In an unassuming industrial park on Portland’s working-class northwest side, Chris King Precision Components cranks out bike parts. The little company counts fewer than 100 employees, but has nevertheless carved its name in bedrock among cyclists.

Since 1976, Chris King has made nearly indestructible components — at a low-waste manufacturing standard unmatched anywhere in the industry. What started when the company’s namesake founder discovered a way to salvage landfill-bound, medical-grade bearings became a fabrication model that’s laser-focused on limiting waste.

It hasn’t always led Chris King straight to fatter bank accounts, as general manager Kirby Bedsaul will tell you. Acting for good often means sacrificing profits. (Even a group of MIT researchers acknowledged that businesses must make adjustments to the “price mechanism” if they plan to prioritize ethics and still survive.)

King’s balance sheet may not scroll as deeply as Trek’s or Shimano’s. But one thing it can claim? A factory that’s one of one, painstakingly designed for resource circularity.

Yet the facility’s unique nature is exactly what hurt King in a recent bid to recertify with business ethics auditor B Lab as a “B Corp,” or Benefit Corporation.

It’s worth noting that a company can legally register as a Benefit Corporation without interacting with B Lab. By meeting requirements that vary from state to state in metrics like transparency and mission, any company can become a Benefit Corporation without being a B Lab-certified “B Corp.” Ostensibly, however, the certified labeling carries more weight with the average consumer.

King may operate the most environmentally friendly plant in the cycling industry, and it may have envisioned a sustainable model before the concept of “sustainability” pulled any weight in just about any industry. But does it pass muster with B Lab, where registered companies “do more than make a profit. [They] prioritize people and our planet in everything they do”?

No.

And here’s the thing: Chris King can only speculate why. Because, according to the company, B Lab failed in communication.

Chris King did not provide documentation of its contact with B Lab during the companies’ recent months-long back-and-forth, but Bedsaul described a repetitive disinterest the nonprofit took in finding solutions to fit King into its model.

B Lab, on the other hand, responded to my emails by saying it does not comment on any company except those that currently carry the B Corp label (it also told Fast Company it doesn’t comment on individual certifications at all).

Meanwhile, criticism against B Lab has mounted for years. Where it was created to empower small companies with big ideas, some say it’s now a marketing machine with a fading mission — evinced maybe most searingly by its 2022 certification of Nespresso, the Nestle subsidiary that had come under stringent worker abuse allegations, including but not limited to child labor.

All Chris King wanted to do was improve on its already cutting-edge factory processes.

Chris King Components: One of One

“We were hoping to work with B Corp on a set of manufacturing standards, to move beyond the basics of transparency and domestic materials sourcing, but after a lot of back and forth with B Corp and B Lab, it seems they don’t have the bandwidth to establish manufacturing standards that reflect the depth of what we’re doing at King,” Bedsaul said in a press release when King gave up the ghost.

“The B Corp movement is important, and we have learned a lot from the process of looking at all our business practices,” Bedsaul continued, but “forgoing the certification to invest in what comes next feels like the right choice for us.”

A recent Instagram post offers a window into what the “depth” he’s talking about. All subtractive manufacturing produces scraps. For Chris King, many of them take the shape of tiny aluminum burrs and shavings.

High levels of aluminum, especially in aquatic ecosystems like the Willamette River (which is a stone’s throw from King), are not good for life on the planet.

On the factory floor, the toxic slivers accumulate as quickly as you’d think. How to deal with them? See below:

It’s the kind of process that has taken place at the company since its inception. The eponymous King knew he could reduce his footprint by acting locally, so he sourced his aluminum and steel barstock from the United States and never outsourced his labor.

When the company moved to Portland in the early 2000s, it built its plant around a one-off water cooling system. Around 3,000 gallons of water circulate throughout the building each day, heating and cooling offices and common areas as well as machines. King estimates the system saves about two-thirds of the energy it would need to pump into traditional air cooling to accomplish the same thing.

And the canola oil it uses to lubricate and cool its cutting tools? That’s a masterstroke. It’s more stable than synthetic cutting fluid, so it has a longer life cycle. And it’s far less hazardous to workers. The only drawback: You can’t cut as fast (i.e., make money as fast) with it.

Product manager Jay Sycip puts it succinctly in the video below. “The whole process is pretty slow going. We’re a rarity in the bike industry.”

Power in Transparency

If that all makes King sound like a company that does “more than just make a profit,” and thus could merit B Corp status, well, B Lab previously thought the same thing. The recent certification shortfall was not the brand’s first go-round.

