Fritz Barthel almost killed himself skiing on Mont Blanc, and it gave him an idea that would change his life and backcountry skiing forever. Today, almost all backcountry skiers and ski tourers use the invention he designed after that life-altering adventure.

The Austrian and a friend had just finished a rock climbing trip on the Mediterranean coast. It was the 1970s, and he was still in college studying mechanical engineering.

The two casually decided to ski Mont Blanc on their way home, but Barthel said they were dangerously unacclimatized, having come from sea level. Even using the tram, it took them a long time to summit, and they arrived bone-tired after dark back in Chamonix.

“That was one of the most exhausting days of my life,” Barthel recalled in a conversation with GearJunkie. The pair’s youthful gusto had gotten them into a rather dangerous situation. They’d been unprepared; their gear had been inadequate and far too heavy, Barthel thought.

“What could have been my reaction to that?” he asked. “I could have trained more to be in a better shape. But this was not really an option for me, as I’m a very lazy person. I thought, driving home from Chamonix from this adventure … I have to find some solution.”

That solution came to Barthel in the form of the revolutionary toe-pin binding system that both professional and recreational backcountry skiers use today. The principle behind Barthel’s “Low Tech” binding has become the global standard for backcountry ski touring setups.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Barthel patenting his design. GearJunkie caught up with the inventor from his home in Austria to learn more about how this system came to be.

Beginnings of the Toe-Pin Binding: ‘Low Tech and Incompetence Unlimited’

Barthel didn’t receive international praise for the toe-pin binding system overnight. In fact, his Low Tech design was rejected over and over again by one ski manufacturer after the next.

“I still have all the rejection [letters] of all the companies,” Barthel said, looking around his desk. “There was no official interest.”

The touring bindings of the day used a plate or frame that was attached to the boot and hinged on the toe piece. That allowed the heel to lift for uphill travel. It’s not dissimilar to some modern systems like the Tyrolia Ambition 10 B95.

