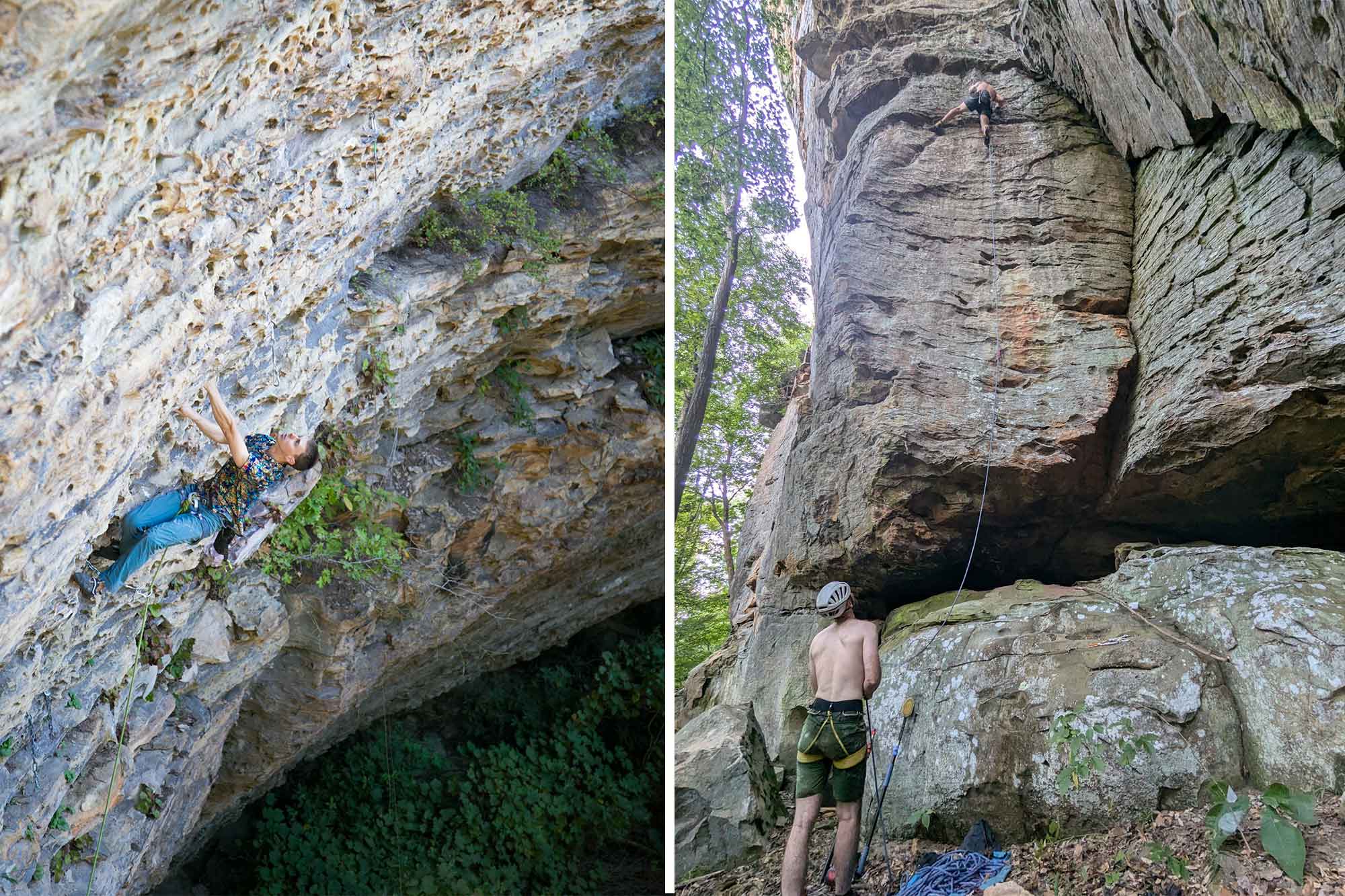

When 24-year-old Greta Staggs first started her job as a climber steward, she admits to feeling a little nervous. She was one of two people hired by Access Fund, a nonprofit that protects climbing areas, to spend this spring helping climbers at Kentucky’s Red River Gorge.

Every morning for several months, Staggs waited at various entrances to the canyon to speak with climbers coming to sample the canyon’s wealth of sandstone sport routes. Her job was to lay down the rules: Keep your dog on a leash to prevent accidents. Don’t climb after rain to avoid damaging the routes. And leave behind the hammocks, which increase erosion by encouraging people to walk off trail.

“You have to understand the different rules and regulations,” Stagg said. “When people have bought land for people to climb on, it’s important to respect that.”

The Red, as it’s known among rockhounds, is one of the country’s most popular crags. And it’s a key example of why Access Fund now hires people like Stagg to educate climbers on best practices. Like many U.S. climbing areas, Red River Gorge weaves through state, federal, and private lands. This results in different rules depending on which wall you’re climbing.

As rock climbing explodes in popularity, maintaining access to areas like The Red often means educating climbers, land owners, and politicians, according to leaders at the Access Fund and local climbing organizations. It’s now a streamlined playbook for protecting beloved crags — and one that seems to be working.

