Kyle Ranson is worried about both of his outdoor brands. He’s the founder of Portland-based e-bike maker Vvolt and the CEO of Showers Pass, which makes technical apparel. Like much of the U.S. economy, Ranson relies on the import of products and materials made in China. And for over 25 years, business has mostly been good.

But the last few years, rising tariffs on those imports — levied by President Donald Trump in 2018, and continued by President Joe Biden — have made it difficult to grow his businesses or invest in the future, he said. Now, with Trump proposing even higher tariffs on China on the first day of his new administration, Ranson said he’s uncertain how the outdoor industry can cope.

“It’s absolutely catastrophic and will cause chaos in the industry — it already is,” he told GearJunkie. “I know several brands that are trying to sell, and it will force many small businesses to close.”

Across the outdoor industry, a dozen business leaders and trade organizations interviewed by GearJunkie said that increased tariffs on China would deeply impact their brands — in some cases, for the better.

While the majority of the outdoor industry relies on Chinese manufacturing, brands selling U.S.-made products actually welcome increased tariffs as a way to persuade more companies to keep production inside the country. But even they agreed that small businesses deserve some incentives to attempt the transition.

With Trump now proposing even higher tariffs on China, many outdoor brands may have to raise prices, delay product releases, and freeze hiring — and that’s if they can keep the doors open at all.

Whether they’re likely to win or lose from changing U.S. trade policies, all the brands interviewed for this story agreed on one thing: expanded tariffs on China will have major consequences for the outdoor industry.

Could Tariffs Boost U.S. Manufacturing? Maybe

The argument for tariffs is they can force American companies to move production and manufacturing to the U.S., creating more local jobs and stimulating the economy. But even many outdoor brands with production in the U.S. still rely on parts or materials imported from China. And for certain gear, like bicycle drivetrains or PFAS-free fabric, nearly all production is located in other countries.

Some businesses — like Ranson’s — could certainly move more of their production to the U.S., he said. But that’s a years-long process requiring massive investment. Bigger outdoor companies might be able to afford that, Ranson said, but smaller ones will have a tough time. (Patagonia and The North Face declined to comment for this story.)

“We’ve mapped it out. Final assembly here in the U.S. is viable,” he said. “But for it to be really viable, we need tariff relief on bringing in certain parts. And if you’ve got competition importing bikes duty-free, it becomes completely non-viable.”

Ranson is referring to something called the De Minimis exception. It’s a caveat to U.S. tariffs that allows products valued less than $800 to enter the country duty-free. So as American companies face higher tariffs, they’re still competing with cheaper Chinese brands, many of them available through Amazon.

That’s not the only problem. Many small and medium-sized brands are already facing cash flow issues from paying steeper tariffs for the last few years while trying to maintain prices amid rapid inflation. And it’s hard to make big investments when American trade practices have become so uncertain, Ranson said. That’s why he’s postponing hiring and new products that he’d planned for 2025.

“We’re in a crazy situation in this industry when we’re planning for the unknown. All you can do in that environment is be conservative,” he said. “It’s the unknown that’s so scary.”

Some U.S. Brands Will Flourish

Increased tariffs won’t spell doom and gloom for all U.S. companies, however. American brands already producing here will have a strategic advantage if their competitors have to raise prices for gear made across the Pacific Ocean.

Take OTTOLOCK, for example. The Oregon-based brand has found a niche within the bike-lock marketplace with the Cinch Lock. This super-portable lock (which also made GearJunkie’s list of Best Bike Locks) represents the majority of OTTOLOCK’s business — and it’s made entirely in the USA. Well, almost entirely. Of the lock’s 29 components, only a single one comes from China — but it costs a nickel.

“So there’s zero impact on getting a tariff on a nickel. This actually helps us,” OTTOLOCK founder Jake VanderZanden said. “We do not have to increase prices in any way. We’re actually bullish on the impact to our specific business.”

In the long term, VanderZanden is hopeful that increased tariffs on China could force many companies to move manufacturing to the U.S. That would mean more jobs for U.S. residents, and perhaps lead to a U.S. economy less reliant on overseas labor. “I’m an old U.S. manufacturing guy, and I fully support bringing it back,” he said. “It’s just not simple.”

And it’s even less simple for parts of the outdoor industry without any existing means of production. For example, VanderZanden also runs a bike wheel business called HiFi Sound Cycling Components. Most of the rims and hubs come from China, so that brand will “definitely be hurt” by higher tariffs, he said. It’s especially difficult because smaller brands don’t have the cash flow to handle sudden changes to tariffs, giving a major advantage to larger, existing brands.

Even under current trade conditions, however, it’s possible for brands to refocus on U.S. manufacturing, said Andy Techmanski, founder of outdoor apparel brand FORLOH. The brand sells its U.S.-made apparel at the same prices as competitors relying on Asian factories, proving that “a business can be profitable while manufacturing here in the USA,” Techmanski told GearJunkie.

