After a lifetime of what most would label “risky” outdoor endeavors, it caught up to me as I rounded the corner into midlife. The next few years involved 12 surgeries, a divorce and child custody battle, and a near-total financial catastrophe. All from the crossing of Risk and Consequence.

I believe our society and culture reward taking risks, and I applaud that. It’s easy to see in sports and apparent in business. But these stories are curated, and we rarely see the negative totality of assuming risks that don’t produce rewards. These consequences to risk are inescapable, no matter how much we bury them behind a stonewall of success stories.

This blog was initially written selfishly as a therapy to guide me through my life’s most challenging and darkest period. Fair warning, this is a deeply personal story with some sad bits. But, there is a message that I feel applies to much of the outdoor audience. And there is a resolution. My only hope is that it helps at least one person in their time of need.

Risk and Consequence: The Relationship

Alex Honnold, the famous rock climbing free soloist (El Cap without a rope!), speaks eloquently about distinguishing risk and consequence. In his words, the risk is the probability that something terrible may happen, and the consequence is the result of that horrible thing happening.

He can remain calm while executing his death-defying climbs because he can keep risk and consequence separate and in perspective. The risk of him falling off a climb that is well below his limits is low, but the consequence is high (death). He has faith in his ability to climb the relatively easy route. He understands, as we do while driving 70 mph in traffic, that the risk of something going awry is low. Honnold is keenly aware that the consequence of an error is extremely grim but keeps the perspective clear just as we do driving on the freeway.

How can we drive at speeds that could kill us while remaining worry-free? Because driving on the highway at appropriate speeds is well within our capabilities, so low on the ability scale that we can sing along to a song or carry on a conversation. We know the potential consequence and see it in the news, but we bank on the relatively low risk of driving.

Many people have expressed that what Honnold does is extremely risky and irresponsible. But the dangers and consequences compared to highway driving can be viewed as similar. Are we all guilty of “risky” and “irresponsible” behavior when barrelling down the fast lane at 70+ mph, sharing jokes with passengers? Remember that Honnold is climbing a route that, to him, is at the same relative skill level as driving on a freeway is to us.

It is difficult for many to keep risk separated from consequence when the latter is so visible and stark. The mesmerizing draw of consequences is why people may be scared of heights. The odds of the high-rise rooftop balcony collapsing are minuscule to zero, but fear paralyzes some. Maybe some transfer this inability to avoid consequence fixation into their judgments of others; perhaps we do that to ourselves.

Suppose the odds of something going wrong, based on ability level (Honnold soloing routes well below his limits) or circumstance (the rooftop balcony collapsing), are low. In that case, the risk is low, regardless of the consequence, even if the latter is a gruesome death.

These obvious consequences can attract action sports enthusiasts, but any “daredevil” moniker is unfitting if the actual risk is low. Low risk is low risk, no matter the consequence.

The Gradual Decline vs. ‘Falling Off the Cliff’

While climbing, a partner postulated that I was making bad choices at this juncture in my life by continuing my ways of recreating. Later, the same climber engulfed a plate of fried everything and washed it down with multiple alcoholic drinks. Fun times for sure, but it made me think; certain long-term lifestyle behaviors, like diet and heavy drinking, are proven to cause increased mortality.

Smokers pay higher life insurance rates based on similar knowledge, and it’s difficult to argue the logic. People who engage in smoking, bad diets, inadequate sleep, high stress, and other detrimental lifestyle habits knowingly and willingly accept the higher risk of ugly consequences. Heart disease, cancers, and other disorders gradually, over an extended period, lead to an untimely death.

Then there are the “adrenaline junkies” like Honnold or a host of other individuals I routinely hang with. High consequences sometimes crush those that fall victim to whatever level of risk they accept, and it’s sudden. Everything is really fun until it’s instantly not fun. No gradual decline, no middle ground, suddenly you “fall off the cliff.”

Imagine a line graph. The line is life; the area under the curve is how much living is in that life. For those engaging in bad lifestyle habits but not partaking in “risky” adventures, the line gradually slopes downward until death.

