Two Black women are launching a digital platform that will locate Black-friendly businesses across the country, aiding our fellow Black citizens in remaining as safe as possible as they travel.

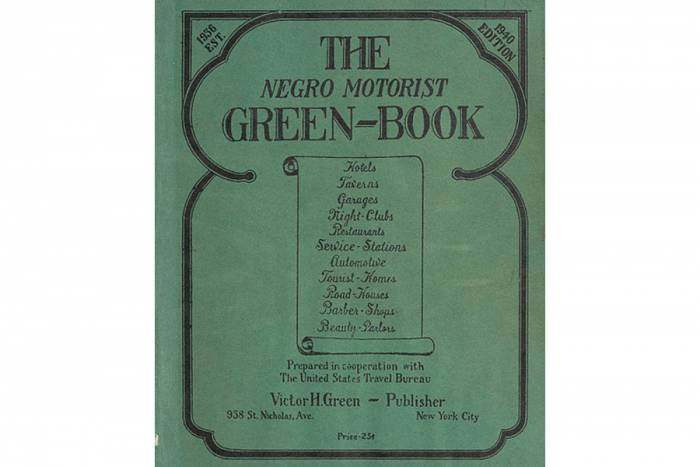

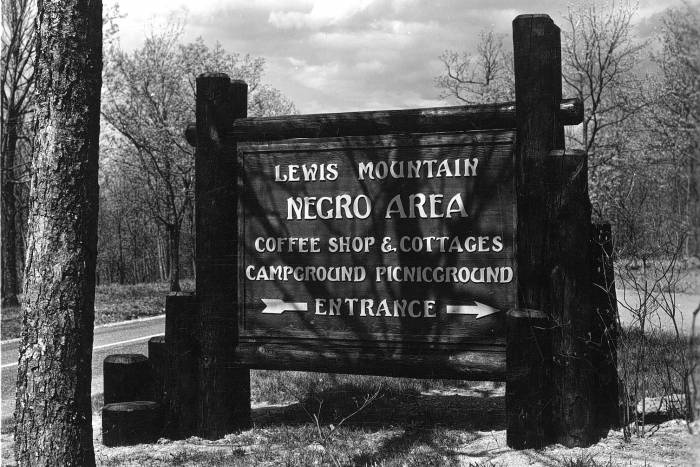

The Original Green Book is an astonishing and important tool that kept Black Americans safe in the Jim Crow era. Back then, racism was less than subtle. Black people were not allowed to use public restrooms, eat at many restaurants, stay in many hotels, or even get care at beauty shops or go to nightclubs. But some businesses broke that barrier and welcomed Black travelers into their spaces.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book,” first published in 1936, closed the gap between Black travelers and safer spaces. A slim book, it was created by a postal worker named Victor H. Green. He used his postal contacts to determine what businesses and families would take in Black travelers and shelter them safely. It was last published in 1967. And by that point, it covered all 50 U.S. states and a few other countries.

It’s been 53 years since the last Green Book hit the stands, but unfortunately, racism still abounds.

Two Black women — Crystal Egli and Parker McMullen Bushman — are working to fund the Digital Green Book, a website that will bring the action of the original “Green Book” into the 21st century.

We sat down with them to better understand the impetus behind the new Digital Green Book. Their thoughts, experiences, and goals for this site challenge the mindset that today is much different than the Jim Crow era.

‘Digital Green Book’: Interview With the Founders

GearJunkie: What was the impetus for the Digital Green Book?

Egli: I grew up in rural Vermont as one of the very few minorities. However, my mom was everyone’s doctor, so everyone knew who I was and I never had too many issues.

There were towns I knew to avoid completely. I got refused service at knifepoint once in a fast-food restaurant. People called me racist things here and there. But I was unknowingly in a huge bubble of privilege that was extended to me through my white adoptive parents.

I grew up hiking, water skiing, and fishing, I took sailing lessons at summer camp, and I just thought I didn’t see other people like me doing these things because there weren’t any around. It wasn’t until I moved to Boston for college, then California, and eventually Colorado that I began to realize my privilege bubble didn’t extend very far at all. In fact, it pretty much popped the second I left rural Vermont.

I didn’t feel safe jogging alone; I was being followed around stores for the first time. People were glaring at me for no reason, and life generally began to get just a little shakier.

