[leadin]On a cold morning in September, the clouds rolled over Oregon’s Cascades. Dark grey and dimpled, they looked like overstuffed pillows snagged on the mountain summits.[/leadin]

It’s on days like this that Jon Tullis, spokesman of Timberline Lodge ski resort at Mt. Hood, watches the Palmer Snowfield at 8,500 feet — often with worried thoughts.

On that day, only a thin layer of snowflakes fleeced the Palmer, a dusty white patch on a brown mountainside. September doesn’t usually bring much snow, but after a mild winter last year and a hot summer, this month has so far kept up with the kind of disappointment that’s been commonplace all year long. Timberline Lodge sits in the heart of the Central Cascades, which has been going through its most severe drought in decades.

“We’re seeing areas of the mountain that we don’t normally see,” Tullis says. Palmer Snowfield is a layer cake formed by centuries of snowfall, on top of a permafrost layer of geriatric ice in a depression on Mt. Hood’s southern face. Geologists have dated the Palmer’s existence back to 1350, though it has probably been there for much longer. This year, a warm winter followed by an exceptionally hot summer has caused the Palmer to retreat dramatically — even exposing the green permafrost. At its best, it’s a 100-acre expanse of snow. Now, its mass doesn’t reach the chairlift.

Like the first domino in a series to fall, skiing is one of the immediate, and highly visible, casualties of climate change, which is making shorter seasons with less snowfall more frequent. By the end of the century, snow depths in the West could decline by 25 to 100 percent, according to a report by the National Resources Defense Council and Protect Our Winters, a nonprofit that mobilizes the winter sports community to fight climate change. Inevitably, ski areas at lower elevations, and even those in more favorable snow zones like the Cascades, face warmer and more uncertain and erratic futures that could look a lot more like 2015.

The cascade of consequences is long, from shifts in local economies to the depletion of local watersheds. That’s particularly true on Palmer. Unlike most ski resorts in the West, Timberline often stays open through the summer, drawing international skiers thanks to Palmer’s dependable snow surface that holds up even on the warmest summer days. But with the snowfield’s retreat, that’s changing. Timberline’s public operations shut down August 3 this year, the earliest since 1979 when the first chairlift to access the area was installed. Normally, people ski there through Labor Day.

As the summer skiing window gets shorter, athletes that depend on year-round turns will have fewer areas to train domestically. Ben Babbitt, 31, is the head coach of Alpine men’s ski racing at Ski Club Vail. His group tries to get in between 45 and 60 training days during the off-season — mid-April through mid-November. For several years, Timberline Lodge — the Palmer Snowfield — and Mt. Bachelor, also in the Cascades, were their best, and most affordable, options.

“It’s really critical that we have places like Timberline and Mt. Bachelor that allow us to travel cheaply and get those days on snow that we need,” he says.

This summer, however, Babbitt had to cancel summer ski camps at Timberline. Instead, Vail Ski Club ventured elsewhere, to Argentina, to New Zealand and to an indoor skiing facility in Lithuania. Those increased travel expenses fell on the skiers and their families. “The kids definitely know that what they are seeing is the start of climate change,” Babbitt says.