Now imagine the same graph for the healthy “adrenaline junkie.” The line travels horizontally until it instantly drops, producing a rectangle. The “safe” gradual decline versus the “unsafe” instant drop, but both lines end in the same place. Maybe the first line is longer, but is that what matters? The squared-off line has more area under the curve at any point along the horizontal axis as long it isn’t at zero.

Do you want the long line, or do you want more area under the curve?

My Personal Experience With Risk and Consequence

Thoughts like these rambled in my mind frequently over the last decade. I ran into a cow on an adventure bike in Baja in fourth gear almost 10 years ago.

Seriously. It stood in the deadly mixture of dust and low-angle, in-my-face sunlight. It isn’t uncommon for riders to get killed in Baja from hitting animals.

A year later, although I summited, I took extreme risks climbing the North Ridge of Mount Baker with an injured ankle. I nearly slipped off a steep slope covered in hard ice because I couldn’t load my ankle enough to get all my crampon points in.

Then in 2018, I climbed Bridal Veil Falls (an ice climb) in Valdez, Alaska, narrowly avoiding a frozen demise due to rope management mishaps. The trickle of events that led to that near disaster is mind-boggling. If the momentum had continued, my partner would have been dead at the bottom, and I would have frozen to death at the top.

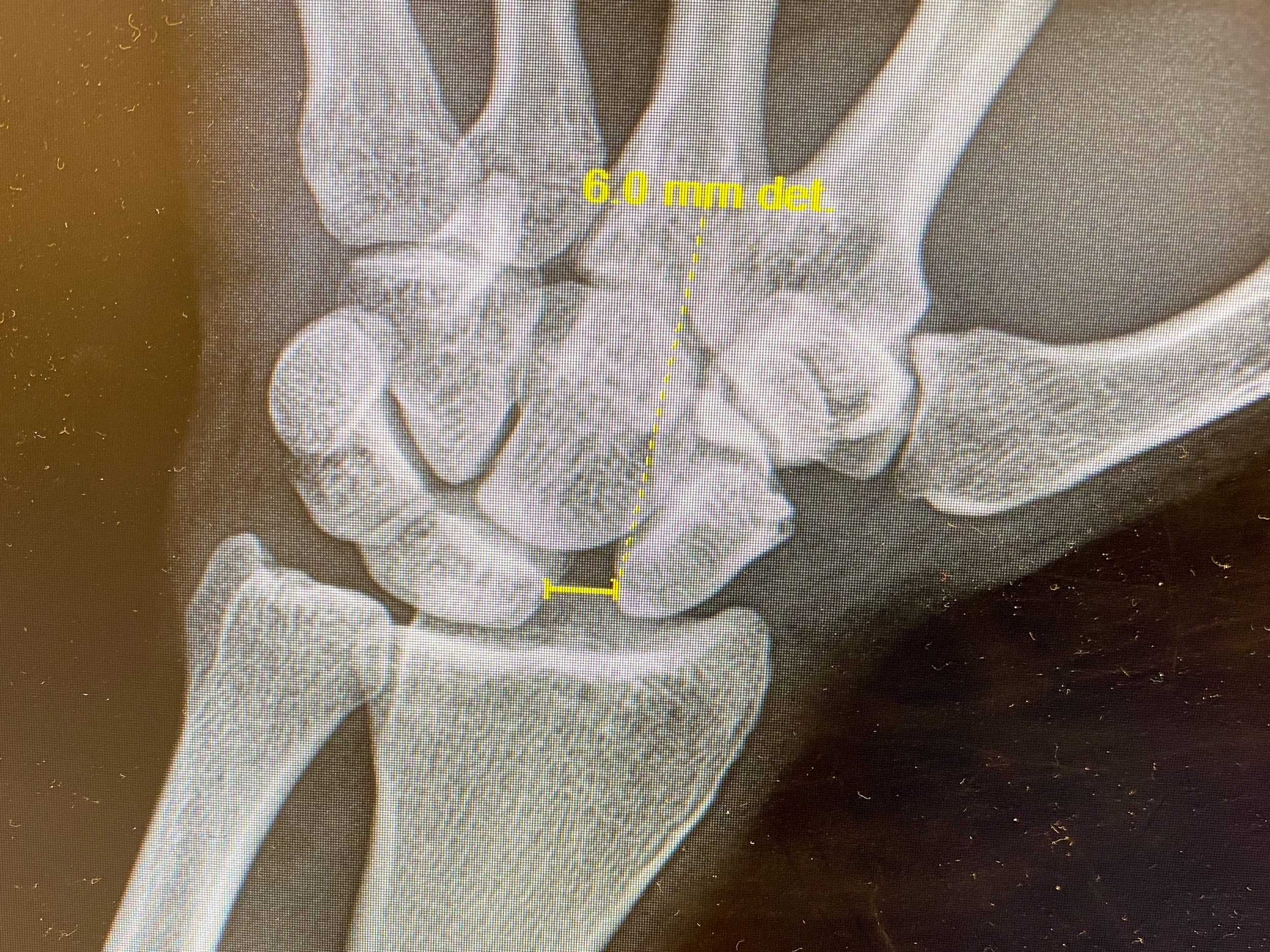

A few months later, I crashed while dirt biking, resulting in 11 knee procedures plus two staph infections and a wrist reconstruction. I was put on suicide watch during one of the hospital stays, being the statistically significant “hospital suicide risk.”

The pain was extreme at times, the worst I’ve ever felt. And I was unsure if I could ever hike, cycle, climb, or test gear and how I would support my family.

I had visions of myself sitting inside, hearing my daughter laugh and play outside, jobless and unable to participate. Nightmares that I was a dog at the end of its days, scurrying from a mountain town in search of somewhere to die, woke me frequently. All this was crushing, and the suicide watch was befitting.

But, these aren’t the sum of the consequences of the risk of riding a dirt bike that day.

The Real Consequences

The dirt biking accident caused tremendous physical trauma. But these were pale against the consequences to my family and mental health. While learning to walk again, my wife of 18 years handed me divorce papers. Although my “risky” behavior was not the only cause, it significantly influenced her decision to dissolve our family of three.

