The Flatirons, the venerable sandstone area in the Boulder Mountains, have long been a cornerstone in American rock climbing. People scrambled and established moderate multipitch routes here as early as the 1930s. Starting in 1985, some of America’s earliest sport climbs began to appear on their steeper flanks. They mainly climbed smooth, slabby faces on crimps and pebbles, with a few forays into overhanging terrain on pockets, cobbles, and huecos.

These early climbs departed from the status quo, from what we today call trad climbing. And routes had not always had the most imaginative monikers. First ascensionists often took cues from a climb’s geographic qualities (Northwest Corner) or the first-ascent party’s last names (Goss-Logan).

But the new wave of sport climbers had a chance to flex their creative muscles when naming climbs. These climbers wore garish Lycra leggings, tight tank tops, flashy, multicolored shoes, and neon chalk bags. Some brought boomboxes to the cliff and named some of their bolted climbs for lyrics, songs, or albums.

In the Flatirons, we had Violator (a 1990 Depeche Mode album), Superfresh (borrowing from rap terminology), and Slave to the Rhythm (a 1985 Grace Jones album and song).

Boulder native Dan Michael established Slave to the Rhythm in 1987. I first tried the route in 1991. It was already semi-famous for being so overhanging, the colorful rock peppered with tweaky pockets and a dizzying array of cobbles that made it barely climbable.

I didn’t return until 2014, 23 years later, when the route still had its original name. Slave to the Rhythm didn’t rub anyone wrong. But social-justice activism was in relative infancy at that point — at least in the climbing community.

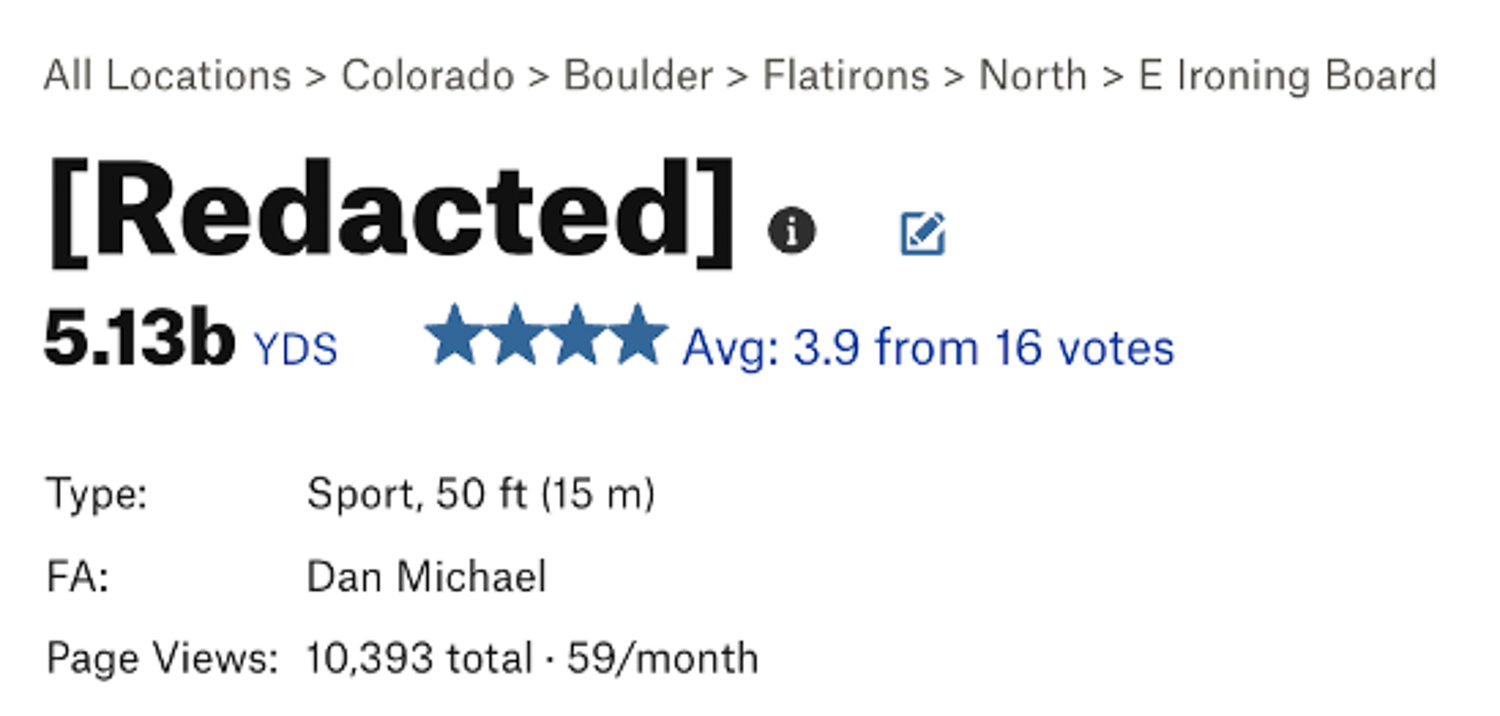

In 2020, the climbing community at large pushed to change problematic route names. This was part of the society-wide movement to address social injustice and systemic racism, and to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The police murder of George Floyd turbocharged it. And Slave to the Rhythm, at least on Mountain Project, the most popular online route guide, became [Redacted], along with a slew of other climbs.