Bedsaul initially decided to pursue B Corp certification as early as 2018, and King ended up earning the badge in March 2020. But B Lab uses a 3-year renewal cycle, and by the time King owed its re-certs, something had changed.

Bedsaul repeatedly told me King’s goal was to retain B Corp status. After all, its seal of approval had helped the company before. Getting a widely respected stamp of approval is a boon, especially when you’re operating in an unorthodox way.

“We initially said, ‘Hey, we want to stop beating our own drum, we want a third-party validation.’ We thought it made sense because we’d been doing it for so long, but sometimes people would come back with, ‘Well, how can we trust you when you’re the only ones saying it?'” Bedsaul explained.

Corroboration is a clear benefit for any company considering B Corp certification. The appearance of throwing the doors open and welcoming criticism means transparency — which, especially nowadays, sells.

Many B Corps leverage this narrative mechanism in their marketing and outreach.

Klean Kanteen has been on the list since 2012. Pull quotes from a company spokesperson included, “From the products we make to the nonprofit partnerships we forge and the way we show up in our communities, B Corps are on a mission to make a positive impact in the world. It’s about voting every day with small, personal actions. Living your values through your purchases and choices. Together we can change the world with the choices we make. It’s about asking: Who will I choose to B?”

Elsewhere, companies point to their own impact reports and internal vetting processes.

B Lab itself uses this technique. Its “B Impact Assessment” uses a points system that offers a snapshot — 80 is a passing score (“ordinary businesses” get a 50.9). The score is an aggregate of five categories, and what underpins them are audits that are relatively public. On B Lab’s website, you can find some documents filed by registered companies with titles like “Transparent Disclosures” and “Transparent Agreements.”

But those aren’t available for every company — Chris King, for instance.

The documents look more or less like standardized exams — checklists and questions with graded answers. Whether or not B Lab’s publication of them amounts to transparency is a matter of degrees.

Nespresso Gets Green Light

By contrast, documents Nespresso filed with B Lab are available. And they directly address the child labor concerns. The arm of the company implicated (Nespresso Global) discloses that it “identified three confirmed cases of child labour” on farms associated with it. And it took remediative action, such as hiring “dedicated social workers to support local families and reinforce Nespresso’s zero-tolerance child labour policy.”

Still, stats the company reported elsewhere don’t look promising in terms of workers’ quality of life. The reply field for the question, “What is the company’s lowest paid wage as calculated on an hourly basis?” is redacted with a box marked “sensitive.”

On the same page, the percentage of employees paid a living wage is marked “N/A.”

