By Krista Langlois

This week, Congress is looking at a bill that even a few years ago seemed wildly, laughably improbable: an authorization to spend $250 million to implement a reworked version of the historic 2010 Klamath River agreements.

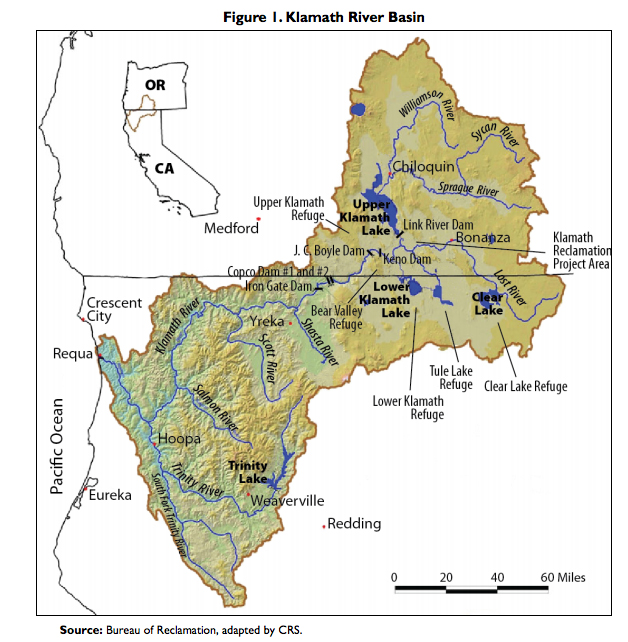

The Senate bill is a mere 42 words long, but it seeks nothing less than to seal the fate of one of the most embattled waterways in the American West. And oh yeah – it also paves the way for the largest dam removal in U.S. history, knocking out four dams, opening up 420 miles of habitat and restoring salmon runs by an estimated 80 percent. No big deal.

Though the bill itself is brief, its passage would put into motion the actions outlined in the 93-page Klamath Basin Comprehensive Agreement, a landmark document signed this spring by farmers, tribes and politicians. Under the agreement, the Klamath Tribes, who now hold senior water rights, will save water for downstream irrigators and wildlife refuges in exchange for funds to help with economic development and restoring salmon habitat. Plus, utility company PacifiCorp will demolish its four salmon-blocking dams by 2020, paid for through a small utility surcharge and replaced by a federal utility that may include large-scale solar. With a few exceptions, nearly all stakeholders on the ground support the measures. All that’s left is for Congress to sign off.

So will it? Given that said bill is sponsored by four West Coast Democrats, the chances are slim. Nonetheless, there is a chance, and invested parties – including PacifiCorp – are determined to push legislation through one way or another. So in case you’re still scratching your head over where the heck the Klamath River is and why it’s so embattled, here’s a primer:

1903 – The first of five dams that now spool out up to 169 megawatts of electricity for PacifiCorp is built on the Klamath.

1956 – PacifiCorp enters into a fixed-price agreement with Klamath ranchers and farmers that will keep their power rates abnormally low for 50 years. In exchange, the farmers promise to return irrigation water to the river to be run through turbines.

1973 – The Endangered Species Act is passed, imposing minimum stream flows to keep threatened fish alive and setting the stage for future “fish versus farmers” battles on the Klamath and elsewhere.

2001 – Severe drought kicks the Klamath basin in the teeth. Federal officials shut off some farmers’ irrigation water to save fish protected by the ESA; farmers lose between $27 and $47 million. A shooting spree and death threats ensue.

2002 – The Bush administration ensures that farmers get their water – and cause one of the largest die-offs of adult salmon in Western history, infuriating Native tribes.

2004 – As the fixed-price contracts near their expiration date, PacifiCorp announces a rate hike of a thousand percent to bring farmers’ and ranchers’ power bills up to date. “Nothing brings people together like a common enemy,” Yurok Indian Troy Fletcher told High Country News. Indeed, the hike prompted farmers and tribes to begin talking.

2007 – The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ruled that fish ladders would be necessary for the dams to stay in operation. Implementing fish passage and maintaining the aging dams proved costlier than removing them outright.

2009 – Hoping that an ongoing legal fight will ultimately grant them senior water rights, some ranchers drop out of negotiations.

2010 – The remaining stakeholders sign two agreements to settle disputes, restore habitat, ensure stable irrigation flow and remove dams, but the agreements are missing several components and some tribes, environmental groups and ranchers aren’t onboard.

2011 – Congress fails to take action on a bill that would have authorized the 2010 agreements, and calls for a lower-cost, more-inclusive solution.

February 2013 – A 400-page Department of the Interior report finds that the financial benefit of removing the dams outweighs the cost of keeping them by a ratio of nearly 48 to 1.

March 2013 – The state of Oregon officially recognizes the Klamath Tribes as the most senior water-rights holders in the Upper Klamath Basin. Some ranchers feel screwed by the decision – and compelled to return to the negotiating table.

June 2013 – As another drought grips the region, the Klamath Tribes exercise their newly recognized water rights to keep water in lakes and upper tributaries for fish habitat. The federal government also exercises water rights, and hundreds of junior water users are again cut off, spurring a new round of negotiations.

March 4, 2014 – The Klamath Basin Comprehensive Agreement is signed. Together with the two 2010 agreements, the document becomes the basis for forthcoming legislation.

May 21, 2014 – Democratic Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, of Oregon, and Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, of California, introduce legislation to implement the revised Klamath River agreement and begin dam removal. Committee hearings begin June 3.

This article was originally published on June 4, 2014, in High Country News (hcn.org). The author is solely responsible for the content.