Few subjects in fishing are simultaneously spoken about with as much authority, marketing, and “Well, I don’t know, but I think it’s worked well enough for me in the past,” dismissal as lure color. And if you, like me, have ever gotten lost during a post-holiday Cabela’s gift card walkabout through the kaleidoscopic menagerie of aisles upon aisles of soft plastics, then you know — no fish species is as subject to the sheer cover-your-basses breadth of options as bass.

There are, of course, the old standby rules: Any lure with white and chartreuse is a surefire shad mimic for clearer water. For the depths, nothing boasts the consistency of a black and blue jig. Muddy water? Toss something black or firetiger to stand out. Somewhere in between gin and chocolate milk? Try watermelon or green pumpkin, but don’t forget the red flakes and hook — unless the bass have been too sensitized to red through some pop lure craze in your area. Then the bleeding gills decal on your crankbait will obviously send them swimming for the hills.

General wisdom shouldn’t be ignored, certainly. However, bass are likely the most studied game fish in North America. We should be able to bring a little more science to lure selection.

So, we sat down with Rebecca Fuller, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor and founder of the now-defunct app BassVision, who studies how fish see the world — and picked her brain on what, when it comes to lures, makes for beauty in the eye of the bassholder.

In short: The world of bass fishing is dominated by tradition. According to most scientific evidence, many of these rules might be wrong. Many mysteries still remain about bass vision. Nevertheless, taking what we’ve proven about how bass see the world and filling in the gaps with personal experience on what lands them, can be the ticket to more tight lines.

The Variables of Vanishing Shades

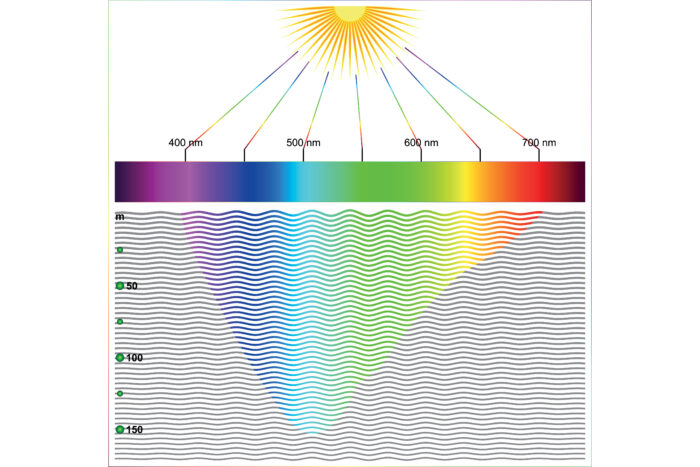

Before we look at how bass see color, we need to know what there is to see. Unlike through air, where the light reflected off surfaces can make it to your eye relatively unimpeded, colors can be swallowed by water rather quickly.

Many anglers may have heard that red is the first to go. This is true — in clear water. There, longer wavelengths attenuate the quickest. Past 15-25 feet, depending on water clarity, red light becomes just another shade of gray. Then goes orange, and so on, with shorter wavelength blues and greens holding out past 100 feet of depth.

However, said Fuller, stained and turbid water are not only a different story from clear water, they also affect light differently from each other.

Stained water itself can be quite clear. Picture a cypress swamp with little current or a blackwater aquarium. The water’s coloration doesn’t come from suspended particulates, but usually tannins, Fuller points out. Turbid water, on the other hand, is simply muddy.

In stained water, everything gets red-shifted. The order in which colors attenuate, essentially reverse — often with a quickness. In heavily stained water, says Fuller, “You go even a meter down, and there’s no UV or blue light.”

Muddy water has a similar reversal of the order in which colors attenuate. Although there, it happens even faster. In a river with heavy runoff, for example, even red may not penetrate more than a few feet.

The Science Behind Vision

Bass have interesting vision. You might remember from biology that there are two main types of photoreceptors in the eye: rods, which handle night vision, and cones, which register color.

Human eyes have three cones: red, blue, and green. Bass, however, are dichromatic, with only two. Fuller’s research has shown that of these receptors, one is sensitive to green, while the other is a complex of twin cells that process red.

Thus, we process the endless aisles of colorful soft plastics far differently than bass. “One way that humans have conceptualized the bass vision system is to put on yellow sunglasses that basically filter out all of the blue,” said Fuller.

It may surprise swearers-by of the classic black-and-blue jig, but bass trained to strike at black or blue targets, in the absence of other scent cues, mix them up constantly. And for fans of white and chartreuse “shad” patterns, bass trained to strike at yellow have trouble not only distinguishing it from white, but occasionally blue!

