HAPE and HACE. These are four-letter words no mountaineer wants to hear. As forms of altitude sickness, HAPE (high-altitude pulmonary edema) and HACE (high-altitude cerebral edema) respectively equal fluid in the lungs and swelling of the brain. Both are caused by the mal effects thin air has on the body. They are each potentially deadly forms of altitude sickness experienced in the Everest region. But, fortunately, both HAPE and HACE are highly avoidable if you know what to look for.

According to Luanne Freer, a doctor and a founder of Himalayan Rescue Association’s Everest ER clinic at Everest Base Camp, about two percent of trekkers and climbers in the Khumbu Region experience HAPE or HACE. Most are treated immediately and moved to the safety of lower elevations. (Far more people, up to 50 percent of trekkers, Freer said, have headaches and minor altitude sickness by the time they reach Lobuche, a village at about 16,000 feet.)

Tragically, two porters have died this year of altitude sickness, Freer said. Both died in Lobuche, expiring likely from HAPE in their sleep after days of coughing, headaches, and other warning signs.

What to look for? A slight headache from altitude can be normal. But watch for a headache that won’t go away. Shortness of breath and coughing fits are warning signs. Trouble breathing? It’s time to ask for help.

If possible, have your blood-oxygen level checked with a medical device commonly called a pulse-ox meter. Many climbing teams carry these devices to assess expedition members.

In the Khumbu Region, a clinic in Pheriche, a village many trekkers pass through, can assess your health and your body’s adaptation to altitude. At Everest Base Camp, Freer’s Everest ER tent is open to aid trekkers, climbers, Sherpas, and porters in need of assessment from altitude-related maladies.

As I wrote in a previous post, Freer and her team, including Dr. Steve Halvorson, saved a Nepalese cook this year in Base Camp. The young man, working for a climbing team at 17,500 feet, had been sick with headaches, breathing issues, and violent coughing. One morning, his fellow workers could not raise him from sleep.

They brought him to the medical tent — Everest ER — for emergency help. The cook was unresponsive. He had an elevated heart rate and was spitting up fluid and blood. Freer said he may have been just an hour from death.

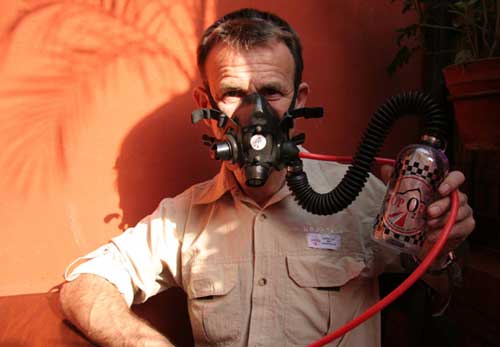

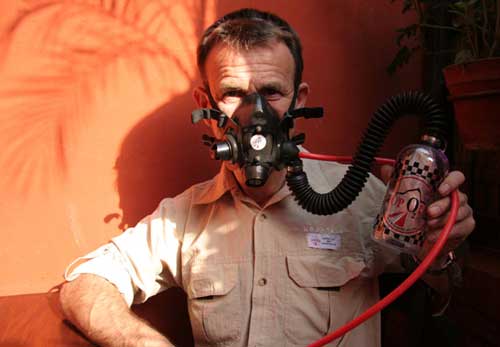

But flowing oxygen plus a medicinal cocktail including diamox, dexamethasone, albuterol, and, oddly, Viagra, revived the patient back from the brink. A Gamow Bag, which is a foldable, human-size sack that simulates lower altitudes, was a tool available at Everest ER. It works with a foot pump, changing pressure in a sealed off chamber.

But for the young cook, the Gamow Bag was not the right treatment, Freer said. Within a couple hours, the patient was talking and responsive. Freer’s team arranged for a transport down-valley to lower elevations, where the cook would receive further evaluation at another Khumbu clinic. “We advised him not to come back and work at this altitude,” Freer said.

For climbers on Mount Everest, the risk of altitude sickness rises exponentially with each day. Headaches, coughing, sleeplessness, hallucinations, and disorientation are common. Above 8,000 meters, a level near the top of Everest dubbed the Death Zone, almost every climber sinks into a stage of altitude sickness.

“HAPE or HACE may affect you up there,” said Jamie Clarke, lead climber for Expedition Hanesbrands,” but they won’t often kill you.” Clarke said the disorientation and exhaustion caused by altitude sickness can lead a climber to simply sit down in the snow and give up. Hypothermia is then the killer, Clarke said.

On his trip to 8,000 meters and beyond, Clarke is prepared to battle the altitude. He has been high on Everest three times, including a summit in 1997. He knows what to look for, what signs signal a necessary descent to a lower camp. On summit day, Clarke and his climbing partner, Scott Simper, will don oxygen masks for the final flank to 29,035 feet. A small stream of air, an oxygen mix fed through a silicon mask, will keep the climbers alert and strong as they kick and step, ever up, toward the top. Despite the thin air, HAPE, HACE, or other four-letter words will not be allowed.

—Stephen Regenold blogged live from the Everest Trail in April 2010.