Contributing editor Jeff Kish is hiking the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail this summer. This is his first report from the trail.

THE CONTINENTAL DIVIDE rose up from behind Glacier Park Lodge into air that was thick with smoke from the fires in Washington. It was morning, and I was hopping off the train in East Glacier to begin my thru-hike of the Pacific Northwest Trail.

I needed a backcountry permit to traverse the park, so I jumped on a shuttle to Two Medicine. The ranger station was a small brown shack by a lake that was surrounded by tourists who were waiting in line for a boat tour.

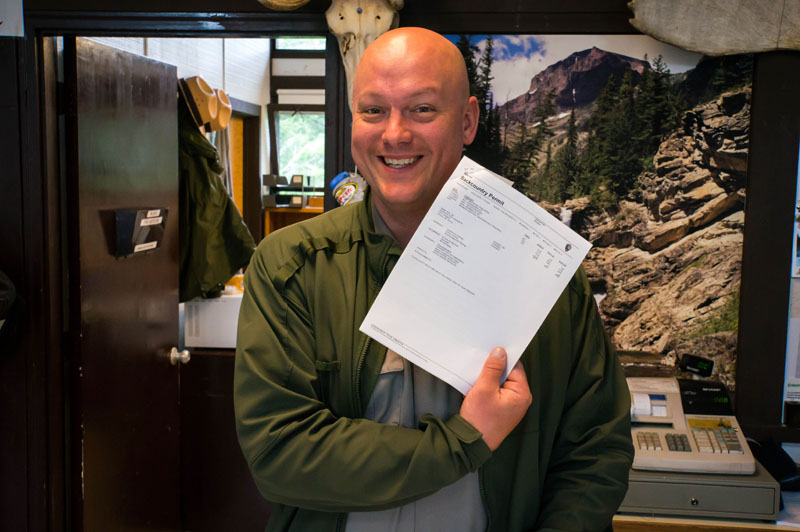

I explained what I was about to do and watched a video about backcountry safety while the ranger pecked away at a keyboard to generate my permit.

His name was Marc, and he was the first person to swim in all 168 lakes in Glacier-Waterton; a 10-year quest to raise money for a charity that lets kids with cancer experience the Montana Wilderness (read about it at Glacierexplorer.com).

Marc shook my hand, wished me well, and then with permit in hand, I got back on the shuttle to East Glacier.

It was a quirky little town. There was a Mexican restaurant with a hostel in the back, a bakery with a hostel upstairs, and another bakery that sold backpacking and climbing gear alongside their pastries.

I spent the evening with a crew of other travelers at the bakery hostel, and then I turned in to get rested for my first day on the trail.

The next morning, I boarded the shuttle again. This time I was headed for the end of the line: Chief Mountain Customs on the Canadian Border — the Eastern terminus of the Pacific Northwest Trail. (It’s also one of the northern terminus options for the Continental Divide Trail).

The driver’s name was Chris, and he had worked in the park 20 out of the last 50 years. I sat in the front seat and we swapped stories for the next few hours. He had some memorable quotes.

After I asked about shrinking glaciers: “Look! They’re just ICE CUBES! Remnants. It’s not like they are some endangered species that’s disappearing from the park. Ice melts. It’s nothing to cry about. The glaciers were melting in the 1960s, too. It’s just a ‘cause’ now all of the sudden.”

He continued, “Besides, tourists only ever see three of them anyway, because that’s all you can see from a car. So I don’t know what they’re worried about.”

After I asked about wild morels: “I had a friend that picks mushrooms. He made me soup once. I said, if that’s what wild mushrooms taste like, I’m sticking to Campbells!”

As we approached the Canadian border, he left me something a little darker: “Glacier and Mother Nature aren’t good chris-tee-ins, Jeff,” he said in his southern drawl. “They don’t forgive.”

And with that, I began my solo trek across the park.

With the images of bear and cougar attack scenarios fresh in my mind from the backcountry safety video, and Chris’ strange parting words, I wanted to get to camp before nightfall. I had to hike 14 miles in five hours, and I did just that.

Along the way, I encountered three day-hikers that warned me of a grizzly on the trail up ahead. “There’s an 800-pound bear on the trail a half-mile up,” they said. “It took us an hour just to get around him. He won’t move, you can shoot all the pictures you want.”

I picked up my pace, but when I got to the spot they described, there was no bear. I could see where he had been digging, and found some fur laying around, but that was it. I’d have to sleep that night knowing he was wandering around somewhere nearby.

In the middle of the night I awoke to something trying to make off with my pack. I clapped my hands, and just as my eyes adjusted to the light, I’d see it was a deer that wanted the salt off my straps.

Because of the backcountry permit process, I could only hike another 14 miles the next day, but it was a gorgeous section, so I didn’t mind taking my time. The highlight was the approach to Stoney Indian Pass, which was loaded with jagged mountains, huge waterfalls, alpine lakes, and wildflowers.

The backside of the pass involved a little snow travel, but nothing that required an axe or crampons.

That night I slept at Waterton campground, another landmark on the CDT. In the morning I woke to what sounded like a light drizzle, but when I opened my eyes, I found it was the pitter-patter of hundreds of hungry flies scampering across the top of my tent.

My permit included one more night in the park at the Bowman Lake campground, but I got to camp early in the afternoon and felt strong, so I pushed on and hiked a total of 32 miles to reach the edge of the park at a tiny mountain town called Polebridge.

I arrived at the Northern Lights Saloon at 8:55p.m., just five minutes before the cut-off to order a pizza, and I ate while a couple of musicians played live music on the front lawn.

I spent that night at a hostel up the road. It was owned by a German man named Oliver. He showed me around, gave me a towel for the shower, and then let me get some sleep. The hostel is off-grid, relying on solar, propane, and a wood stack for power.

In the morning I talked to Oliver before heading out. He explained: “I first came here 20 years ago by chance. Twelve years ago I bought it, and I’ve lived here ever since. This is a special place. Europe has a lot of places to hike, but nothing compares to the wide open spaces of the American West.”

After Polebridge, I left to traverse the Whitefish divide. It was a long forest service road walk to the beginning of the trail, which climbed to the top of the divide and then followed the crest from peak to peak. The ups and downs and steep grade of the trail reminded me of the Appalachian Trail.

The next day I hiked down to the Grave Creek trailhead, where I stopped to make dinner just as a truck came rumbling down the dusty gravel road and then stopped in front of me. It was a border patrol agent, and he wanted to know what I was doing out there. I told him about my hike and he was incredulous.

“Now why in the hell would someone want to go and do that?! I take it you ain’t afraid of wildlife,” he said, “but you should be. Out here we’ve got black bear, GRIZZLY, wolves, mountain lion….”

I showed him my can of bear spray.

“You got any more of those?” he said.

“No.”

“Well, then you’ll probably have to replenish.”

I told him I had seen tracks, and scat, and some fur, but no big predators, but he assured me I would; that I could count on it.

He started to roll up his window and drive off, and I heard him exclaim to himself, “psh! walkin’ out here!!!”

I walked the rest of the way to Eureka, Montana, without incident the next day.

I still haven’t encountered the grizz.

—Contributing editor Jeff Kish is hiking the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail this summer. He will be making regular trip reports and gear reviews from the trail. This week he reported on the KEEN Durand boots, in which he hiked the first 138 miles of the trail. Follow the whole journey at GearJunkie.com/PNT.