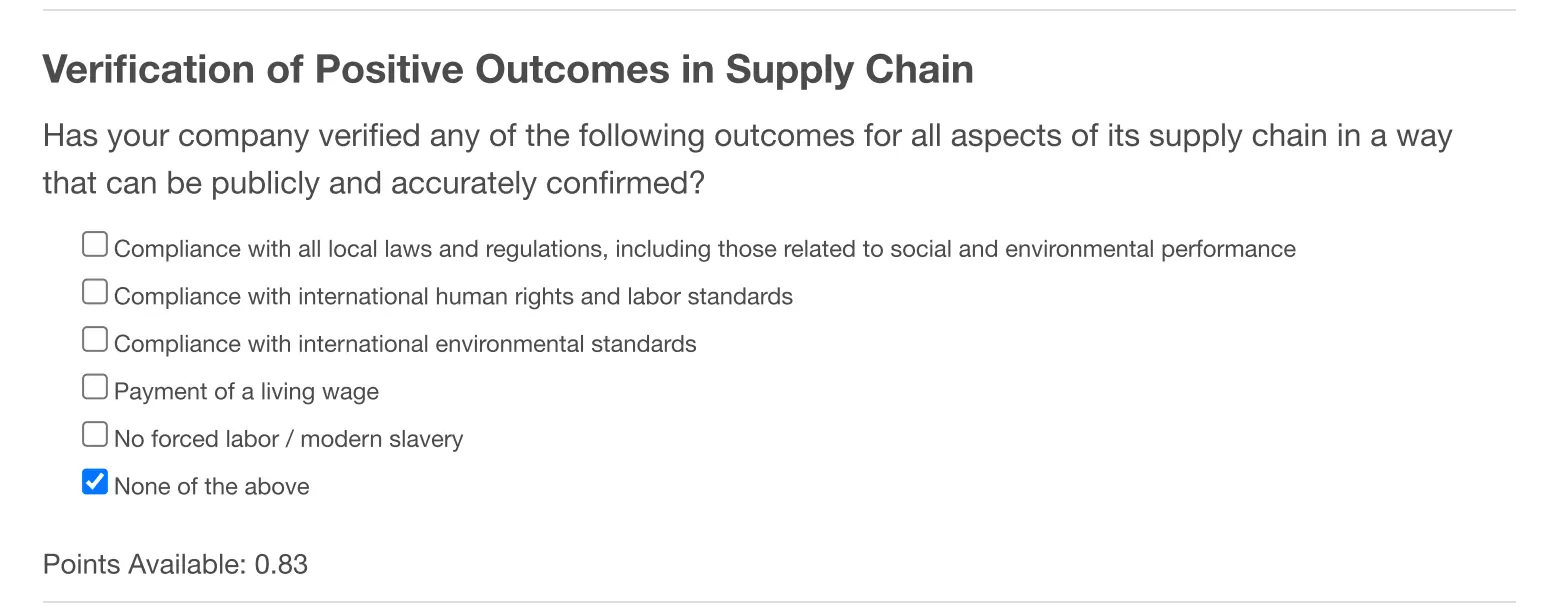

Elsewhere, you’ll find this:

Meanwhile, B Lab summarizes one of the company’s programs is actively “ensuring a sustainable supply of high-quality coffee and improving livelihoods of farmers and their communities.”

Nespresso Global earns a 93.6 overall score, plenty past B Lab’s certification threshold of 80 and notably stronger than Chris King’s 80.7. In fact, Nespresso Global decisively outperformed King in the “Workers” category, scoring 22.6 to King’s 17.2.

Remember how King protects its machinists from harmful cutting fluid? It also offers all its employees breakfast and lunch cooked by an in-house chef in exchange for biking to work.

The comparison here is not apples to apples. And it goes without saying that any impulse for a reduction in corporate-fueled child labor is a good thing. But you can see the frustration for a company like Chris King.

How is a mega-corporation accused of multiple human rights violations a “business for good,” but a small-scale manufacturer who built its own in-house recycling facility — at its own cost — can’t get a meeting?

You wouldn’t be alone if you passed the opinion that B Lab is creaking under increasing burdens.

Grow or Die

B Lab started in 2006. It was the brainchild of co-founders including two former employees of AND1, who left the company in disgruntlement over a corporate acquisition. The idea was to scale alongside the businesses it brought under its umbrella. That meant the nonprofit would guide capitalism itself, by steadily widening its scope.

Traction came immediately. B Lab certified its first B Corps, 82 “small and medium-sized” businesses, in 2007. Three years later, it was grabbing headlines as it lobbied states to develop tax structures for “benefit corporations.” (It would eventually succeed in 43 states.)

Today, B Lab counts over 5,700 registered B Corps; 90 are multinationals that report over $1 billion in revenue.

Insofar as B Lab exists as an extension of its portfolio, it faces no recourse but to engage with increasingly large corporations. As B Lab’s marketing and communications director Sarah Silverman pointed out to me, it couldn’t accomplish its stated objectives unless it swam with the sharks.

“A B Corp movement without the credible participation of large corporations will fail to realize its vision of a global economy whose purpose is to create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders,” Silverman said. She added that the “movement embraces the creative tension inherent in scaling better business.”

Klean Kanteen’s nonprofit outreach manager, Caroleigh Pierce, spoke to the utility of B Lab’s guidance as her company scales.

“We have a report card to guide our goals and a roadmap to keep us moving forward and always improving how we run our business and care for our people,” she said in an email. “It encourages us to make better decisions and holds us accountable to our community.”

Time Investment Skyrockets at King

Bedsaul, on the other hand, found B Lab cumbersome and formulaic in its corporate apparatus. The months-long period of interfacing revealed a pattern where B Lab repeatedly failed to focus on “solutions” for how to fit King’s evolving model into its evolving framework, Bedsaul said — even when he himself was bringing them to the table.

For instance, B Lab adamantly wanted to know how much water King saved on its polishing processes. The problem is, King didn’t know — because it’s never used any.

Thinking fast, Bedsaul contacted “friend” manufacturers in noncompeting industries, asking them for water consumption stats. To help tailor that information so it answered B Lab’s questions, he hired a consultant. Then King came back with that research, funneled down to its best estimates of its own water savings.

But in the end, Bedsaul wasn’t even sure it was worth sinking the resources into the inquiry. The trick, it looked like, would be accurately estimating how to score the most points where.

“[Answering] the questions just wasn’t straightforward, from a time and resource perspective. It seemed like you had to have somebody who understood the inside [of B Lab] to come back and say, ‘Okay, don’t worry about these questions, let’s go after this instead.’ So much back and forth about how you get to a certain score.”