The divorce papers outlined that I would only have 3 hours of supervised visitation per week with my then 6-year-old daughter. My wife indicated that my “reckless” behavior, which included climbing, dirt biking, and bicycle racing, was unsafe for our daughter.

Our bustling house suddenly became silent as my family moved out, leaving no traces of a little girl having ever lived there. The shock of it all, combined with the struggles and uncertainty of my physical abilities, was too much.

My mental state imploded. I’ll spare you most of the dark details, but the result was three squad cars descending on my country home. Police officers hauled me off in handcuffs under suicide detention.

What followed was a very dark period; with no family to help me, I relied heavily on my friends. The very same friends assumed the risks with me while climbing, racing bicycles, and riding dirt bikes. We high-fived each other when we succeeded with a daring deed, and then consoled and visited each other in the hospital when things went south. We took care of each others’ homes and kids when someone was on injured reserve.

And this same camaraderie and teamwork pulled me through a year-long child custody battle and got me back on my bikes and out to the cliffs. This group donated and generated funds for my legal expenses, babysat me, and even secured a mortgage to keep my home, the only home my daughter knows. Without this “risky” group of friends, it is quite possible I would not be here typing this.

This isn’t an editorial generated by sitting on the fence and merely observing. I lived the consequences of the risk I took, all of them, right down to the potential loss of my family, physical abilities, job, and home. And considering the suicide watch and detention, the possibility of losing my life.

What Does the Research Say?

It’s clear that some are more prone to accepting risks and the potential negative consequences, such as physical injury or financial loss. What drives certain people to throw themselves into the void, especially when the consequences are heinous and obvious?

Some researchers argue that people engage in these potentially dangerous behaviors because the long-term, negative consequences of these behaviors are outweighed in their minds by the short-term, positive consequences that they produce. Simply put, some need instant gratification. These people may chase the endorphin high, the adulation of friends, or the bolstering of self-confidence with little regard to effects far down the road.