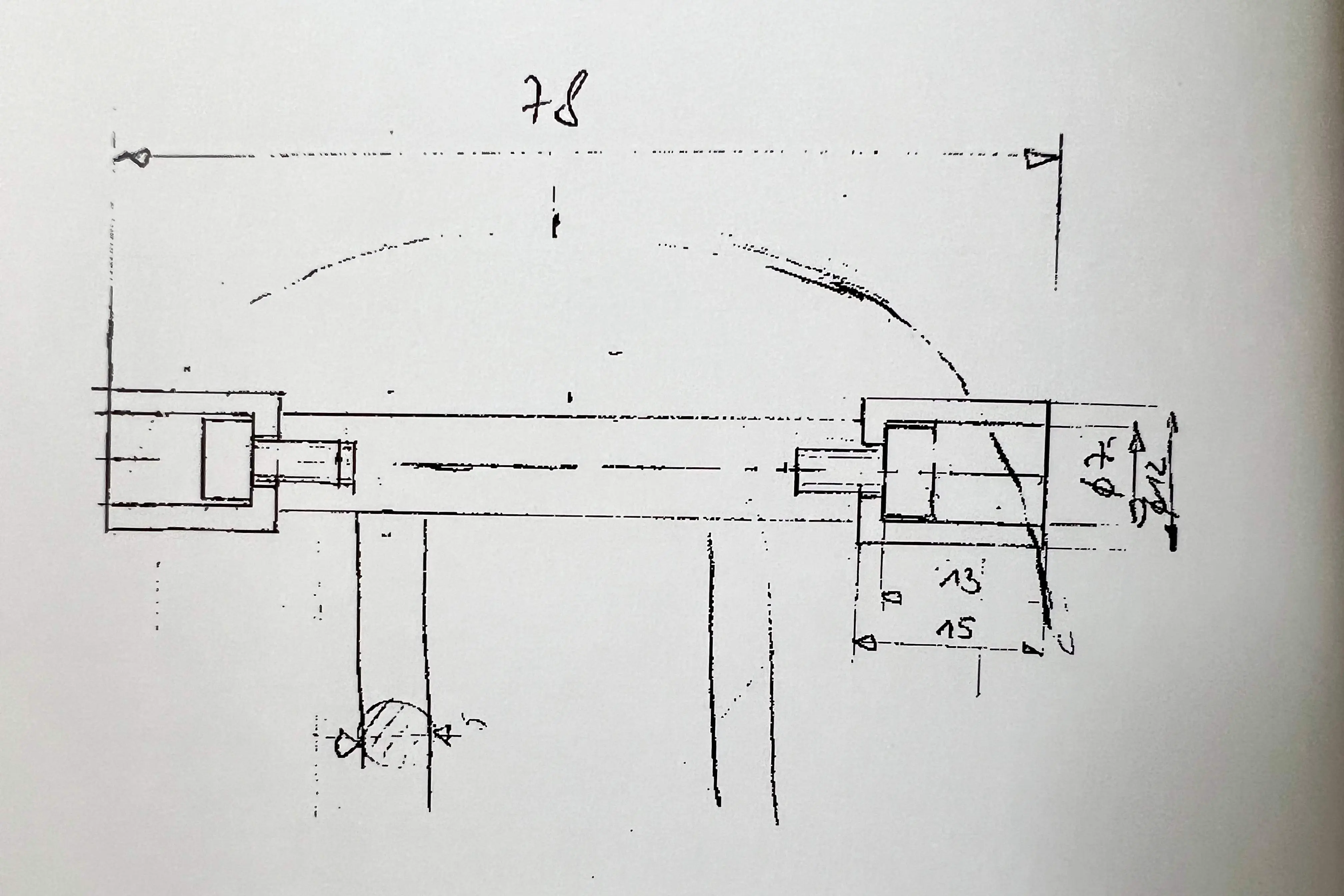

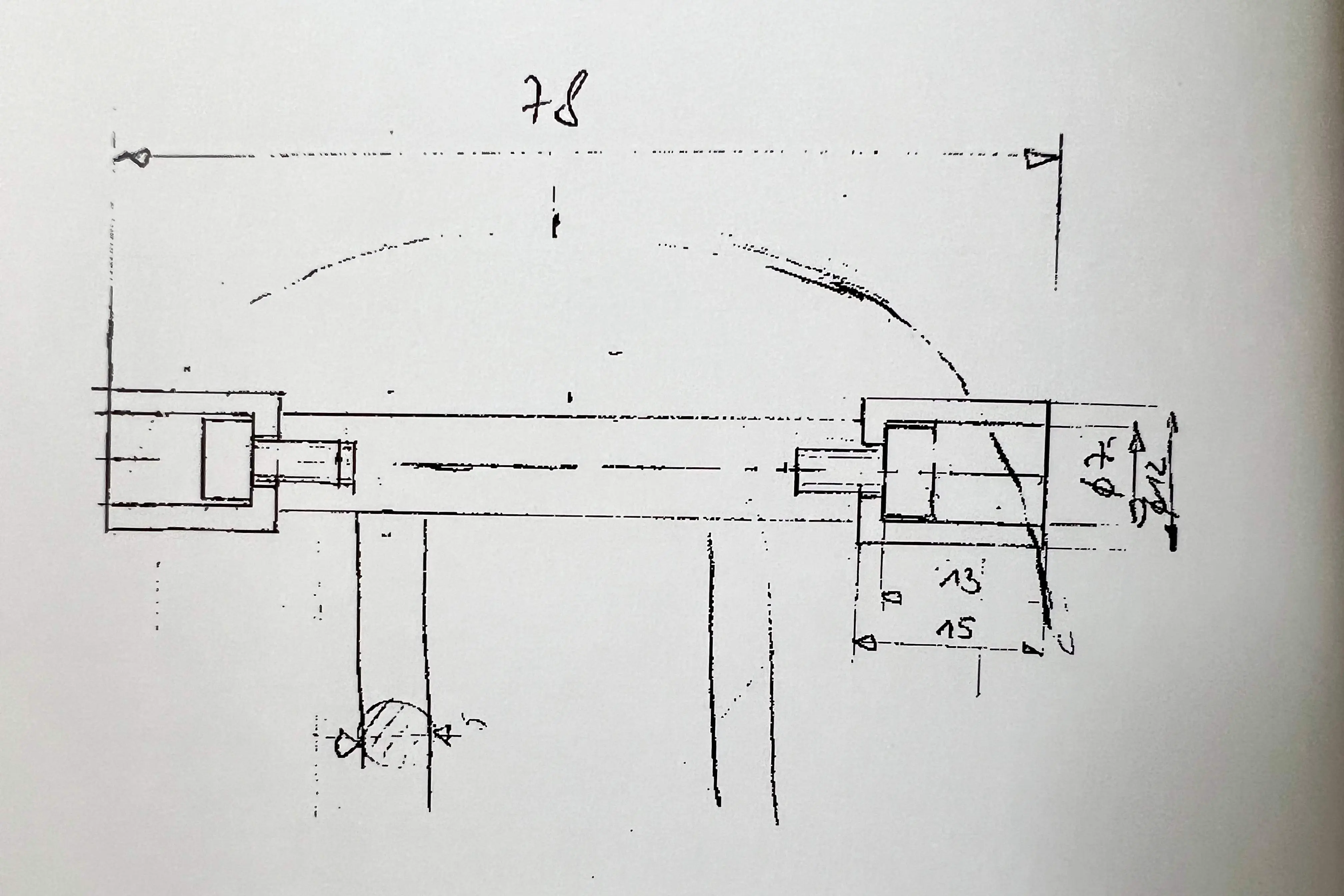

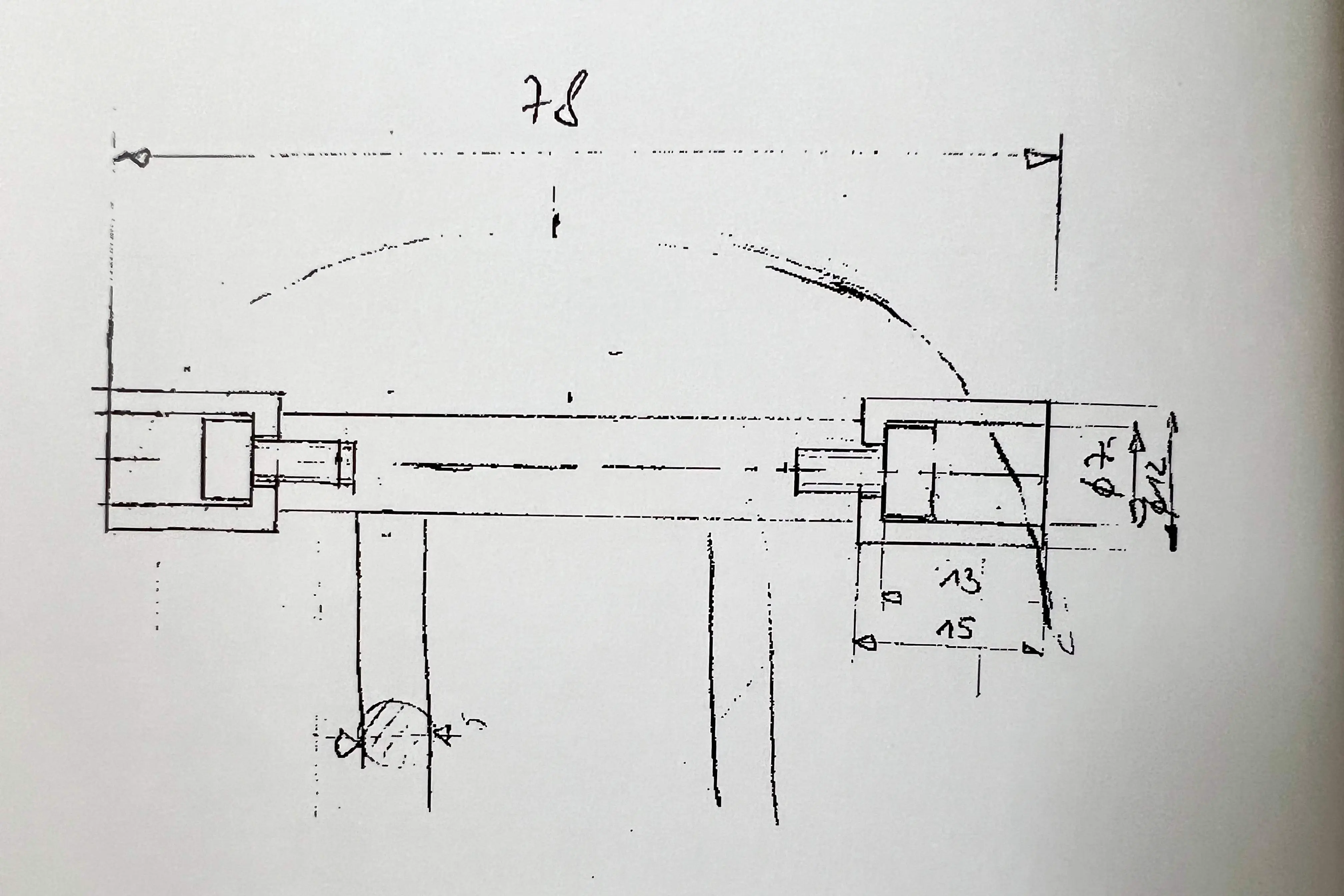

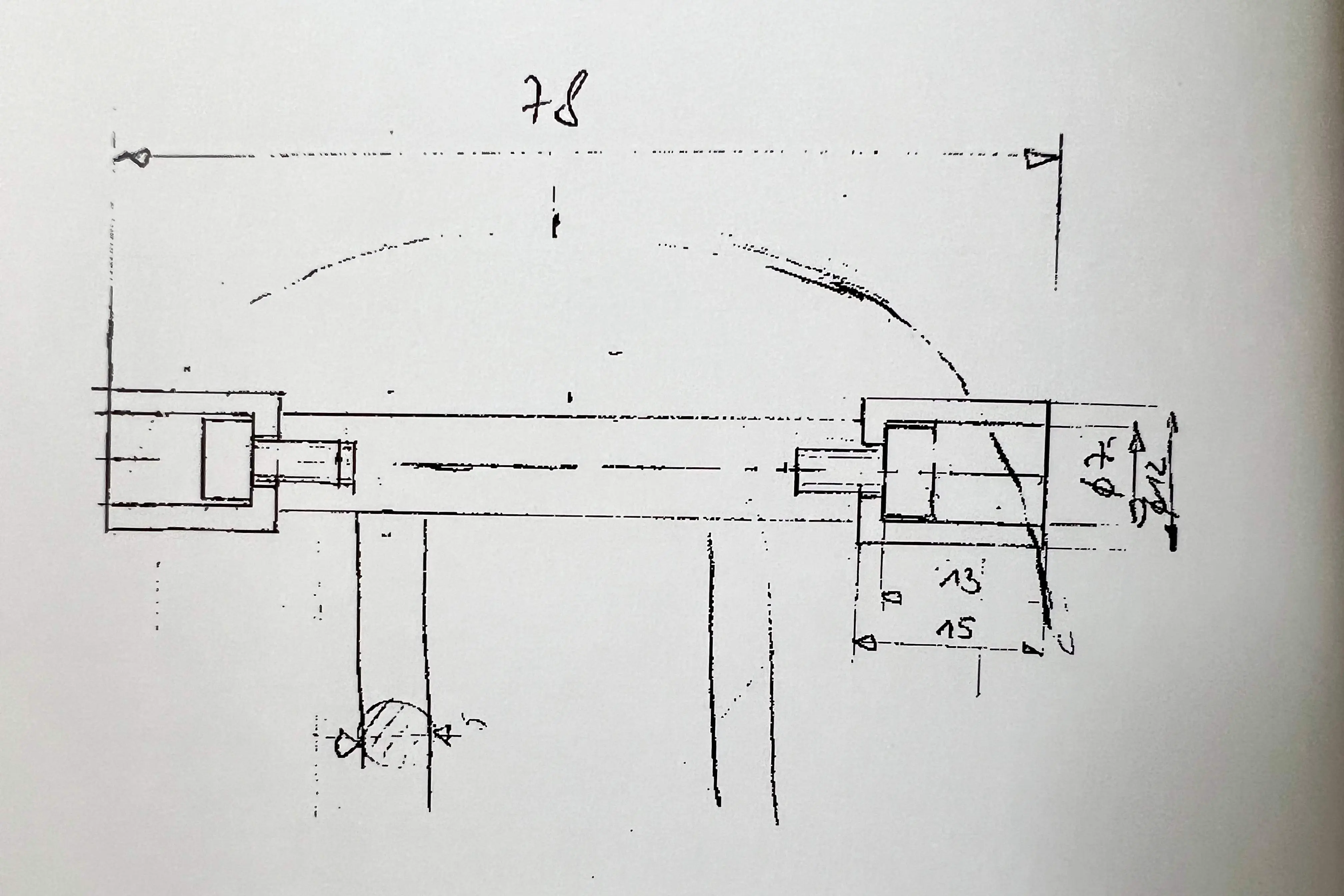

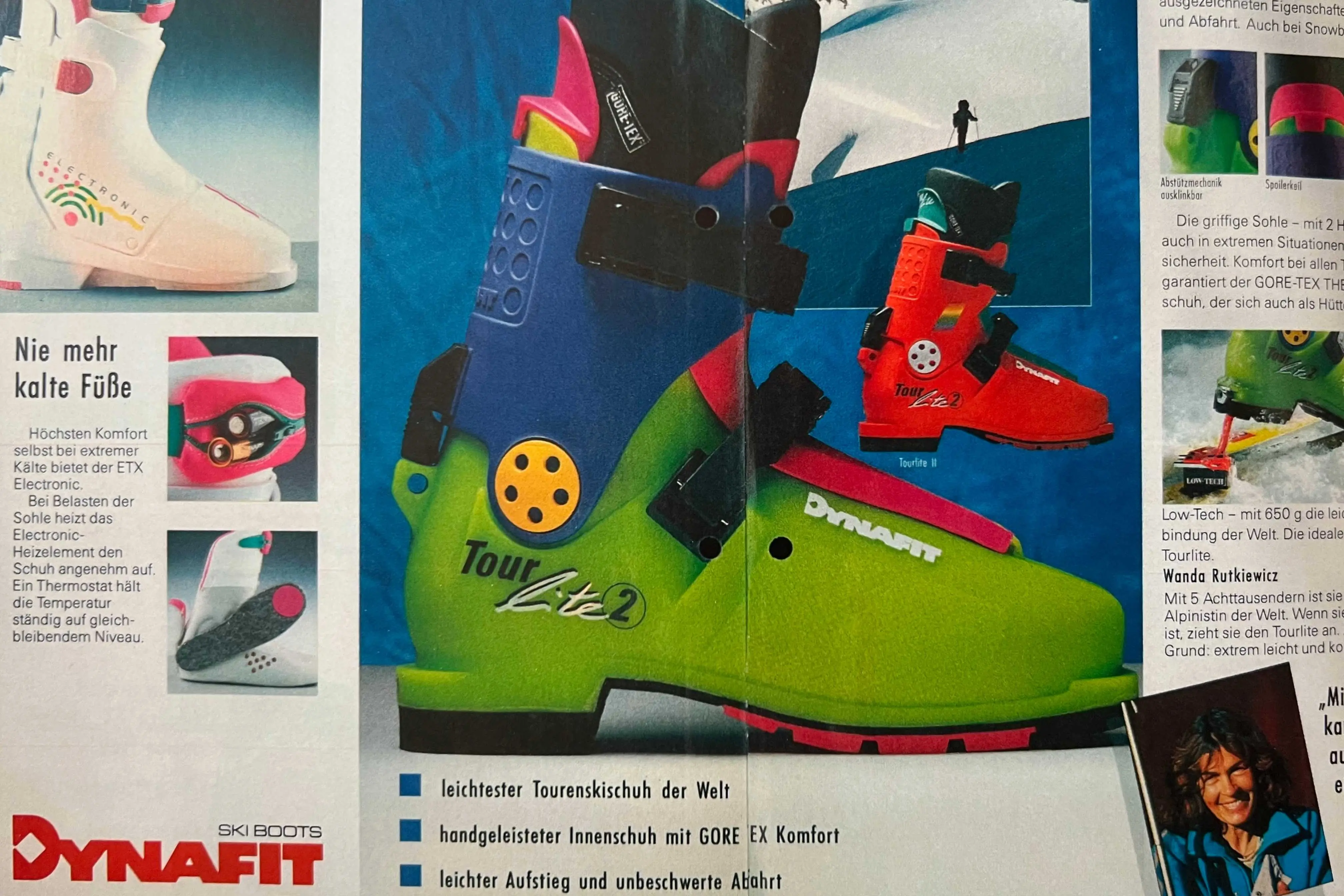

Barthel’s design, by contrast, was minimalist. It relied on toe and heel binding pieces with small pins and slightly modified plastic shell touring boots, which were relatively new.

“Compared to the leather boots, [the plastic boots] were super stiff. And so this very, very simple, basic idea came to my mind,” Barthel said. “Why not substitute the binding frame [with] the boot itself?”

He decided to name the design “Low Tech” despite all the outdoor products being marketed as “high tech” at the time. In 1984, he said he applied for a patent as a joke. Much to his surprise, he got one. Patent #376577 arrived in the mail from the Austrian patent office that December.

That’s when he started making prototypes and going to ski manufacturers — companies like Salomon and Tyrolia. The businesses all rejected him. However, his friends who tested the prototypes were excited by the design and gave him good feedback.

It inspired him to push forward despite the lack of interest he was facing from manufacturers. In fact, Barthel was so determined he even printed out business cards. They read: “Low Tech and Incompetence Unlimited. Fritz Barthel, President.“