I started looking over my shoulder for the first time. I’d test store employees by walking around in random patterns to see if they really were following me. I quickly learned to keep my hands out of my pockets, and I’d make eye contact with employees. I learned to always ask if I can keep my bag with me when I entered stores, things like that. And I learned to deal.

Things shifted for me when I took up hunting a few years ago. Now I have all this going on, and I’m supposed to be walking around with a gun? When I confided in my white friends and co-workers about this fear, no one seemed to believe me. I got answers like, “But it’s your right to be able to carry a gun,” and, “You’ll be wearing orange, so won’t it be obvious you’re a hunter?”

Black people are getting shot for sleeping in their beds, and getting cops called on them for encouraging others to follow the rules while birdwatching. Do you think a little blaze-orange is going to stop someone from calling the cops on an armed Black lady? I’m not taking that risk.

I realized I could really use a Yelp or Trip Advisor for safe spaces, a place where I’d be believed and heard, a place where I could tell others they’d be safe here or there. It turns out, that doesn’t exist, but it did once. The original Green Book was an absolutely essential guide for Black travelers. Having it with you could mean the difference between life and death — literally.

Bushman: As a Black woman, I never know when someone’s bias, unconscious or conscious, is going to affect the way that they serve me. I’ve been in so many situations where I’ve been made to feel uncomfortable or unsafe in a space.

It happens every day to people of color. It happens to people in other marginalized groups as well. Usually, when people have those experiences, they move on quietly. They might talk to their friends and family about how they felt, but it usually doesn’t go beyond that.

That’s what makes this Digital Green book project so powerful: a collective voice so people can find safe spaces where they can feel comfortable and welcomed.

Tell us about the modern need for a Digital Green Book. Why now?

Egli: Society at large has been tricked into thinking racism is a thing of the past.

For example, when you see a documentary about the Civil Rights movement, they interview leaders who fought for justice and equality, the ones who made it through and are our elders to this day.

But they only show footage of the hate crimes and the white supremacists committing acts of violence in black and white, and we forget that they are still alive too. They are still out there. They’re just a little bit more careful about it.

The Green Book was a very important tool in the northern part of the country because even though there were fewer “colored” and “white” signs clearly indicating segregated spaces, you could still face the same dangers without realizing it. That is what the Green Book was mostly for: teaching Black travelers how to navigate racism where they couldn’t see it clearly posted.

It turns out we still need that. This is especially true because racism is so ingrained into every one of us that people as individuals don’t even acknowledge to themselves that they are practicing racial bias. The Digital Green Book website will hold businesses and public spaces accountable not for their intent but for their impact.

Bushman: When Crystal and I first began discussing this project, we realized the possibilities are endless. We could create a space where people could go and find businesses that were working to be intentionally welcoming to all. And we could highlight businesses of color so that those that wanted to support them could have an easy place to find them.

We also realize that this could be a powerful tool for businesses. Websites that allow businesses to receive feedback from their customers help them to improve their customer service. Oftentimes, businesses don’t even realize that they may have a space that is not welcoming to all of their customers. And even if someone tells them, they don’t necessarily know what changes they need to make.

We feel that this website could also provide resources for businesses looking to be more inclusive. We also realize that having data would be a powerful tool for encouraging businesses to make changes. This way businesses can see in what ways they are being really welcoming and in what place they are missing the mark.

How do you see it working? Do you foresee it becoming an app?

Egli: Our intent is to stay as true to the original Green Book methodology as possible while utilizing new technology to be as inclusive as we can in order to serve a wide range of marginalized identities.

The original Green Book was published with user-generated content. People would mail business listings to Victor H. Green, and he would add them into the book. It is very important to note that he believed the submissions. I’ve personally been wrestling with the idea of, how can we know that these submissions are accurate? Then I remembered how I felt when no one believed me, and I realized that at some point we need to start believing experience over data.

That being said, there was also a mechanism in play for the original Green Book where you could let them know when you believed a mistake might have been made. They would then look into the claim. We do plan on having a system of checks and balances. But first and foremost I want to make sure we value the personal experiences of marginalized people. I want to be part of the new system that says, “We hear you, we believe you, and we will work to hold them accountable.”