“There is a huge opportunity not only for us, but for other brands to bring manufacturing back to the USA,” he said.

In fact, he’s hoping for 25-30% tariff increases, which he thinks is steep enough that it could funnel more foreign manufacturing back to the U.S.

“But beyond that, we need American consumers to get behind this movement and realize the net benefit to the U.S. economy,” Techmanski said. “The solution starts with the consumer realizing this, and making the decision to buy USA-made products.”

Outdoor Brands Ask for Trade Program

In 2018, Trump approved new tariffs on China ranging from 7.5% to 25% on billions of dollars’ worth of imported goods. That increased annual duties for many American businesses, including in the outdoors industry.

Then, in December 2020, Congress didn’t renew the country’s oldest trade program, known as the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). The program, which has existed since 1975, grants free trade to certain developing countries. After Trump passed the 2018 tariffs, many outdoor brands moved their production to countries approved by GSP. When it lapsed, they were left with debt from the effort of moving, but not the benefit of cheaper trade.

Since then, outdoor brands have been shelling out major bucks in duties every year just to keep production humming along. Since GSP expired in 2020, NEMO Equipment has paid $850,000 in duties “on down sleeping bags and travel goods imported from GSP beneficiary countries that otherwise could have been used to reinvest in our employees, U.S. operations, and innovation,” the company’s COO Brent Merriam said in an email.

Big Agnes has also paid “hundreds of thousands of dollars impacting our bottom line,” president and co-founder Bill Gamber said.

“Our goal at Big Agnes is to make the best camping gear on the planet and get people in the backcountry and not delve into politics,” Gamber added. “That said, we have been significantly impacted by various tariffs and the delayed reauthorization of GSP.”

In total, the outdoor industry has “endured the burden” of approximately $1.7 billion in additional tariffs since 2020, “stifling innovation, job growth, and creating offshore manufacturing disruptions,” Kent Ebersole, president of the Outdoor Industry Association, said in a news release.

Trump Proposes Additional Tariffs

NEMO’s Merriam maintained that it’s pointless to speculate on what will happen with tariffs until Trump actually takes office.

“The fact is, no one can be sure whether or what additional tariffs may be levied on imported goods until after the new administration takes office on January 20,” he said. “Until then, we’re focusing on what we can control and might be able to influence.”

But Trump has also been clear about his intentions. During the campaign, he suggested a “more than” 60% tariff on all goods from China. Trump, along with some Republican members of Congress, has also called for revoking China’s trade status, triggering duties 10 times higher than imports from other countries. That would put China in the same trade category as Russia, Belarus, Cuba, and North Korea.

“Insiders indicate these proposed tariffs will be the focus of the first 100 days of Trump’s second term as those are expected to be ordered without congressional approval and are not contingent on any type of negotiations,” according to a Reuters analysis.

As for the GSP, Congress hasn’t taken action to renew it. And there are no current signs that Trump would support it, according to Reuters, given that he removed benefits for certain products and countries from GSP during his first term.

Small Businesses Struggle

The tariffs may affect more than just outdoor apparel brands and bike makers. Brick-and-mortar businesses are suffering, too, though perhaps few retail categories have faced headwinds steeper than bike stores.

On January 1, 2025, Biden’s expanded tariff on most e-bikes and e-bike batteries imported from China will go into effect. E-bikes have been the fastest-growing segment of the bike industry for several years. That’s especially significant given that the bike industry at large has stalled a bit since peaking during the pandemic.

But the increased tariffs have taken a toll on e-bikes. The additional costs are passed down to retail stores, many of which can’t convince enough customers to buy them at higher prices. That’s what happened to Cynergy E-Bikes in Portland, which announced its closure on Dec. 5. It’s the fourth Portland bike shop to close its doors this year, according to Bike Portland.

“It is with a heavy heart that after 10 years in business we are throwing in the towel on our retail e-bike business,” Cynergy E-Bikes owner Sami Khawaja wrote in a farewell email to customers. “We simply cannot compete with the internet and Amazon.”

If higher tariffs are about encouraging American manufacturing, it makes sense that certain industries — like bikes — would be granted an exception, said John MacArthur, a professor at Portland State University who studies the bike industry.

“What’s different about this industry from other industries like cars or steel is that there’s no existing production in the U.S. that we’re protecting,” MacArthur said. “The idea that cheap bikes are coming from China through the internet is true, but the companies that are local are also producing their bikes from overseas…. Ideally, we want more manufacturing here, but we should do more to support building that before we penalize it.”