Catching On in the Right Circles

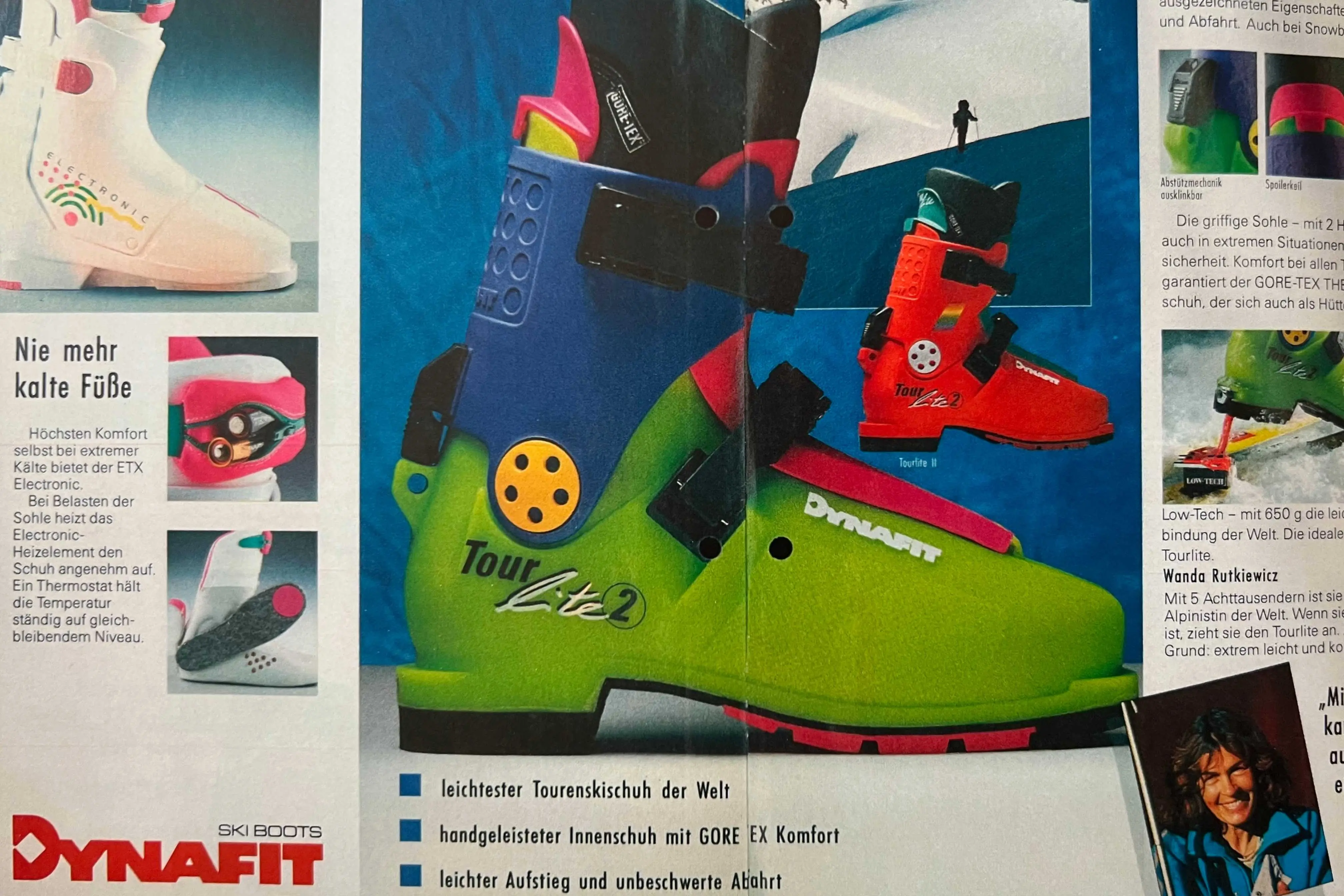

Barthel eventually convinced Dynafit to manufacture Low Tech toe pieces for its boots. The brand made him purchase the boots up front. Then Barthel was milling the heel pieces at home and selling them out of his basement (a workshop that he and Eric “Hoji” Hjorleifson affectionally called “the Dungeon”).

But that proved to be a challenge. Touring was, and still is, a niche sport. The customer pool was small in the ’80s, and the Low Tech setup required people to purchase new bindings and boots. His first few shipments didn’t move very fast.

But when some Italian racers saw Barthel’s Low Tech setup in the Chamonix Ski Rally, things started to change. They instantly recognized how beneficial a lighter, more minimalistic touring binding was for racing.

“Two weeks after, [some Italians] were showing up at my house,” Barthel recalled, chuckling. No one spoke the other’s language, but the message was clear: the Italian athletes wanted Barthel’s Low Tech setup.

“After that, this thing exploded,” Barthel said. “[Athletes] immediately knew the benefit or the advantage of this thing. So they spread it immediately in those circles.”

It was a smash hit on the race circuit in Europe, particularly among the Italians. It wasn’t long before Low Tech bindings were racking up wins in some of the most high-profile European ski races.

But Barthel wasn’t out of the woods yet. In fact, things were getting harder for him. As more orders came in, his home overflowed with over a thousand boot boxes, stacked “from basement to attic,” he described.

Eventually, it got to the point when he, his wife, and their child had almost no living space. Barthel was still individually milling every heel piece by hand downstairs in the dungeon. Despite the underground success he was seeing, there was still not a single ski manufacturer taking him seriously./

“It was at this point I was considering giving up,” he said.