Deals With Landowners

If you want to protect a climbing area, the easiest way is simply to buy it. But it’s not cheap to permanently own and manage expensive real estate just for climbers.

Instead, climbing advocates increasingly rely on goodwill — and creative thinking. That’s what happened in 2020 when landowner Ian Teal contacted the Red River Gorge Climbers Coalition (RRGCC) about donating land. As the owner of Cliffview Resort & Lodge, he could offer the climbers access to more undeveloped rock walls. Once they developed nearby routes, Teal would benefit by offering nearby recreation to the guests of his cabins.

Negotiations continued for 4 years until this summer when the RRGCC announced an easement agreement with Teal. The organization’s leaders said the move allows for additional climbing access without the full cost and burdens of ownership. This is especially true since Teal will help develop and maintain trails in the area. The new area should open to climbers by fall 2025.

“It sets a solid foundation for future talks with other landowners in the area who may be interested in opening their properties for rock climbing,” said Billy Simek, RRGCC’s executive director.

RRGCC has existed since 1996, and the group has repeatedly bought land in the gorge to safeguard it for climbers. Simek said this has become a blueprint for climbing organizations, which often partner with Access Fund to purchase climbing areas. The nonprofit has helped buy nine sport climbing crags over the last 20 years.

That’s an expensive trend to maintain with the ever-ballooning prices of U.S. real estate. Instead, RRGCC hopes to find more landowners who are willing to let climbers do their thing. However, many landowners want extra assurance they won’t be held accountable if a climber gets injured on their property.

That’s why climbing advocates have started lobbying elected officials to give the sport greater legal protections. So RRGCC and the Access Fund have also started exploring another angle: adding climbing to the language of each state’s recreation use laws.

Educating Politicians to Save a Climbing Area

Climbing has come a long way in the last 10 years. After decades outside mainstream awareness, it’s now an Olympic sport, an Oscar winner, and a Red Bull favorite.

But it’s safe to say not everyone got the memo. In September, the RRGCC convinced State Rep. Timmy Truett, whose district includes part of the gorge, to check out the climbing at Red River Gorge. Truett had “no idea” that the sport had become so popular or that one of the best spots in the country was in his own district. A 2020 economic assessment from Eastern Kentucky University found that climbers spend $8.7 million in the area every year.

“At some point during Covid, I heard the term ‘bouldering’ and had no idea what it was,” Rep. Truett told GearJunkie. “That’s when I found out that we had something that everybody wanted, and I really had no idea. So we need to do a better job of educating our people about this hobby. In my opinion, anytime we can bring people to our region, it’s a win-win for everybody. I am hoping that we can schedule an event this fall to invite all legislators and their families to learn about and enjoy this sport.”

Truett’s support will be crucial as the RRGCC works on its next big goal. The RRGCC wishes to add climbing to Kentucky’s recreational use statute.

Every state has laws about recreational use that limit the liability of property owners. Some states specifically reference climbing in recreational use statutes — but most do not, according to the Access Fund. By explicitly adding rock climbing to the statute, lawmakers can ensure that landowners are free from liability when opening up their property for climbing.

Lobbying efforts from Access Fund and climbing groups successfully pushed for the addition in Texas and Washington. However, many other states still leave landowners liable, according to the American Alpine Club. Even Colorado continues to struggle to solve its land access issues.

But Truett said he doesn’t see any obstacles to adding rock climbing to Kentucky’s recreation use statute. Like the climbers themselves, Truett said it’s all about education.

“I think their plan is doable,” Truett said of the RRGCC. “We need to educate both climbers and landowners. Climbers need to know where they can climb and where they can’t. Landowners need to know that when they allow someone to use their property, they are protected from lawsuits. If we can ensure that these things happen, then we all will benefit from these collaborations.”

Access Fund and Local Groups Manage Climbers

When climbers showed up to The Red this spring, many of them found Staggs waiting to greet them.

She doesn’t just educate newcomers about the area’s rules. Staggs also manages the increasing number of rockhounds coming to sample the gorge’s wealth of sandstone sport routes. Each morning, Stagg could usually be found at one of the various entrances, offering coffee, snacks, and advice.

To reduce overcrowding at the gorge’s most popular walls, she started a “crag counter.” By using a whiteboard to tally up the climbers at hot spots, she could direct people to other walls and reduce the impact on the area.

“It allows other people to change plans at the parking lot instead of arriving at the crowded wall and getting frustrated,” she said.

She also makes sure that climbers understand proper etiquette, asking questions like: What does it look like to have music at the crag? How do we approach a crag? How are we treating the rock with our gear?

“We’re not there to create shame or blame, but to make people feel empowered to make these decisions themselves,” Staggs added.

Although some people take offense, thinking these efforts are “policing,” she said the overwhelming majority are stoked that Access Fund offers the Climber Steward program. In fact, many of them often say, “My local crag is seeing all these issues, too. Why aren’t you guys there?”

Staggs tells them to check in with their local climbing group and ask how to help. If climbers want to protect their favorite local crags, they can join clean-up days, help with trail maintenance, or boost fundraising initiatives.

“What the Access Fund and other groups are doing, it’s a really unique way to get people to start to think critically and learn more about the places they’re climbing in,” Staggs said. “When you are there in person, they are so much more likely to have the point stick.”