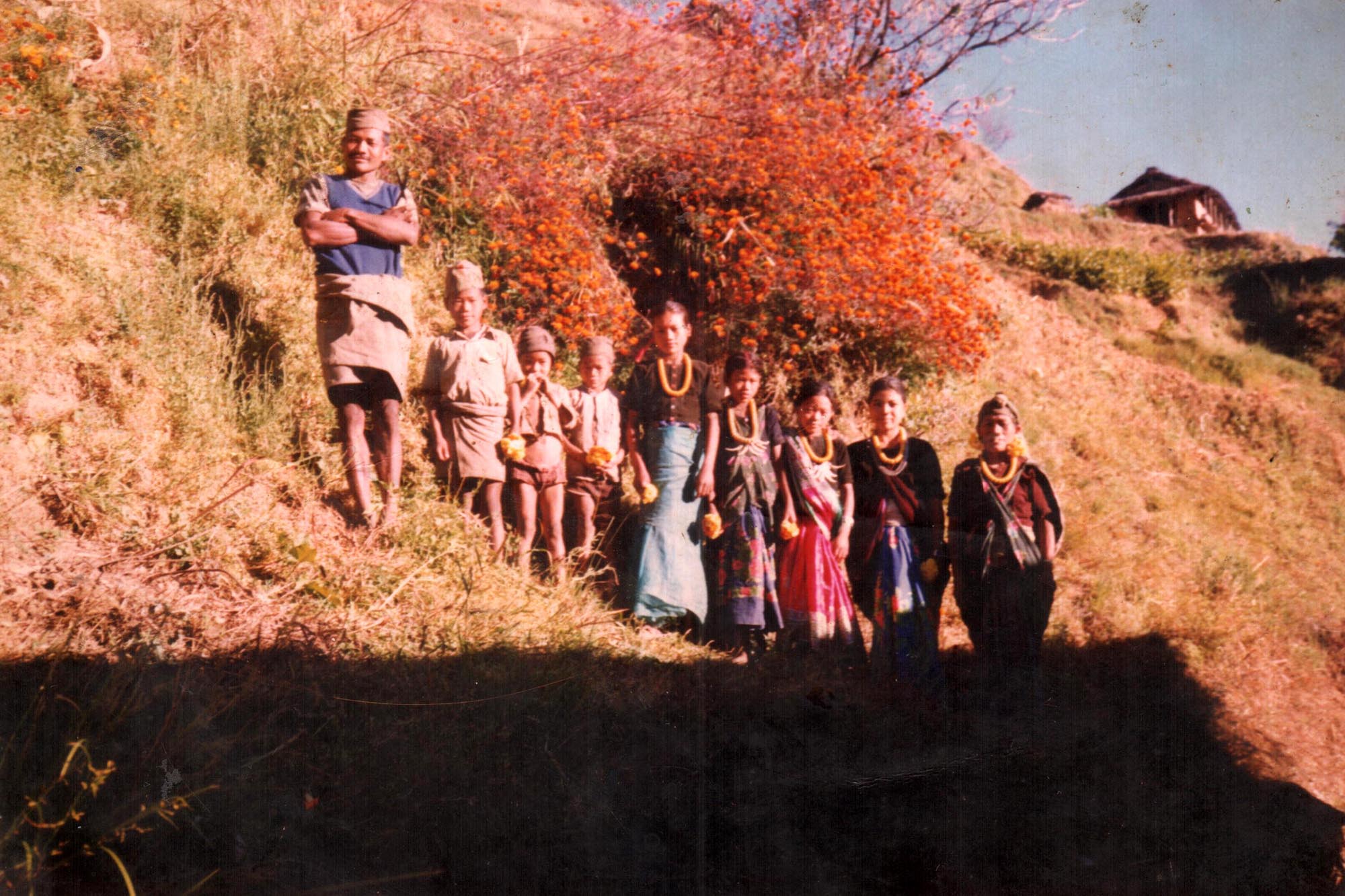

Even before the explosion from an IED changed everything, Hari Budha Magar had lived an extraordinary life. The 46-year-old grew up in a family of nomadic cattle farmers in the foothills of the Nepalese Himalayas, where the colossal mountains Dhaulagiri and Sisne were often visible over the horizon.

He was fascinated by black-and-white photographs of the historic first ascent of Mount Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. But it would be many years before his dream of reaching that summit could be realized.

As a child, he managed to avoid the violence of a civil war gripping Nepal. At 19, Magar joined the Gurkhas, a renowned special forces unit within the British military. He served in the Royal Gurkha Rifles for 15 years, traveling to many of the world’s most dangerous war zones.

Then, in 2010, Magar stepped on an improvised explosive device (IED) while leading a unit in Afghanistan. He barely survived but lost both his legs above the knee.

The next couple of years were hard for him. He became an alcoholic and repeatedly tried to take his own life. When Magar finally found purpose again, it was to prove to himself — and anyone like him — that a life-changing disability wouldn’t stop him from chasing the childhood dreams he’d left behind. The mountains were calling, and it was time to answer.

The Road to Recovery

Gurkhas have long been regarded as some of the world’s toughest soldiers, and for good reason. This elite military unit began in the early 1800s, when the British military began recruiting Nepalese fighters after a short-lived war in the region. For 200 years, the Gurkhas proved themselves fearless and capable.

Their motto? “Better to die than to be a coward.”