Get Ready for Higher Prices

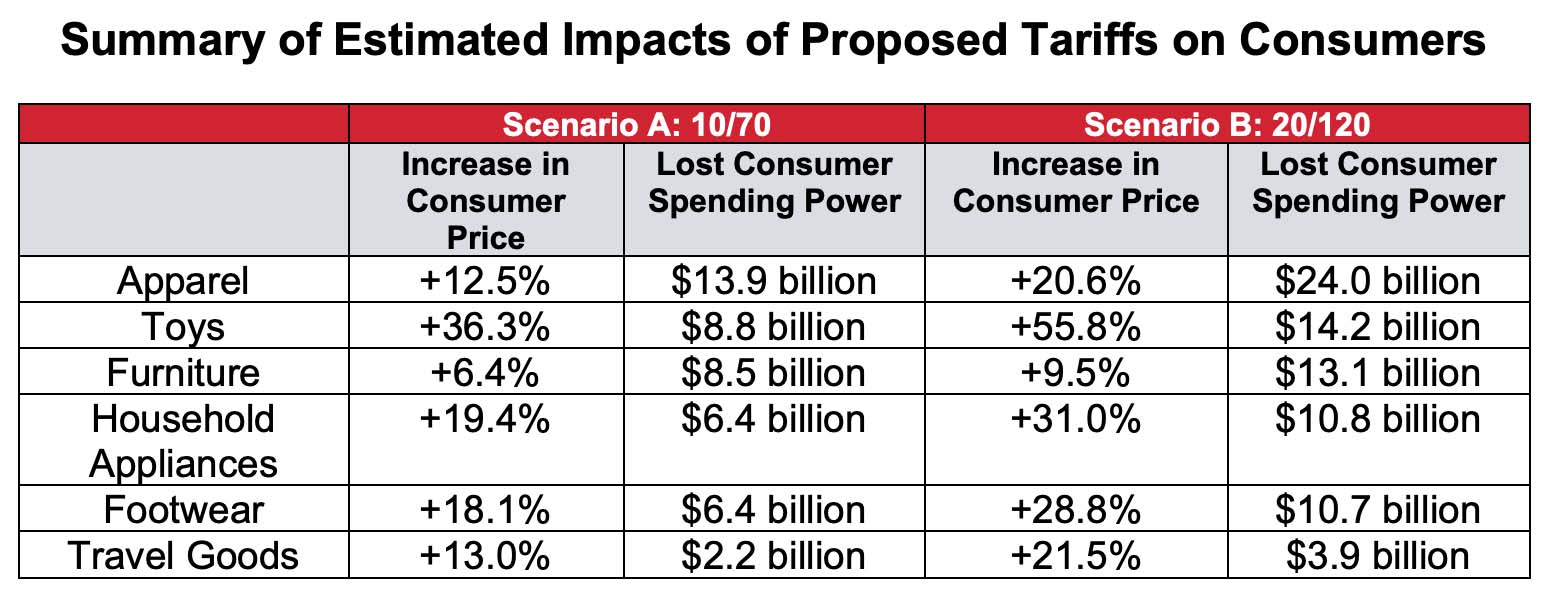

It’s easy to crunch the numbers on what higher tariffs would actually mean for U.S. consumers. According to a November report from the National Retail Federation (NRF), the tariffs proposed by Trump “would have a net negative impact on the United States, with results ranging up to $7,600 in additional costs annually per household.”

The report even estimates price hikes for specific products based on Trump’s proposed tariff increases. A pair of $80 jeans could go up $16, while a $100 winter coat is likely to cost $20 extra.

“Even after accounting for domestic manufacturing gains and new tariff revenue, the result is a net $16 billion to $18 billion loss for the U.S. economy, with the burden carried by U.S. consumers,” the report said.

Raising prices is likely what State Bicycle Company will have to do starting in January, company president Medhi Farsi said last week. State Bicycle is now paying an additional 25% tax for many of its Chinese parts, Farsi said. Though the situation looks dire, he’s trying to be optimistic. He’s hoping that State Bicycle can diversify its supply chain, though he acknowledged “that’s not easy and also comes with increased costs.”

And the consumers hit the hardest by price increases won’t be the ones already serious about cycling, Farsi said. Those riders will likely still pay extra for a top-end road bike. But adding $100 to a kids’ bike? That can be a dealbreaker for many parents.

“If we knew what was going to happen, we would do the work to make the adjustment and change our supply chain. But you can’t make long-term decisions in this type of environment,” he said. “I feel that we’re a contributing part of the economy, even if our stuff is made overseas. We employ dozens of people getting checks every year. We pay millions of dollars in taxes.”

And because of a lack of existing bike facilities in the U.S., it’s unlikely most brands will try to move production back to the U.S., even with the higher tariffs. They’ll simply try to move production to another country, he said, and deal with the increased shipping costs.

“I’m not hearing anybody talking about moving their operations from China to Phoenix,” Farsi said.