Bushman: This website will thrive from crowd-sourced information. We plan to seed the site at first with businesses that have a reputation for inclusion and businesses owned and operated by people from marginalized identities. But the ultimate goal is to have members of the community and businesses submit listings themselves.

We want to have people who have visited those businesses give feedback and rank the business on certain attributes. We would also like to have physical attributes of the space listed. Like is it accessible to people utilizing wheelchairs? Are there gender-neutral bathrooms available?

We have also talked about eventually providing businesses that rank high in inclusion some type of visibility through a sticker that they can put on their entry door. That way customers can understand on sight that these businesses are working to be intentionally inclusive to all. We hope it would also be an encouragement for other businesses to work on it.

Eventually, we would like it to be an app. It will be important for ease of use.

What will this mean for the Black community? What will it mean for you both personally?

Egli: I love being outdoors, I love everything about it. I hate to limit the places I can go because I don’t feel comfortable just hitting the road and stopping anywhere I feel like it.

But at some point, I’d like to have just one vacation where I’m not constantly getting stared at, go on one trip I can take where my white husband and I can go to a restaurant and I’m not constantly scanning for who is looking at us. If I could plan a whole trip around safe spaces, well, maybe I’d start finding vacations relaxing!

On a larger scale, I just want people to know that their experiences matter. I want to give them a sense of control over it and let them know that the community at large has their backs. I want them to know that I do think it’s a big deal they got stares in a gas station, I want them to know that I do think it’s a big deal that they got followed around that gift shop.

I want them to know that we will take them seriously, no matter how big or small their discomfort was, and that it doesn’t matter if it didn’t result in an altercation or even if no words were spoken.

It’s still not right, and we are here to do something about it.

Bushman: For the Black community, I believe this website will be significant. When we walk into an establishment, we shouldn’t have to wonder if our interactions there will end in the police being called.

In January of this year, a Black man had the cops called on him at a bank while trying to deposit a settlement check. The bank called the police on accusations that the check was fraudulent. The ironic thing about it is that the check was a settlement check from a workplace racial discrimination lawsuit.

Again and again, we see Black people being profiled, followed, and even having the police called on them for just trying to exist in public.

That is why for me personally this website would be a huge game-changer. When I interact in my daily life, whether it’s traveling or at home, I want to use businesses that I know respect me. I want to use my money to support businesses that have inclusion as a core business value.

How do you envision the Digital Green Book evolving for Black folks in the foreseeable future? I know you plan to expand for other marginalized folks as well. Do you want to speak to that?

Egli: We have so many plans! Right now, we are focused on Black voices and the Black experience. We wanted to start there because that is what the original Green Book was focused on, and this is the lived experience Parker and I have to start with. However, it’s very hard for us to not jump right into making this site with all the features needed to help other marginalized communities from the start.

The LGBTQ+ community is so important to include. It can be incredibly dangerous for them as well, sometimes even more so. We are also very passionate about providing accessibility information. I’ve seen way too many restaurants with bathrooms only accessible by stairs. There’s even a police department in L.A. that is only accessible by stairs.

When places do technically meet ADA requirements, it can still be extremely difficult to navigate for a person who uses adaptive equipment. And let’s not forget the weird vibes employees can give off when attempting to assist.

The more money we can raise upfront, the more features we can afford to have designed and the more people we can serve. Additionally, we want to let everyone know that this website will be providing resources for businesses and organizations to help their spaces be more inclusive and welcoming. We’re not just gonna burn ’em publicly and let them go out of business. That’s not what this is about.

We want to hold businesses and spaces accountable, yes, but we also want to let them know we are here to help them as well. We will provide resources such as recommendations for professional trainers, book lists, film and video recommendations, and so on. We’re actually very excited about this part because this is Parker’s area of expertise. She rocks at it.

Bushman: I am excited by how we hope to grow the scope of this project. We would like this to eventually be a one-stop shop for inclusion.

We understand that across the spectrum of diversity and marginalized groups, people of color at the intersection of identities often bear the brunt of negative impacts. So if you are Black and have a disability, your negative impacts are compounded. If you are Black and a transwoman, you are at a higher risk of homelessness, violence, and death.

We want this website to address that intersectionality so that all members of our communities can find safe spaces.