We slept in an RV parked in my friend’s yard. He keeps it there, stowed permanently, for people needing to crash when coming through town. It was Labor Day weekend, sunny and 70 degrees, a perfect day in a port city known for fickle weather on the edge of the world’s largest lake.

I was up to visit for a few days with my kids. A long weekend would include Lake Superior swimming and exploring the city’s famous trails. We’d hike, rock climb, mountain bike, and maybe find time to inflate the packrafts stowed in the back of my van — just some of the many things to do in Duluth.

As urban adventure goes, Duluth is hard to compare. Within city limits, you have ski areas, creeks, crags, beaches, and trails. Ice climbers scale frozen quarry walls. Backpackers trek the Superior Hiking trail. Mountain bikers come for a paradise of singletrack, 100+ miles and more added every year.

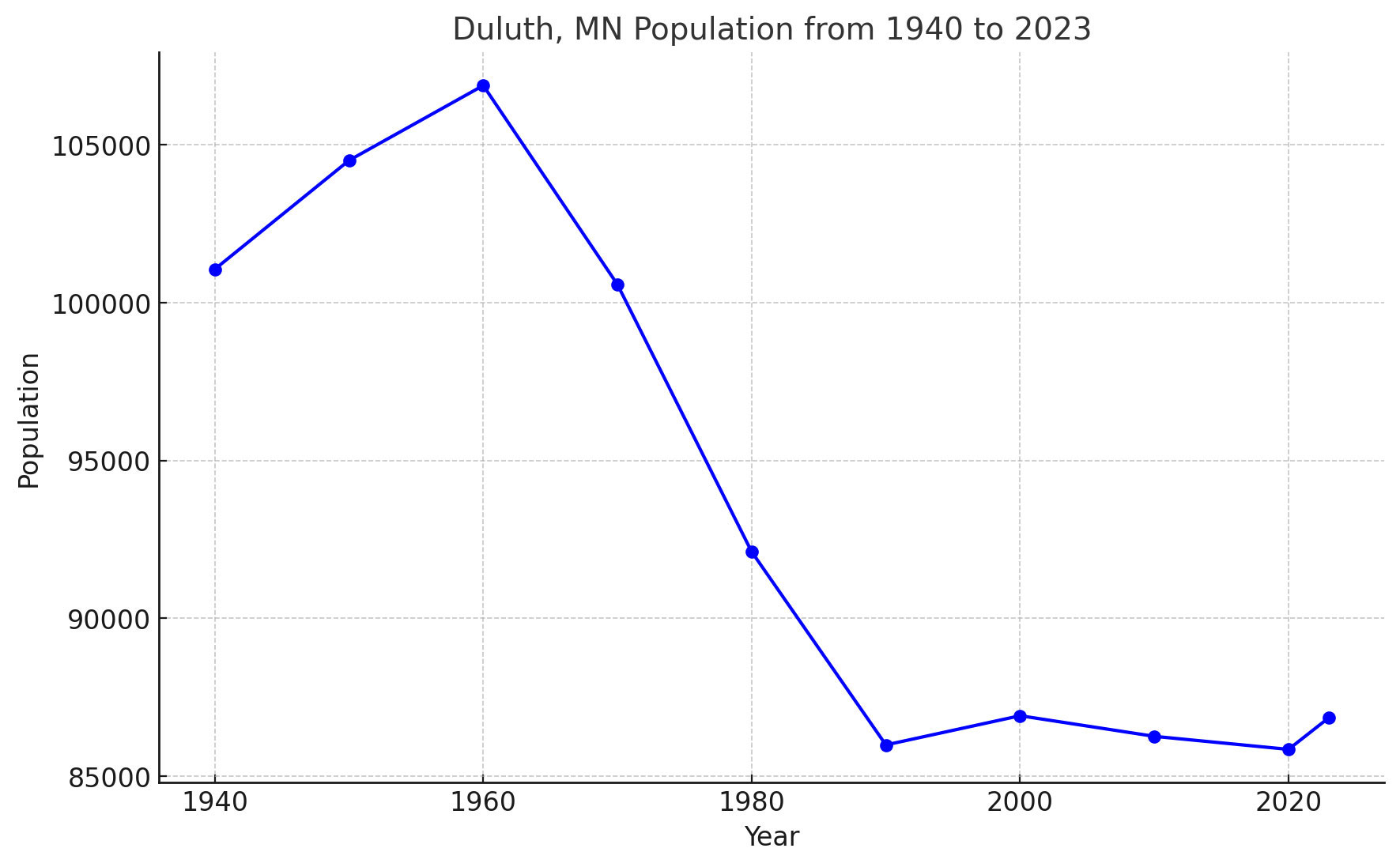

Since 2010, Duluth has invested tens of millions of dollars in building itself into an adventure hub and a good place to live. Some elements paid off, including hundreds of miles of trails and tourism numbers that are on the rise. But the town’s population remains flat. In 2024, Duluth is feeling both the prosperity and pains of its long-term tourism-centered strategy.

Boom Town Past

Images of the outdoors drive Duluth’s brand. Brochures reveal mountain bikers and crisp fall hikes. Tourism materials tout pristine shores and a place that is “part rugged, part refined.”

In the town of 86,697, bridges and ore docks dominate the view. Gentrification has come to a select small area primarily where the tourists go. Much of Duluth is rugged to the core.

Long an industry town, lumber and iron were the lifeblood here. Trainyards and factories facilitated raw materials coming from forests and mines.

An era of extraction engulfed the port. Smoke pumped and factories churned. Smelting, milling, slag piles, and waste.

It was boom times, resources flowing from an endless North Woods. Aggregate and ore piled high, loaded to docks, and dumped onto freighters a thousand feet long.

You’d look east and squint, 2,300 miles on the Saint Lawrence Seaway to the Atlantic coast beyond. Duluth is the planet’s farthest-inland freshwater port, and 80 years ago it shipped “iron ore to win the war,” as the old saying goes. Allied Forces built tanks and airplanes from metal originating in Minnesota mines.

