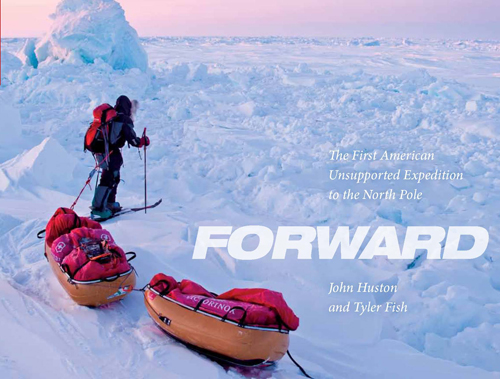

“Forward,” a new book by John Huston and Tyler Fish, tells the story of the pair’s attempt (and eventual success) in 2009 to become the first American unsupported expedition to the North Pole. Over two months, the team skied more than 500 miles, hauling huge sleds, maneuvering through endless ice rubble fields, and even swimming across stretches of open water when the frozen terrain evaporated in their path. Published by Octane Press, and available for sale beginning this week (ships December 15, 2011), GearJunkie was granted rights for an excerpt of the book’s first chapter, which was written by John Huston and Chris Niskanen. Zip your parka and cinch the hood on tight. “Forward” is a chilling read right from the start. —Stephen Regenold

Excerpt from Forward by John Huston and Tyler Fish. Reprinted with permission of authors and Octane Press. All rights reserved.

Day 47: April 17, 2009. We stand atop a frozen sea that stretches out before us. For these past forty-seven days it has been our constant companion and our home. We have skied, snowshoed, and sometimes even swum toward the North Pole, climbing over ridges and threading our way among ice boulders large and small. In our backpacks and in Kevlar sleds called pulks, we carry or haul everything we need to sustain us on our journey: food, clothes, tents, navigation gear, and satellite phones. No Americans have ever traveled under their own power to the North Pole without resupply. We hope to be the first.

In the next few days we expect to begin an all-out race to the Pole. We have 103 nautical miles left to go. A Russian helicopter is scheduled to pick us up in eight days. If we don’t meet this deadline, we fail.

It is mid April, the spring season on the Arctic Ocean. This morning at 5:00a.m., like every other morning of our trip, we rose from our down-insulated sleeping bags and quietly prepared for another day on the ice. With daylight lasting twenty-four hours, the tent was bathed in sunlight as we fixed our breakfast by thawing out a block of pemmican—a mixture of meat, fat, vegetables, and spices. A half-stick of butter topped off our fatty stew. We have come to love eating chunks of butter and deep-fried bacon, two staples of the super diet that keeps us alive. Hauling our heavy loads in this brutal cold means we need to consume calories at the phenomenal rate of at least seven hundred per hour, almost four times the norm for a person walking, say, along Lake Michigan on a November morning.

Our thermometer this morning read -34° Fahrenheit. Now, four hours later, the temperature has risen to a balmy minus-10 degrees F. We eat, sleep, and ski. Sometimes we climb over chunks of ice the size of Volkswagens. To cross short stretches of open water we put on waterproof suits called drysuits and swim through slushy seawater, towing our floatable pulks behind us.

At this moment my blood is warm and my mind awash with problems, some technical and some personal. We halt at the edge of a lead—a gap in the sea ice—which froze over maybe a day or two before. Floating on the Arctic Ocean are giant plates of ice that constantly move and grind against one another. Stretches of water called “open leads” are formed when these plates pull apart. Open leads sometimes look like small rivers or creeks with no current. Eventually, these leads will refreeze, but with a thinner layer of ice.

I am staring at the ice in this lead, wondering if it will support my weight and the one hundred pounds of gear in my pulk. The lead is dark and speckled with frost flowers an inch high. Dark ice is new ice. I hope it will hold us. The ocean below is two and a half miles deep.

I punch the ice with the tip of my ski pole. It doesn’t poke through. The rule of thumb: If the ice doesn’t give after three good jabs, it’s usually solid enough to ski across. “It looks like the same ice we skied over yesterday,” Tyler calls out over the wind. “It looks good.”

Tyler Fish is thirty-five years old, a powerful and skilled cross-country skier, and my partner on this 413-nm (nautical mile) journey to the Pole. A ruff of wolverine fur, heavily encrusted with frost, frames his bearded, weather-roughened face. His wife Sarah and infant son Ethan are waiting for him back home in Ely, Minnesota.

Tyler and I trust each other implicitly, but lately our relationship has had its tensions. We’ve known each other for nine years, since our days working together at Outward Bound, the famous outdoor leadership school. Now, we are like soldiers marching through a moonscape of ice, dependent on each other for survival. Our ability to excel as a team, assessing our progress and mulling over each predicament we face, will determine the success of our mission.

continued on next page. . .