Some chartreuse dyes might have the advantage of being a bit fluorescent, and thus a bit brighter than pure white underwater, but on the whole, your black-and-blue jigs or white-and-chartreuse spinnerbait might as well be a solid color.

Variation Sensitivity

Bass’s lackluster color processing isn’t surprising. According to Fuller, piscivorous, or fish-eating fish, often only have two color receptors — as opposed to smaller baitfish with more varied diets, who are often rocking up to five. After all, color might not be as important for a generalist predator as pattern recognition, night visual acuity, smell, or sensitivity to vibration.

It’s worth asking how dark it needs to be for bass, a fish that famously loves hugging tight to overhanging structures and burying themselves in weed beds, to switch to night vision. Is it dark enough to a bass in lightly stained water beneath a dock at sunrise, for example, to rely on night vision — rendering the precise color of the creature bait you skip beneath it pointless, as they simply process the contrast between light and dark?

Short answer: According to Fuller, we don’t know. There hasn’t been much research on at what level of light intensity, in what grade of clear, stained, or muddy water, and at what depth, bass switch to night vision.

What is known, said Fuller, is that bass’s visual pattern recognition isn’t great. If you’ve ever seen a bass closely investigating your crankbait, it’s because they can only resolve fine details of that perch pattern from a few feet away, even in relatively clear water.

A good rule of thumb familiar to any topwater fisherman is to keep in mind countershading. Most fish have darker topsides and lighter bottoms so that when viewed from below and above, respectively, their outlines are less visible against the sun and the bottom substrate.

Interestingly enough, similar to how humans have black-and-white-sensitive rod cells distributed around the outer diameter of our retina, bass have more rod cells along the top and bottom of their retina. This aids their ability to distinguish the contrast of prey above and below them.

Still, making bass’s job easy can’t hurt. Many anglers know to opt for black topwater lures for contrast against the moon when night fishing, or to go with dark patterns to stand out in muddy water. However, Fuller notes that contrast against the actual background, not the rule of thumb, is what makes a lure more visible.

A white topwater might offer more contrast on a moonless night. And while black stands out well in turbid conditions, if the rocks or gravel on the bottom is black, a fluorescent chartreuse jig or red craw would offer far more contrast for a bass striking from above.

Bass Voracity

So, longer wavelengths generally attenuate more quickly in clear water, with that procession flip-flopping in stained or muddy water. Bass see red and green most clearly, with mediocre pattern recognition, and a keen eye for contrasting silhouettes. But what, visually, makes them want to strike? Are there some colors or patterns that tend to elicit more aggressive behavior — either predatory or protective?

“If it were as easy as ‘There’s one color that makes them bite,’ we would’ve figured it out by now,” says Fuller.

Some research has turned up a preference for red, but these results are sporadic, and can often be, in large part, attributed to bass’s innate ability to easily distinguish the color. However, bass’s behavior does tend to change when smell and darkness become factors.

Bass are not, I repeat, are not, primarily suction feeders. Bass use both ram (basically swim-sprinting to mouth-tackle prey) and suction (drawing prey in by creating a vacuum in their mouth). Though famous for the latter, they lean toward ram-feeding under most conditions.

In studies that have disabled their lateral line, bass tend to still stalk, surge, and suck much as they normally do, just at shorter ranges. However, in the dark, they tend to do much less stalking and surging, and prefer to make up for lack of targeting info by just sucking down as much water as possible.

So, for lures that kick out less vibration (think a dead-sticked drop shot in a stream), more realistic lures that pass closer inspection — and for nighttime topwater, understanding that bass are less keen to tail a lure for long might help you land more fish.

The Bass Vision Verdict

Picking a color lure to pull out of your tackle box, or if you should fish a pattern differently, can be as simple or complex as you make it.

If you want to think scientifically, keep in mind that color selection comes down to what light survives at the depth you’re fishing, what the colors bass can see, how well it contrasts against the background, and the slight influence that color can have on bass behavior.

If you want to keep it simple, throw some mix of white, black, red, and green. For my money, I keep one extra of everything in a red, orange, and green bluegill pattern.

Ultimately, in few areas does color matter as much as in the potential for sensitization. Even with ones they have trouble distinguishing, associate a color with a reward or smell, and bass quickly get better at discerning hues.

There is enough evidence to believe that while their tendency to generalize the experience of being hooked to a whole class of lures or presentations, sooner or later, bass can get wise and avoid the same old painful same old. After all, even hungry bass still inspect lures.

Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, and that sexy shad pattern might look less nice.