‘Just Low Tech’

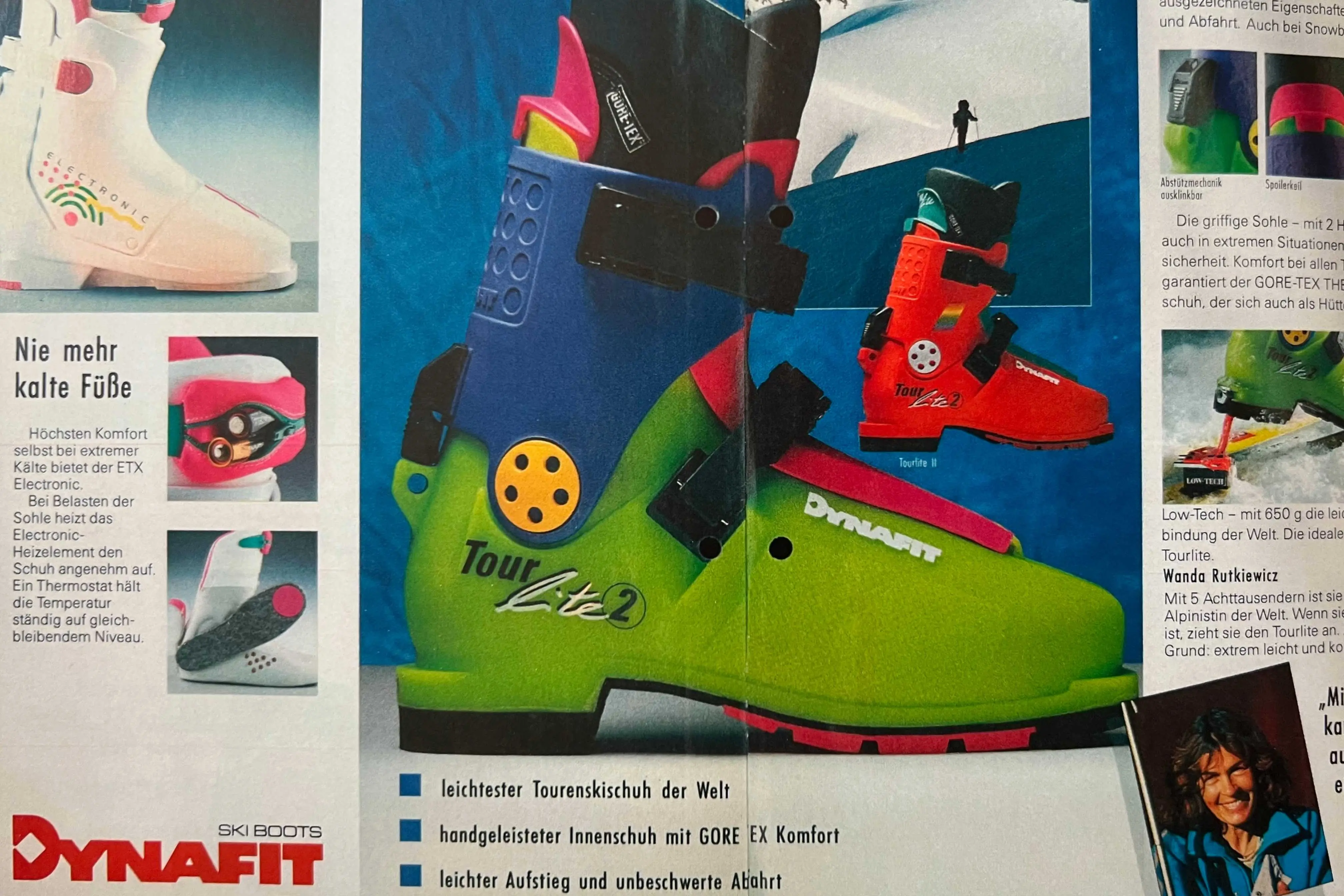

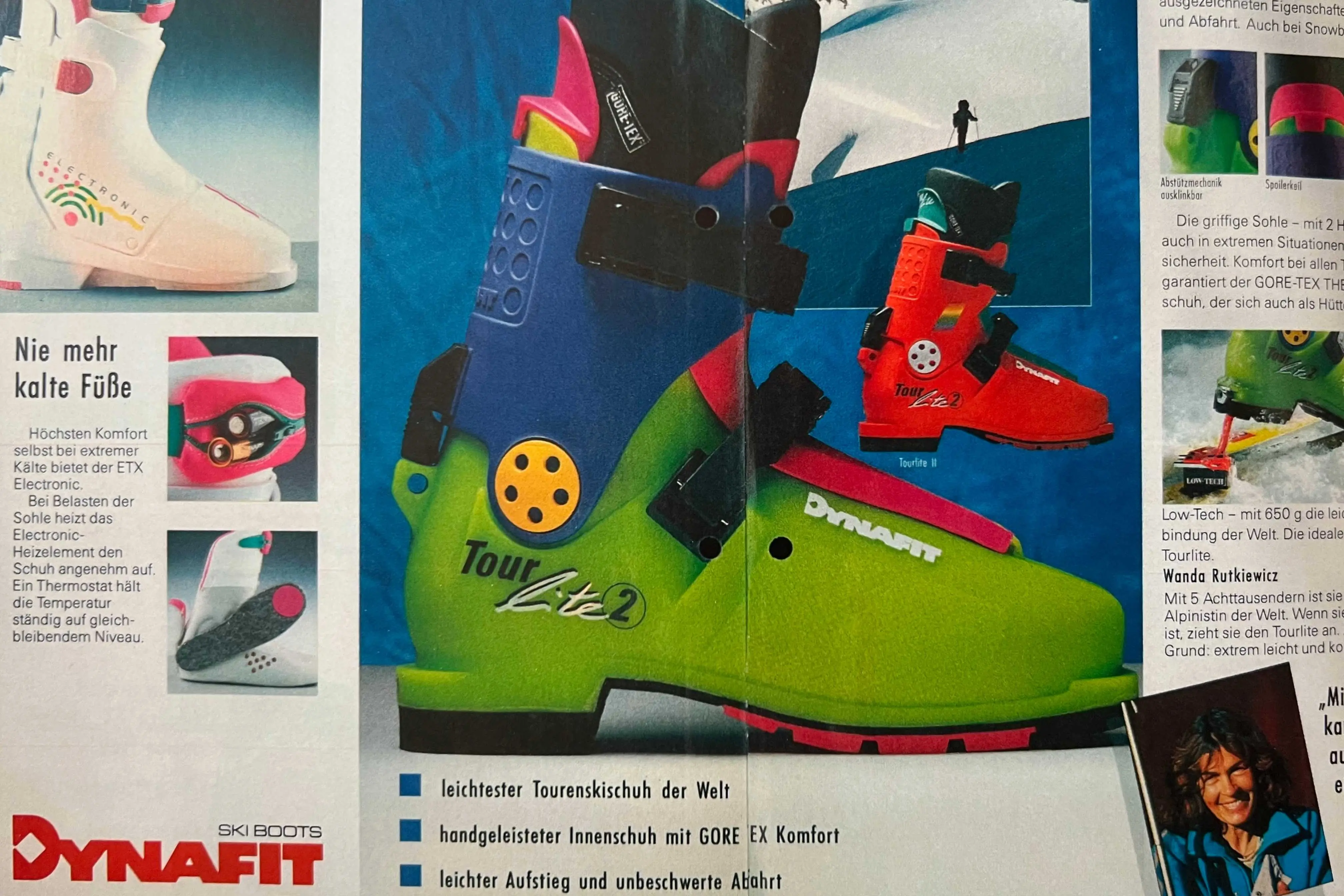

Luckily for the world of backcountry skiing, Barthel held on. Eventually, in 1989, Dynafit gave in and signed a contract with him to produce and sell his Low Tech binding and boot system. The first Dynafit integrated boot/binding system was launched in 1991 — the Dynafit Tourlite with the Tourlite Tech binding.

It became a flagship (although still niche) product for the brand. Over the next decade, Dynafit grew to become the leader in tech binding innovation. Ski racers continued winning races on Barthel’s tech setup.

But the Low Tech design was about to reach an even greater level of popularity. In 2006, his patent for the Low Tech prototype expired. Suddenly, every brand, not just Dynafit, could make its own version of tech alpine ski bindings. This time, ski manufacturers didn’t hesitate to jump on Barthel’s design. Very quickly, different brands across the industry started offering their own tech bindings.

Today, almost 70% of alpine touring bindings sold on the market are direct descendants of Barthel’s original design. Tech bindings have become ubiquitous in backcountry skiing and ski touring. Yet Barthel shook his head and laughed when I tried to emphasize Low Tech’s legacy in this sport.

“Don’t oversell it,” he said. “It really is just low tech.”

The photos in the article were used with Barthel’s permission from the book 30 Years of Dynafit Tech Bindings. If you can find that book, it is an amazing deep dive into how Barthel’s bindings developed under Dynafit and how the brand has innovated on the same basic design for over thirty years — and the visuals are fantastic.