Story and Photos by STEPHEN REGENOLD

The climbing route is called “Oxygen Cocktail.” It begins in a cave — a line of chalked holds leading from a dank corner where the air is tight. It juts out through an overhang of rock, a stiff section where Pi Vongsavanthong, a climber from Minneapolis, will dangle upside-down.

“You got it, man!” shouts a spotter, urging Vongsavanthong as he fights gravity on steep stone. Vongsavanthong is ascending Oxygen Cocktail without a rope. His feet search for grip. Tendons in his arms bulge. The route — an intense line on a boulder above the St. Croix River — is only 12 feet tall.

Bouldering is a derivative of rock climbing that focuses on some of nature’s smallest climbable objects. But what the sport lacks in height it makes up for in difficulty. “Bouldering is, physically, the most demanding form of climbing,” said Duane Raleigh, Editor in Chief of Rock and Ice, a climbing magazine in Carbondale, Colo.

(Click for BOULDERING PHOTO GALLERY)

While there are easy routes on boulders, climbers tend to focus on the sheer and improbable areas where limits are pushed. Routes on boulders are referred to as “problems”: Solving the physical riddle to climb a blank boulder face can be a feat of strength, balance and choreographed moves.

“Moves tend to be very gymnastic and require short bursts of energy,” said Jason Noble, district supervisor at Vertical Endeavors, which operates climbing gyms in Minnesota and Illinois. Vongsavanthong is a marketing director at Vertical Endeavors. He trains at the company’s flagship gym in St. Paul, which recently expanded its artificial bouldering area to about 2,500 square feet of indoor floor space.

Despite an emphasis on advanced-level problems the likes Oxygen Cocktail — which is a route at Interstate Park in Wisconsin — bouldering is a good way for beginners to try climbing. The skills required in rock climbing — knot-tying, belaying, anchors, commands — are not needed on the small stones. Bouldering quickly introduces the fundamental idea of climbing: simple movement on rock.

(Click for BOULDERING PHOTO GALLERY)

Raleigh added that bouldering is a “low-cost, accessible and low-risk entry point into climbing.” He said a climber can be outfitted for less than $400. Ease of access is also driving participation. Based on industry figures, Raleigh estimates there are more than 500,000 boulderers in the United States.

At Interstate park — a popular bouldering area on the Minnesota-Wisconsin boarder — a weekend day can see a couple dozen people hiking under pine trees in search of vertical “problems” to solve. I met up with Vongsavanthong and his group in mid-August. Four friends set out with their gear marching downhill to a site called Cave Boulder. “Down this trail,” said Kris Johnson, pointing into the brush.

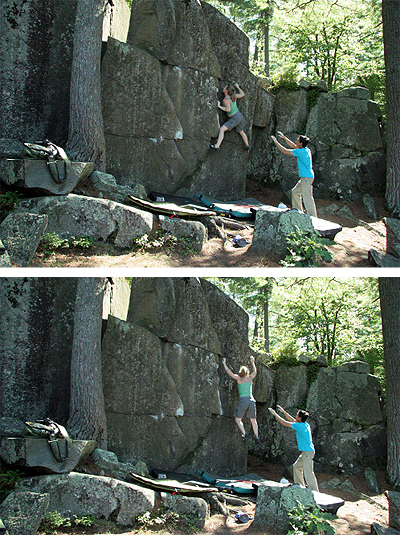

On the approach, Johnson and his wife, Lynn, toted bouldering crash pad, which look like mattresses with backpack straps. The foam pads protect boulderers in a fall. When a climber gets high on a boulder, a spotter — arms raised, head up — moves in to aid in directing a falling climber to land on the cushioned pad.

(Click for BOULDERING PHOTO GALLERY)

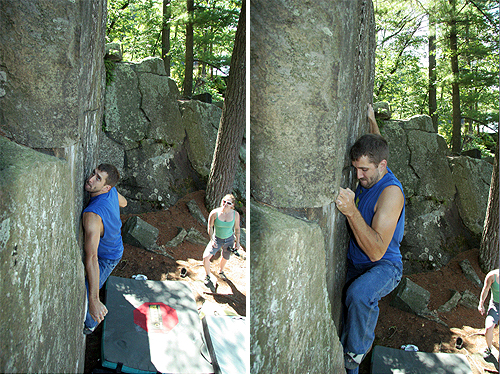

Before starting on the first climb, Johnson walked to the base of Cave Boulder and brushed off a hold with his hand. More serious, Trinh Mai took out a small brush and started scrubbing ledges and chalk-encrusted holds. “Old stuff from past climbers,” she explained.

Instead of ropes and carabiners, the crew’s equipment included climbing shoes, chalk bags, and pads. Kris Johnson brought an emery board and went to work on his hands. “Got to file away the calluses,” he said.

With the holds brushed — and his digits polished clean — Johnson eased onto the Cave Boulder’s main line. He reached and pulled, fingers crimped on thin edges. Vongsavanthong moved close to spot when Johnson got near the top. “Go Kris, you got it,” he said.

(Click for BOULDERING PHOTO GALLERY)

Trinh Mai, a lithe and fit climber, was up next. She moved to the back of the cave and pulled onto Oxygen Cocktail, her toes jammed in small holes. Mai rose off the pad in a reverse push-up motion, a hand stretching for a hold.

After a move, her foot slipped. Her hand dropped from a hold, and Mai crashed onto her back from four feet up, safe on the pad. Johnson pointed to a hold Mai missed. “Try that pull,” he suggested.

(Click for BOULDERING PHOTO GALLERY)

Mai scooted to the back of the cave again. She dipped her hand in a chalk bag and breathed, looking up. Mai moved onto the face. Her body swung upside-down with shoes stuck, improbably, like ant feet on a ceiling.

The top was eight feet away. Mai climbed on sharp edges, onto a slippery face. A few feet to go. Looking up. Reaching. Defying gravity for a moment on a small stone.

—Stephen Regenold writes about outdoors gear at www.gearjunkie.com.