Mackenzie Steiner, a climbing friend of over 25 years and a psychologist who served veterans through the VA for 20 years, studied risk-taking behavior in graduate school for nearly 8 years. She added, “What stands out most from the research over the years is the relationship between the trait of ‘impulsivity,’ or the ‘jump first, think later principle’.”

Some peg a larger appetite for risk to genetics. It is strange to me to think that being more prone to risky behavior is inheritable. But a 12,675-person study conducted by Penn’s Wharton School found a connection between genes, lower levels of gray matter, and risky behavior.

These associations between risk-taking and brain anatomy are many. There is no one “risk region” in the brain, the study director says. “We find a lot of regions whose anatomy is altered in people who take risks.” Steiner added, “Not surprisingly, individuals with higher testosterone levels are more prone to engage in risk-taking behavior.”

For me, the acceptance of risk and the drive to attain objectives related to such risk stems from childhood trauma, according to Kavita Murthy, Ph.D. Dr. Murthy has been a licensed counseling psychologist in Austin, Texas, for almost 20 years. She was also my psychologist during the time period described here.

“My thoughts are that your attraction to extreme sports and risk-taking behavior comes from the intensity of your isolation in your childhood. What I find often is that the intensity that you crave matches the intensity of the pain and suffering from the past.

“Also, these types of extreme endeavors create a bond with other people that you can finally trust and be trustworthy with your very life. That is pretty powerful stuff that might override the darker negative memories of feeling like you were not supposed to even exist and the long hours you were alone and had to navigate the world on your own without any support and love.

“You are one of the lucky ones that chose to process your pain through something that required persistence, discipline, and intense training, in addition to not being afraid of death. My intense athletes want the high at the moment, but they want to feel alive and connected to something bigger in the world that can prove to them that perhaps the pain of life was worth it.”

Steiner, who is no stranger to trauma, added, “An often overlooked reason came from examining my own risk-taking habits as well as those of the countless veterans I served while working at the VA for 20 years. I came to recognize that some portion of us who keep going back to putting ourselves on the proverbial ‘knife’s edge’ are running from the impacts of trauma. Trauma has a way of creating what I refer to as ’emotional background noise,’ and one of the ways we can get away from it is to ‘crank up the volume’ to drown it out.”

If you had a similar childhood, and your path parallels mine, please know you are not alone.

What Do I Think Now?

About 18 months after the accident, I rode an adventure bike again. After the first day of being scared out of my mind for my knee, it all came surging back. The exhilaration of being at speed over rough terrain, the feeling of nailing a turn exit, the connection to a machine where I knew which way it would bounce. All of it hit me that second day out, and I wasn’t scared, and I didn’t let off the gas in fear of anything.

I sincerely knew the consequences of traveling at speed over rough and sometimes unpredictable terrain. And I accepted them again and will continue to do so. Whether dirt biking, climbing, or cycling, I vote for the area under the curve. I couldn’t care less about the length of the line.

I’m 5 years down that line now, and I’m back to doing all the things. But during this period, I’ve lost quite a few friends who were all doing these things. And I momentarily wonder when I receive the sad news.

When I was younger and not as aware of the consequences of my actions, I often pursued activities and objectives that were high risk and high consequence. I got away with this position in the risk / consequence matrix for a long time. I didn’t suffer any real personal loss until my motorcycle accident.

In the last few years, as I’ve absorbed such losses and feel the impact my actions have on those around me, I’ve gradually drifted toward activities that bring fewer risks and lower consequences.

But I’m certain I’ll never land in the low risk, low consequence quadrant. To me, that is only existing and not living. It’s hedging that the length of the line is the most important aspect. I just don’t feel that’s true.

Until I am physically unable, you will find me anywhere but there. I live for the area under the curve, not the curve itself. And I will raise my daughter to separate risk from consequence.

She, like every individual, will decide on her own where she wants to be on the Graph of Life.