When Magar arrived in Afghanistan in 2010, he was a corporal and second-in-command of a 14-man team. Just 2 weeks after arriving, he was escorting a group of engineers planning to fix a local well. That’s when he stepped on the IED and nearly died from the sudden explosion: “It was very shocking. I was a big brother figure to my unit. You don’t want to leave your boys there.”

Magar’s time as an active-duty soldier was over. But the long, brutal battle to recover his self-worth was just beginning.

“For the first 2 years, I didn’t know what to do. My life was completely gone. I didn’t know whether my wife was going to stick with me for the rest of my life,” Magar told GearJunkie. “If I’m living this way, I’m definitely gonna die soon. And that’s the end of my story. I had a two-and-a-half-year-old son.”

Even Magar’s many years as a Gurkha didn’t fully prepare him for his new reality. It took him a year to learn how to walk with prosthetic legs. Among Nepalis, disability is often viewed as a karmic punishment for sins committed in a past life. So Magar, who lives in London, was often judged when visiting Nepal, and felt ashamed to be seen in public with his prosthetics.

But after 2 years of struggle, Magar changed his mindset about the future. “One day I finally decided I was going to live my life and live for my family — and that changed everything,” he said.

Finding Purpose in the Outdoors

Magar didn’t start his new journey with Everest. First, he began exploring other outdoor sports, often with the help of nonprofits that provide specialized equipment for people with disabilities.

His first experiment was skydiving. As Magar stood in an airplane soaring at 15,000 feet, looking down at the clouds below, he felt scared, he said.

“So ‘I’m a Gurkha,’ I thought. I can’t be a coward. I can’t let down my unit. So I closed my eyes and jumped,” Magar said of the tandem jump. “When we landed safely on the ground, I realized I can still do something — even without legs.”

After that, Magar tried skiing using an adaptive chair. He discovered he could go even faster than when he skied before the injury. He quickly found that he loved kayaking as well. Eventually, he began hiking and climbing with his prosthetics.

“I’m very privileged to have some nonprofits help me,” he said. “I wasted nearly 2 years because I didn’t know what I was able to do. Maybe we don’t have legs or arms or eyes or can’t hear — whatever the disability is, I think we can do something. Nobody is perfect in this world.”

When Magar finally began pursuing the mountains he’d seen as a child, walking barefoot through the Himalayas, he found a new mission. He wanted to achieve a big goal, and pioneer a trail that other disabled people could follow: “To make more awareness of disability around the world, ‘What should I do?’ Maybe climb the biggest mountains around the world.”

The Seven Summits

Climbing the highest mountain on every continent has long been considered one of the greatest achievements in mountaineering. There’s no official number of how many people have pulled off this dangerous and expensive goal, but it’s likely only a few hundred.

Magar’s Seven Summits journey began with scaling Europe’s Mont Blanc (15,777 feet) in 2019. Usually, Russia’s Mount Elbrus would be considered the highest peak in Europe. Mont Blanc was substituted in this case, as Magar didn’t decide to complete the Seven Summits until after climbing Everest, when Elbrus became inaccessible due to Russia’s war against Ukraine. In 2020, Magar conquered Africa’s Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,341 feet).

In May 2023, he went to Everest (29,031 feet). It wasn’t an easy climb. In technical sections, Magar relies on specialized prosthetics with crampon-like attachments, literally crawling his way up the mountain despite torturous pain throughout his body, from his shoulders to his “stumps.”

“When you’re moving toward the summit, we call it ‘one step at a time’,” he said. “For me, it was one inch at a time.”

He ran out of oxygen near Everest’s summit, so his climbing partner Mingma Sherpa sacrificed his own oxygen to help Magar. Luckily, another Sherpa soon arrived with extra oxygen: “We nearly died,” Magar said.

Even so, Magar became the first double above-knee amputee to reach the world’s highest peak, earning a Guinness World Record and the Pride of Britain Award.

Since then, he has continued his Seven Summits quest, summiting North America’s Denali (20,322 feet), South America’s Aconcagua (22,838 feet), and the Carstensz Pyramid (16,024 feet). Located in Indonesia, the mountain is considered the highest peak of Oceania, and arguably the most technical of the Seven Summits.

Magar reached the summit of Antarctica’s Mount Vinson (16,050 feet) on Jan. 6, 2026, becoming the first double above-knee amputee to pull off a goal that’s enormously difficult for anyone, regardless of their physical ability.

Teamwork — And the Future

When talking about the effort it took to conquer these mountains, Magar is quick to point out that he had plenty of help. He used multiple prosthetics to handle the different challenges of climbing these mountains. Often, those were carried by his teammates. Magar helped develop some of his gear, including specially designed crampons and heated sockets around his stumps.

He also had many sponsors to cover the exorbitant costs involved with completing the Seven Summits. Those sponsors range from technology and nutrition companies to veteran-focused nonprofits, professional mountain guides, and Nepalese organizations.

“To do something in life, it’s all about teamwork,” Magar said. “There’s also adaptation in accepting that help.”

Magar now serves as an ambassador for several of the charities that helped him on his journey. These include Blesma, a British charity for veterans who have lost limbs, as well as Team Forces, Pilgrim Bandits, On Course Foundation, and The Gurkha Welfare Trust. He’s working on raising funds to get prosthetic legs and wheelchairs for other disabled people, sometimes paying for them out of his own pocket.

“In the long term, I want to empower people so they can live a better life,” he said.

Part of that journey is helping others learn the lesson that came so dearly to Magar: losing a part of your body doesn’t have to change who you are.

“I’m the same guy, with the same heart and mind. I still want to dance in the party,” he said. “I’m the same guy — I just don’t have legs.”