A post-war high. A Baby Boom swell. Then, it all began to fade.

Decades of Decline

Recession came after the boom, and by the 1970s once-strong industries were going bust. U.S. Steel suffered a slow death, thousands of workers dismissed in its decline. Businesses closed. Jobs evaporated. People moved away.

A billboard appeared on the highway in 1982 to illustrate the collective defeat: “Will the last one leaving Duluth please turn out the light?”

A quiet decade came next. Those were my childhood years. Duluth had a scent to it, I remember from trips. Smoke and something like rubber burning, tinged with the sulfur stench from a paper mill.

Buildings slumped. Siding molted off house after house, faded neighborhoods devoid of people on dead winter days.

You looked up to the hills and saw beauty and trees. Lake Superior was an infinity of blue.

I grew up in the Twin Cities, 2 hours south. When the family went to Duluth, we’d watch ships in Canal Park and stop at a free museum managed by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Mostly, we drove right past. The North Shore, the pristine arrowhead of the state, beckoned beyond on Highway 61. Duluth was a gateway where you stopped for coffee and fuel. You hit the gas and left as quickly as you came.

It hardly resonated as a place to recreate. A Rust Belt vibe was at odds with the reason to head north — to escape from the city and into the woods.

A Town in Transition

My relationship with the place goes back as far as I can think. My memories are foggy, literally, from when I was a kid. Skiing with my dad, we took a chairlift ride up Spirit Mountain in a rare winter rain. A whiteout haze rose from the lake. I could hardly see the tips of my skis.

Soaking wet, I slid on an ice sheet in a void. Locals bombed past in plastic bags, the ad hoc rainwear buzzing with wind.

As I got older, my friends went to college at the University of Minnesota Duluth. My brother met a girl and moved there in 2006.

In my 20s, I was sent to Duluth as a young journalist by The New York Times. It’s an underdog town that looks good in pictures. It had a sense of intrigue, and I wrote about ice climbers and surfers who sought waves in winter storms.

