International Adventure Girl: Bria Schurke

By STEPHEN REGENOLD

published March 20, 2008

The year was 1989, the Cold War waning but not yet dead, when Bria Schurke was ushered into the U.S.S.R., slipping in backstage via Siberia, where her father was leading a winterlong expedition through a region long locked off to the outside world.

A series of summer Siberian treks followed on which Bria would raft rivers and pick mushrooms and hunt with reindeer herders. Schurke—a girl from Ely, Minn., just 4 years old at the time—remembers the camps, firelight flickering, the Russians dancing and drinking vodka into the night.

She can see salmon swimming in the whitewater, berries gathered in baskets, the big orange Russian helicopters laboring to transport the crew far and deep into mountains at the end of the Earth.

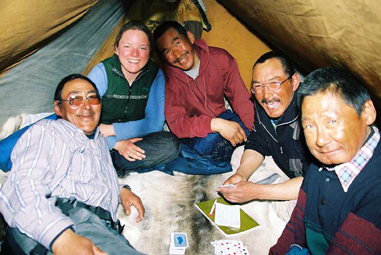

above: Schurke in Greenland, 2001

As glossy childhood memories go, Iron Curtain adventure travel is certainly rare. Disneyland it was not. But maybe not so rare for a girl who went to the North Pole in first grade, who picked through mammoth bones with a paleontologist on Russia’s Wrangel Island while still in junior high. Then there was the raw seal meat, consumed at age 15 with Inuit hunters on Greenlandic pack ice.

“It was very fatty and fishy and chewy,” she said. “I kept gnawing and gnawing to get it through my mouth.”

Adventure is not only in Schurke’s genes; she knows no other way to live. The 22-year-old senior at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn., has led a life straight from the pages of National Geographic magazine. Monthlong treks, expeditions, mountain climbs, Arctic journeys and world travel are a given in a young life that’s had few boundaries.

“I grew up being dragged along to places like Canada’s Ellesmere Island and the Kamchatka Peninsula,” she said.

Bria is the first-born child of Paul and Susan Schurke, natives of the Minneapolis area who pulled up roots in 1981 to move to Ely. They paid $1,800 for a ramshackle home built by Yugoslavian immigrants in 1880, with old jeans and calico dresses stuffed in the walls as insulation. The Schurkes lived in the 15- by 30-foot house until Bria was 8. Susan opened a clothing company and Paul built a résumé that included the expeditions to Russia and, in 1986, an unsupported dogsled trip with Will Steger and Ann Bancroft to the North Pole.

above: Schurke in Greenland, 2001

Two more Schurke children came in time: Peter, born in 1992, and Berit in 1993. Paul continued to lead trips as the kids grew up, gaining credibility as one of the world’s great polar explorers. National Geographic, the Discovery Channel, Smithsonian magazine, Dateline NBC and dozens of other media outlets documented his exploits.

In 1987, Paul and Susan opened Wintergreen Dogsled Lodge on White Iron Lake outside of Ely at the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. They kept 24 sled dogs in the back yard. In summer, Bria drank water straight from the lake, dipping a cup from a canoe.

The business brought hundreds of guests each winter, some from as far away as South Africa and India who had never seen snow. They journeyed to Ely to sled, to winter camp and to see the aurora borealis, guided by Paul, Susan and the kids.

“My nearest neighbor was 20 minutes away down a dirt road,” Bria said. “But we had the world coming through our door.”

The kaleidoscope of cultures she saw both at Wintergreen and on her trips forged a worldview not common for someone who grew up for the most part without running water or electricity. She left for college in 2004, a customized major in international public health and sustainable development her goal. She studied Russian and Swahili.

She also skied, taking the position as captain of the women’s Nordic team at St. Olaf. Athletic highlights included taking second place at two national meets and 33rd place at the American Birkebeiner in Cable, Wis., in 2006.

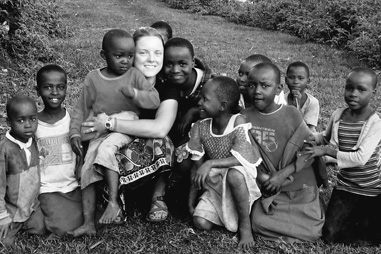

To expand her international grasp, Schurke went to New Delhi, India, last winter on a medical internship. In August, it was off to Kenya, where she lived and worked in Kibera, a sprawling slum that’s among the largest and most desolate on the continent. To describe the experience, she threw out words like “chaos” and “insanity.” “Someone was stoned and burned the first day I was there,” she said. “He was killed for stealing a loaf of bread.”

above: Schurke in Kenya, 2007

During her three-month stay in Kenya, Schurke worked in a hospital treating children for malaria. She delivered babies, four in a single morning once. “Birth is a pretty cool thing,” she said. At night, walking home, she kept her head down, watching out for “flying toilets,” bags of human waste tossed into the streets. “Kids were playing in the gutters, marinating in sewage.”

She left in December, as violence closed in on Kenya after the country held disputed elections over which thousands have been killed.

Back at Wintergreen Lodge, life was quiet, cold, pristine. She skied and guided dogsled trips—“a very different existence from Kenya,” she said.

Schurke finishes her degree this spring. She plans to take a pause from academia before applying for medical school. Her goal is to become a doctor of osteopathy, a rising health care area that emphasizes a holistic approach to treatment. Schurke said it’s the kind of medicine you can practice anywhere, from remote villages in the Russian Far East to big cities in the United States.

In the meantime, she is applying for a guiding position at the National Outdoors Leadership School, a Wyoming-based wilderness program. She is dabbling in photojournalism, including images from her time in the Third World. “The right photographs can make an impact,” she said.

Last month, before returning to Northfield, Schurke went on a final pregraduation adventure. This time the location, the Kabetogama and Sturgeon River State Forests of northern Minnesota, was not so remote. But the challenge, the 135-mile-long Arrowhead 135 Ultramarathon race, would draw from her lifetime of challenges and physical training.

As she toed the line on Monday, Feb. 4, she knew that only one person—and no women—had ever finished the race on skis. She pulled a pulk sled full of supplies and skated off on a 60-hour rolling course, no outside help allowed.

She skied from early morning until 10 p.m. the first day, collapsing into sleep at a trailside lean-to. Tuesday was even longer: She skated and pushed all day, into the night, until 3 a.m. The temperature dropped to minus-20 degrees. She was alone in the woods, under a black sky, kicking a makeshift bed in the snow on the edge of a spruce swamp.

“I was dehydrated and frozen and physically maxed,” she said. “Once I got in my bag, I was convulsing with cold.”

But she dredged up something to keep her situation from getting worse. She flicked a match. Lit the stove. Boiled water and filled a bottle, shoving the steaming plastic vessel into her down bag. Ate a Clif bar and granola, drank hot water, slept.

In the morning she got up and clicked back into her skis, just 20 miles to go. By noon she skated across the finish line, 135 miles and 53 hours from the start. “Physically, it was the most challenging thing I’ve done in my life,” she said. “It opened my eyes to what the human body is capable of doing.”

She finished the race on Wednesday, exhausted, feet frozen and wrecked, mind swimming. School began at St. Olaf on Thursday. So she packed the skis away and drove south with a hacking cough, six hours to Northfield. Classes were starting. It was her final semester. She was soon to begin the next phase, the big adventure that is to be the rest of her life.

(Stephen Regenold writes The Gear Junkie column for eleven U.S. newspapers; see www.THEGEARJUNKIE.com for video gear reviews, a daily blog, and an archive of Regenold’s work.)