Of course, your resources are sunk if you don’t meet the mark. It’s one incentive companies face when interacting with B Lab — once you start, it’s important to make it to the finish line.

So, King continued to work diligently toward finding a way to recertify. Work started to pile up, to the point that neither employees nor the special consultant had enough free time to do it. Bedsaul eventually faced the option of hiring a full-time employee who, essentially, would do nothing but interact with B Lab.

Silverman said the onus of labor Bedsaul reported does exist — but did not specifically relate it to Chris King.

“A company does not need to hire new employees or a consultant to navigate the certification process, though many find it helpful, especially large enterprises, multinationals, or those with complex structures,” she said. “We do advise companies to rally people from various departments, including legal, human resources, procurement, facilities, and leadership.”

A B Corp Success Story (With a Little Help): Rumpl

It’s not an uphill climb for every company that wants to affiliate with B Lab, and some do unlock benefits that go beyond quick impressions on customers at the point of sale. Rumpl is one such example.

The tiny company, which makes blankets, towels, and other soft outdoor gear, certified with B Lab in 2021. In its pursuit of the status, it was graced by an unexpected benefactor: a consultant who proposed to file its paperwork with B Lab for free.

Clay Young was an MBA student when he spotted Rumpl founder and CEO Wylie Robinson at an outdoor gear show. Young marched up to him with the pitch ready. Months later, Young had surged through the Impact Assessment, sourcing several different people within the company and performing all interfacing with B Lab.

“It was instrumental,” Robinson told me of Young’s work. “For things like our supply chain, we needed to get to a real granular level. There were a litany of concerns like that. And we’re between 20 and 30 people, so it can be a lot of work. For Clay to be the direct conduit to B Lab, it helped us a lot.”

Not only that, it fulfilled a personal goal Robinson had set for Rumpl from the outset.

“I’d been interested in becoming a B Corp ever since I started Rumpl. We got access to the whole community of B Corps, and their people were super hands-on with me once we got the certification,” Robinson said.

Broadly, Rumpl explains the influence B Lab has exerted on it as an improvement in its ethics. The Impact Assessment, it said, “highlighted some areas where we excel, and others where we came up short.” And echoing Klean Kanteen’s comments, it said it received “a clear roadmap to improvement.”

One key area of said improvement for Rumpl? Its supply chain. The company sources its raw materials from Asia. Facing questions over the distances between areas it’s active in and known conflict zones, for instance, was illuminating.

“In the first assessment, we didn’t really change anything [we were doing] — we were just documenting. So we learned a lot. We didn’t know where, exactly, these nodes in our supply chain were, especially relative to conflict zones. And now, those nodes have changed,” Robinson explained.

The research and communications components weighed heavily on the process, and recognizing an opportunity, Young parlayed it. He went on to co-found B-Certify, which exists solely to help other companies become B Corps. In all likelihood, though, he won’t have a repeat client in Rumpl — Robinson and his team expect the recertification process, underway now, to go smoothly.

“In the supply chain example, now that we’ve made those changes, it’s just ‘boom, check a box,'” he said. “Easy.”

Factory Visit Flops

Still, Young’s business model tracks on multiple levels. Checking B Lab’s boxes is arduous, sure — but knowing a company inside and out is key to conveying the bigger picture. Checklists and multiple-choice questions can quantify information, but they are famous for missing the overall point.

Bedsaul saw this discrepancy in Chris King’s case and moved on it. Knowing a human element would at some point be required, he took pains during the re-cert effort to make sure a B Lab representative visited the King factory.

Boots on the ground did eventually arrive, in the form of Wes Griffin, administrative director for B Local PDX. Griffin would tour the facility, and, Bedsaul hoped, loosen up the grinding gears that were otherwise threatening to seize.

Unfortunately, Griffin wasn’t exactly the man for the job. “B Locals” are essentially sub-units of the B Lab structure. As the name suggests, they’re localized groups, composed of B Corps and supporting staff that seek to grow the “movement.”

Griffin emphasized that he is not privy to the B Lab certification process. Some questions I asked him concerning the visit, he said, were “completely out of [his] purview.”

He toured King last October, only a few weeks after he started at B Local PDX, he told me. Here’s what he had to say:

“Kirby [Bedsaul] expressed pride in being a B Corp but concern that recertification would take significant effort and bandwidth. They showed me many of the creative factory solutions aimed at making it an efficient and green operation, and they said they felt like their [2020] B Impact Assessment score didn’t reflect how ahead-of-the-curve many of these practices were.”

Griffin concluded that he found “only positive things” to say about King and the company’s “impactful” work.