Today, we have family and friends around town, many transplants from Minneapolis pulled north by the allure of the Great Lakes.

But they were the rare ones. The locals had been moving away, and the population sank and sank, hitting 100-year lows.

Duluth’s light was dim in the ’90s and early 2000s. But maybe the outdoors could bring it back.

Time to head into the woods and look around.

A New Vision

Duluth’s transformation began around 2008. A new mayor, Don Ness, proposed a vision to combat unending economic woes. Ness and a small group saw the city’s natural assets — its rugged terrain, forests, and access to Lake Superior — as a different way ahead.

What happened next was a whirlwind few years, a renaissance in which hikers, climbers, skiers, and mountain bikers drove new energy for the town. The vision was clear: rebrand Duluth as an outdoor adventure hub. But first, build the infrastructure needed to improve the experience and make it accessible to all.

By 2010, a strategy was formalized to put outdoor recreation at the heart of the city’s economic plan. A bike project kicked it off. The Cyclists of Gitchee Gumee Shores (COGGS) pitched the Duluth Traverse, a 100-mile trail. The project, soon backed by a $250,000 grant, set out to create America’s longest urban mountain biking trail.

A city tax on lodging and food was reestablished in 2014. The funds quickly built into millions of dollars of annual revenue, much of which went directly into projects focused on the outdoors.

Over the next few years, trails were carved through the city, building momentum for a new identity. Breweries and restaurants opened. Canal Park, the main tourist district, grew with shops and hotels into the most “refined” part of the town.

I was in and out of Duluth during this rise. I saw the change in new trails, new terrain, and a bit of shine on the Rust Belt grid.

At GearJunkie, we were biased toward the place. Duluth got a spot in our project, “The Great Urban Outdoors,” with a video and articles highlighting a new vibe.

Accolades started to appear. The International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) gave the city a rare Gold-Level ranking.

People were no longer driving past Duluth to the North Shore. It was a destination now, and you came with climbing ropes and mountain bikes ready to go.

Center Stage, Briefly

Could Duluth be the next Bend, Ore., or maybe Boulder, Colo.? These midsize cities were in the national spotlight, and people were vacationing or even moving to manifest new lives where urban amenities and outdoor recreation coexist.

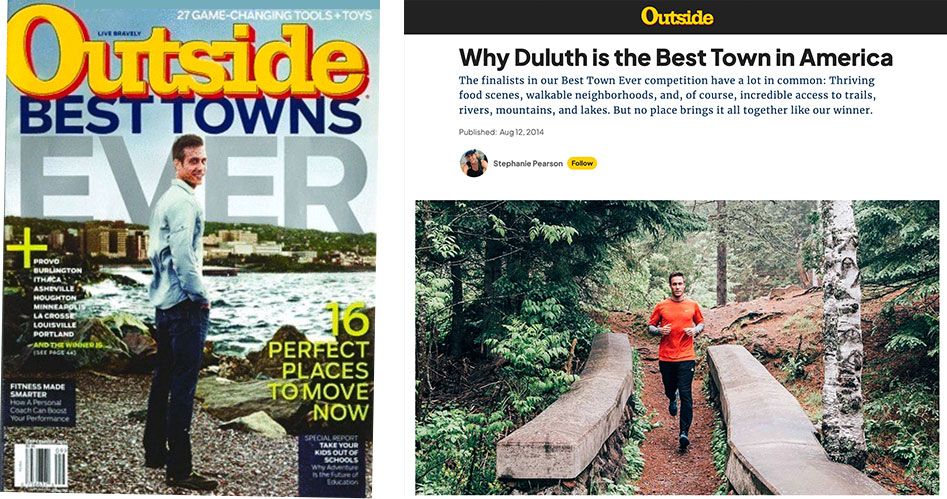

In 2014, validation came in the form of a glossy magazine cover. Outside crowned Duluth as the “Best Town in America,” citing Mayor Ness and the efforts of local groups.

Writer Stephanie Pearson, a Duluth native, divulged on parks, trails, and trout streams. Seeing the city in the magazine ahead of more-known adventure towns was a civic point of pride. Locals still talk about it to this day.