A Concern Beyond Skiing

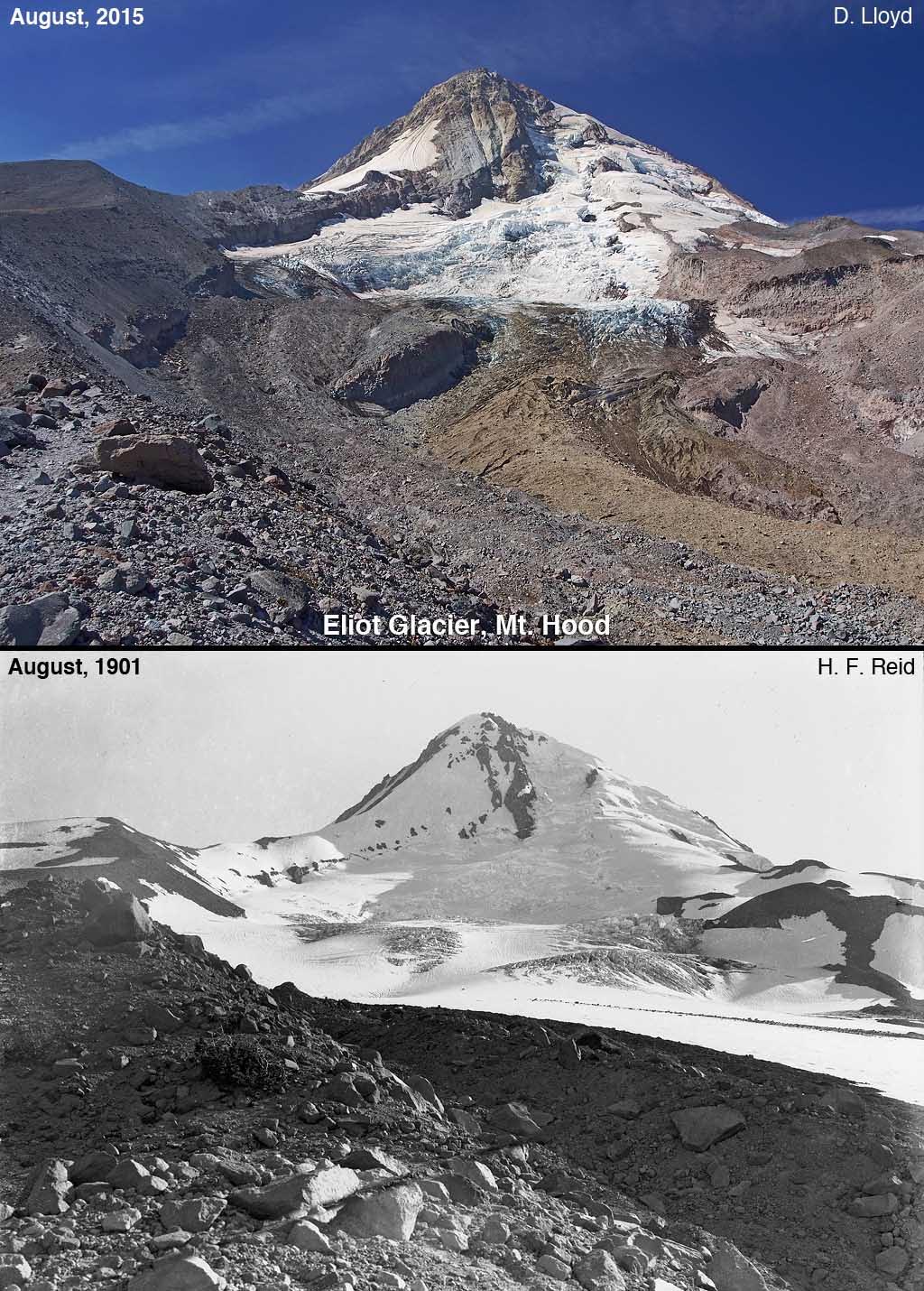

Oregon has more mountain ice than most (it’s second only to Alaska), but experts say the region’s disappearing summer skiing and shrinking snowpack are leading indicators that major climate shifts are happening. “It’s not just about skiing, but it is this canary in the coal mine — it’s really, really visible,” Anne Nolin, professor of geography and head of the mountain hydro-climatology research group at Oregon State University, says. “When things go from bright white, glittering snowpack to brown dirt and flaming forests, everyone sees it.”

With the smaller snowpack, Nolin and a team of OSU researchers took streamflow measurements this summer that were the lowest they’ve ever seen. That has a ripple effect beyond the ski area. When less meltwater flows into the streams, economies that depend on summer recreation suffer, too. This season, rafting companies experienced some of the fewest viable days for kayaking and rafting on the nearby Deschutes River. “Our society tends to ignore the fact that rural communities depend on what others might consider an elitist sport,” Nolin says. “I’m concerned about the loss of income to rural communities that depend on summer and winter recreation — everyone hurt financially this year.”

All things considered, Timberline Lodge is in a fortuitous place high in the Cascade Range. The area gets 450 inches of snowfall a year on average. Tullis doesn’t hesitate to proclaim that Timberline Lodge has the longest season in North America — for several seasons, that has been true. Even with the shortened season this year provides, the ski area has a buffer. That gives Tullis and his colleagues a chance to respond — one they intend to take advantage of.

This fall, Timberline is mapping the Palmer Snowfield using LIDAR —infrared sensing that measures distance by reflected light. That will help them make snow-farming — moving snow from other areas of the mountain and stockpiling it on the Palmer — more effective. With insight into the snowfield’s natural topography, Timberline’s management will know which areas of the Palmer will sustain the most snow to preserve as much of the Palmer as possible.

–This story originally appeared at High Country News, HCN.org.