But the visit, and any report of it that Griffin may have delivered to B Lab corporate, didn’t matter where it counted — or not enough. And when representatives suggested King purchase carbon offsets to make up for the shortfalls, Bedsaul pushed his chair back from the table.

“That’s when I said, I’m done,” Bedsaul recalled. “I didn’t have the energy left for it at that point, and I felt like we’d just stopped seeing eye to eye.”

Carbon Offsets? No, Thanks

Asked whether B Lab typically advises companies to buy carbon offsets to boost their environmental scores, Silverman provided an answer that did not mention the term.

“The B Impact Assessment awards credit for specific, positive practices of companies to determine their eligibility for the certification, but does not require that companies have specific practices in place,” she said.

B Lab is strongly focused on citing improvements and progress in the companies it certifies, so it’s possible that it cruised Chris King with the offset proposition due to that. Silverman called B Lab’s standards, “a framework for enhancement,” and its “theoretical” stated goal is to “transform the economic system.”

Every Man Jack, for instance, earned its B Corp status just this April. A concomitant announcement on its website listed sustainability goals it hasn’t met yet, like reaching “100% sustainable” packaging by 2025 and making “aggressive” reductions in water, electric, and solid waste use along its supply chain.

Was Chris King penalized for operating on the same, sustainable platform for 20 years and not planning to change it? Maybe. But since B Lab doesn’t comment outside its current stable of companies, there’s no way to tell.

King sensed this could be a problem, so Bedsaul eventually approached B Lab with another idea: to help the nonprofit develop a new set of manufacturing standards other manufacturers could use. Bedsaul is not alone in his evident cynicism of the carbon offset market. And as a small company, it’s understandable to want to bring impacts under your own roof.

“It just felt like they weren’t very interested in finding solutions with us this time,” Bedsaul assessed. “And I get it — not many companies are doing things the way we are. But we believe, based on what we’ve seen ever since Chris started the company, that any manufacturer could scale and implement our processes, and see improvement.”

According to Bedsaul, he was prepared to throw open the doors to directly competitive titans; he mentioned SRAM and Shimano.

Still, the proposal died on the table. That’s despite King landing a massive score on its 2020 certification for its “Environmentally Innovative Manufacturing Process.” Of course, as Chris King is no longer an affiliated company, Silverman could not comment on the matter.

B Lab Faces Giants, Dicey Future

It’s intuitive that Bedsaul would offer to help inform B Lab’s standards, because the nonprofit more or less constantly re-evaluates them. Fast Company noted the nonprofit has already revised the B Impact Assessment six times. Its current “review” of standards started in December 2020, and the most recent progress report on it, published this month, is 64 pages long.

Late this year, it will hold a round table where “all interested stakeholders” will provide “final” feedback — on protocols that may still need “further development.”

The goal, as the spokesperson put it, to drill down on “approximately ten specific topics” and “ensure that B Corp Certification remains a differentiation of high-performing companies using business as a force for good.”

However much labor B Lab pours into its processes behind the scenes, though, the optics will always be splashier on the shelf (and thus at the cash register). Picture the average millennial or Gen Z shopper cruising the shelves, anxious to make a conscionable purchase but strapped for time and cash.

It’s easy to see how the circled “B” emblem can drive sales.

Will B Lab force (or help) the megacorporations it now interacts with to fall in line with its values? Its recent track record reveals some steep challenges.

Nespresso is not alone among B Corps that have come under heavy fire for recent worker rights violations. Widespread complaints of dangerous working conditions at Scottish brewery BrewDog surfaced in 2021, and Teamsters leveled a complaint against organic food giant Amy’s Kitchen for worker exploitation.

Both, like Nespresso, remain B Corps.

Under these circumstances, can we say B Lab is a “movement?” Or just a clearinghouse for greenwashing?

For most of us, any heat a company faces under the magnifying glass of B Corp certification is a positive. But on the other hand, it’s discouraging that it would turn its back on any company demonstrating a baseline of responsible action.

For its part, King stated it will remain a “Beneficiary Corporation with all the transparency requirements” that come along with it. (A quick investigation by AllGear’s legal team revealed that Oregon state law requires all Benefit Companies to adopt some third-party certification standard — of which there are several. It’s unclear where King stands in the process.)

But the treatment Chris King received from B Lab, especially in light of its potential influence on an industry at large, will ultimately undermine B Lab’s “vision.” That, as Silverman put it to me, is to “create an inclusive, equitable, and regenerative economic system for all people and the planet.”

True, B Lab will never wield influence on a global scale unless it squares up with the actors that dominate it. But if it loses its soul, there won’t be much left to fight with.