Tourism campaigns and grants fortified the buzz, bringing new people to town. The goal was tourism, with a second-order strategy of more people putting down permanent roots.

Life in Duluth: A Good Place to Live

My brother lives off Anderson Road. Kids’ toys and a chicken coop take up the backyard. Scrappy woods block the neighbors’ houses behind.

He grew up in the Minneapolis suburbs and put down Duluth roots after college. Wife, kids, a dog, and a garage full of gear, they live in a sprawling part of the city that could be Anytown, USA. But behind the car washes and fast food joints the trails unfurl to all compass points.

We roll from his garage on mountain bikes and pick up the Traverse trail. Five minutes from a Starbucks, we are off the pavement and into the woods, pedaling a flowy stretch of singletrack with Lake Superior below.

Plank bridges span streams. Soon, a stretch of bedrock appears, the trail routed onto the exposed “natural pavement” of the Canadian Shield.

In Duluth, just under 20% of municipal land is designated as green space, and that ratio is on the rise. Over the past year, 500 land parcels were procured by the city via purchase and tax forfeit to convert private deeds to public space.

Beyond land, the St. Louis River National Water Trail is nearing completion this year. It traces the nation’s largest freshwater estuary where river water fades into endless Lake Superior blue.

It’s a good life here. But growth remains elusive even a decade later from the Outside award. Mayor Ness, bullish for expansion, set a goal for 90,000 residents by 2020, after his term.

Infrastructure is built to support about 110,000 people, near where the population peaked in 1960. Yet current numbers are far below that, and the town shows it on empty streets and building after building in need of repair.

Long winters don’t help. You need to love snow to live up here; the average temperature in January is a frosty 8 degrees.

Like many places, affordable housing is scant. There is a general real estate crunch, more demand than supply across the town.

A slight upswing of around 1,000 residents have moved here in recent years. The new city leader, Mayor Roger Reinert, is revisiting the 90,000 goal. The post again moved ahead to 2030 this time.

Change in the Air

Despite a population plateau, a surge in tourism is tangible from restaurants to rock climbing crags. Visitors now add nearly $800 million annually to the area’s economy.

Millions more people come to the northern city than a decade back. In 2022, one of the most recent studies, an estimated 6.7 million visitors arrived. It’s a notable increase from 2014 when 3.5 million folks made the trip.

The city estimates further growth. Numbers are nudging closer to an elusive $1 billion in annual economic impact from people coming to ride trails, ski, dine, sleep, and head into Canal Park in search of souvenirs and smoked fish.

Business travel is a part of it, too, with dozens of trade shows and conventions per year. This includes the Great Lakes Outdoor Summit this month, October 24-26. (GearJunkie will be there with a booth and a prize wheel where you spin for swag!)

A final gauge with the outdoors push can be filtered via a look at local life. The daily quality of existence in Duluth has improved over 10 years. It’s not just trails and ice-climbing crags.

On a sunny evening last month, we grabbed birria tacos at a new place off Superior Street. Live music pumped from a beer garden nearby. There was an energy on a stretch of street that was formerly rundown and sad.

An old friend texted me after dinner. He was staying in Duluth for a week and saw my van while biking around. “I think I need to move up here,” he wrote.

He was working on a construction project and exploring Duluth by bike every night. He gushed about the trails, the big lake, and the town that, after years on the slide, was fully coming back to life.

Great Lakes Outdoor Summit 2024

Want to experience a full blast of the Duluth scene? The second annual Great Lakes Outdoor Summit, October 24-26, brings together outdoor enthusiasts and professionals for training, networking, and expert-led sessions.

Keynote speaker Connor Ryan, an Indigenous skier and filmmaker, will explore traditional ecological knowledge and its connection to outdoor pursuits. The event offers 12 sessions, 40+ exhibitors, including a booth from GearJunkie, and guided outdoor activities. A live recording of The Dirtbag Diaries podcast with host Fitz Cahall is scheduled for the first night. Registration is open now.