“IN the depths of a limestone cavern, near a doorway to the Maya underworld, Filomeno Tomay took out a flashlight and held it up to the cave wall. . . .”

Thus begins my story in last Friday’s New York Times, which describes a subterranean Mexican adventure I undertook two months ago on the Yucatán Peninsula, where a unique geology has formed a subterranean universe of caverns, karst tunnels and sink holes called cenotes, some hundreds of feet deep.

Trim the jungle down to its roots, scrape away 10,000 years of sediment and mud, and the northern Yucatán is a billion-hole brick of porous stone, flat as a tortilla with hardly a lake in sight. Rivers are practically nonexistent.

But cenotes (pronounced say-NO-tays) dot the jungle by the thousands, and explorers can still dive down to document skulls, pots and artifacts untouched for hundreds of years.

Travelers to the Yucatán snoop and swim in dozens of managed cenotes, snorkeling or spelunking alone or with guides all over the peninsula. Parks near Playa del Carmen, Valladolid, and Tulum have cenotes open for swimming, as tourists and locals take cooling dips together in pools of deep spring water.

In late November, as the Yucatán experienced an unusual spell of cool weather, I boarded a second-class bus in downtown Cancún to begin a trip inland and underground, a half-dozen cenotes on my itinerary.

This story follows my cenote adventure, including a peek into five formations in the central part of the peninsula.

Read the whole story here.

See my photos from the cenotes trip below.

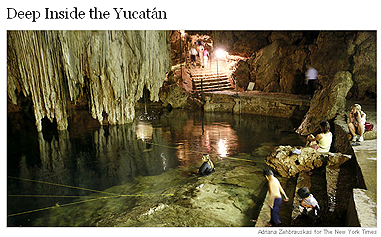

Cenote Dzitnup outside the town of Valladolid is essentially an underground lake. Thousands of cenotes, which are like sinkholes, dot the entire Yucatan Peninsula.

At the Convent of San Bernardino de Siena (above), a 16th-century Spanish monastery built atop a cenote, the founders strived to create a self-sustaining community with sequestered vegetable gardens, an orchard and water below. I visited one afternoon for a look into the monastery’s watery depths, now capped with a grated well.

Pretty light at The Church of San Bernardino.

Even Chichén Itzá—the famous Maya metropolis of pyramids and temples—rose from hardscrabble jungle at the edge of three cenotes. The cenotes were the foundation of the city’s infrastructure, wells that sated its thousands of citizens.