here, Storkamp chronicles the journey: a 50-hour, 43-mile trip he described as “a long-time dream.”

‘Red Lake Peatland Crossing’ (by John Storkamp)

My friend and colleague Jason Husveth hatched the project. He is, like me, an ultra-marathon runner and outdoorsman. And he’s an ecologist working on wetland restoration. So he’s a native-plant identification nerd and happens to be one of the state’s leading experts on native sedges, ferns, and orchids.

Jason’s company is Critical Connections Ecological Services. I moonlight as a field technician with his firm, and we have spent countless hours and miles in wetlands and bogs in Northern Minnesota over the years—both for work and play.

This latest trip, however, was a pet project. Our goal was to access areas that very few humans ever have.

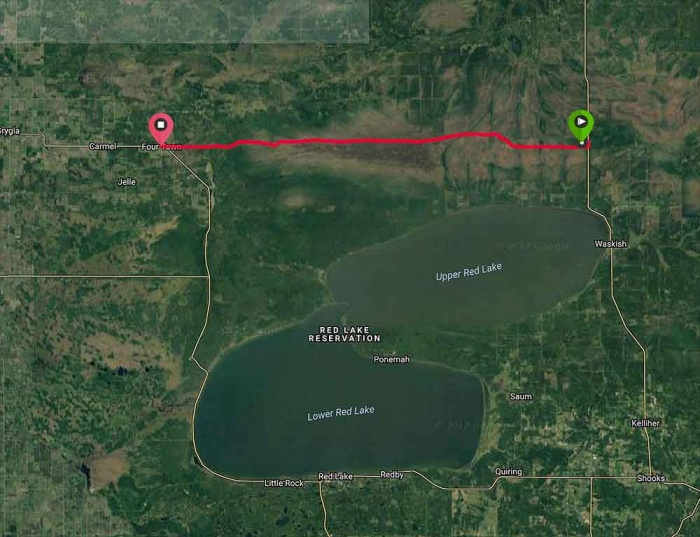

Our mission was a complete east-to-west traverse of the Red Lake Peatland via the Western Water Track. Scientists are normally the only ones to visit the area—from helicopter.

Also along for the trip was Rob Henderson, an experienced backpacker and ultrarunner. The trip spanned three days, two nights, and 43 miles, all covered in 50 hours with a total of 16 hours of rest.

Light Gear, Slow Going

To stay as light as possible we went with only bivy sacks and did not use sleeping bags. Needless to say, it was slow going. There were times we were able to move as quickly as three mph, but other times we could only cover about one mile every two hours.

A side note: We tried this same crossing last winter, and the day we set out it was -33° F. But weirdly, we still found lots of thin ice and liquid water in the bog.

We abandoned after the first day because of breaking through the ice and getting into water numerous times. Those conditions made forward progress so slow and arduous that there was no choice but to abandon the attempt.

For our summer bog trip, we did not use any special gear on our feet. We wore trail-running shoes with wool socks because running shoes drain well.

On good “floating-mats” we sank anywhere from four to eight inches regularly. The entire mat of vegetation compressed and moved – imagine walking on a waterbed!

In the not-so-solid areas, there was either standing water on top of the mat, or you broke through, and your foot and leg plunged into the water below. And in the more acidic areas with sphagnum moss, we often sank down a foot, maybe more.

Some of the slowest stuff we encountered were bog shrubs mixed in with sphagnum. And of course, the forested edges on the way out involved deep bushwhacking and were brutally slow.

In the end, running shoes and wool socks—and having feet that are used to doing this kind of stuff and being wet hours on end—was the key. With enough time to dry out a little at night, we avoided trench foot and other maladies.

But the grueling trek and mucky conditions were a reminder that this is not a place for humans. It’s thankfully protected, and hospitable solely to its thriving wetland flora and biome.

It was an honor to see, smell, and feel this place. But it belongs to the wild, and the world is better with these empty places.

–John Storkamp is the founder of Rocksteady Running. We interviewed him about the Arrowhead 135 winter race in 2016.