The censorship of route names grew exponentially over the next few years. An internal source at Mountain Project communicated that in August 2022, the site redacted over 6,000 route names. Perusing its database shows that some climbing areas had half or more of their route names redacted.

And the same source reported this week that there are almost 6,000 route names up for review in just one region of Mountain Project.

Have these redactions at Mountain Project and the movement to rename routes gone too far? Where is the line between harmful and just offensive? And should anyone other than the first ascensionist be able to change a route name?

Mountain Project Redacts Route Names

Nick Wilder, former MP owner and current admin, wrote in an August 2020 post that Mountain Project “staff and internal volunteers have reviewed flagged names and have redacted 700 route names that have been deemed overtly discriminatory and in need of quicker action. For these routes, Mountain Project shows ‘[Redacted]’ instead of the original route name.”

This happened as part of Mountain Project’s own big DEI push. Around the same time, the American Alpine Club launched an initiative called Climb United to tackle these issues. The effort included forming a task force on route naming.

One of these climbs was Slave to the Rhythm. Wilder said this was not an initiative to rename routes but instead an effort to place limits on “what we will publish on Mountain Project. For names we won’t publish, we show “[Redacted].’”

Essentially, “[Redacted]” serves as a placeholder until a new name emerges — perhaps suggested by the first ascensionist or via community consensus. Or until this whole thorny mess somehow gets sorted out.

In climbing, changing a route name without the input or permission of the first ascensionist is akin to renaming a work of art without the artist’s consent. The practice might be morally defensible if the first ascensionist refuses to change a harmful route name, or if they have passed away and can no longer provide input. But how should we delegate the authority to make this call in a way that avoids overreach?

Questionable Route Names: History

Discussions about route names are not entirely new. Back in the 1980s, there was a magazine called Mountain out of the United Kingdom. It had news about new crags and first ascents on its front pages.

At one point, an uproar erupted in Mountain’s letters section over a new climb with a Holocaust-themed name that had been reported. The abhorrent name played with gruesome imagery from the concentration camps.

I was 17 then, just a punk kid who liked to go bouldering with his friends after school and smoke weed. I remember thinking, “That’s a terrible route name.” But I wasn’t intellectually sophisticated enough to understand the gravity of it beyond the surface level (too much bouldering, too much weed).

Still, even without knowing the first ascensionists’ intentions — Shock? Irony? Sincerely held Nazi sympathies? — I could tell something was off and that this route name didn’t “belong.”

We Are the Culprits

I’m not going to soft-pedal things. I’m a cisgender, heterosexual, middle-aged male with white skin. I live in a country founded on stolen land, its economy built on the gruesome engine of slavery. And, even centuries after these horrors were first perpetrated, I enjoy the ease of moving through the world — including the climbing world — conferred by my sexuality, age, status, and skin color.

This essay is perforce written from that perspective. It’s the only one I can ever know firsthand, and I don’t pretend otherwise. Guys like me have been setting the tone for the sport, in terms of first ascents and route names, for decades, mostly to good effect — but not always.

This is why the effort to rename routes came from a good place: one of reducing social exclusion in climbing. People of all backgrounds, histories, and perspectives should never feel unsafe or unwelcome at the rock.

Where we failed, however, was in addressing nuance and intention.

Climbing Route Names: Harmful vs. Offensive

During one of the Climb United Zoom meetings, pro climber Nina Williams made an excellent point: If we’re going to redact route names or rename them, we need to distinguish between harmful names and those that are merely offensive.

Harmful route names are obvious. They use racial slurs or tropes that aren’t acceptable in any context. They perpetuate hate and can make climbers feel unsafe at the crag.

But offensive route names are more challenging to pinpoint. What offends you might not offend me, and vice versa. These names might refer to sex or genitalia, or rely on potty humor or ribald wordplay.

Examples of offensive names are manifold in the climbing world: Phallus, Sleepy PeePee, or Daily Dick Dose. To some, these names may be juvenile or disrespectful of the stone, but are they promulgating hate or directly harming anyone? To me, it sure doesn’t seem like it.

The problem with redacting a route name like Slave to the Rhythm is that, as basic research will show, it’s neither harmful nor offensive. That is, unless you consider the word “slave” harmful per se and ascribe the worst possible intentions to the first ascensionist. The first ascensionist named the route after an avant-garde album and song by a celebrated, cutting-edge Black artist. If you listen to the lyrics and watch the video, you’ll see that the song does not have a racist viewpoint.

However, it does reference slavery and maybe gives a nod to how the recording industry exploits hungry artists. (“Work to the rhythm, Live to the rhythm, Love to the rhythm, Slave to the rhythm,” Jones sings.)

But whoever threw this route into the “[Redacted]” hopper didn’t bother to do any research. It seems like they simply saw the word “slave” and flagged the climb. End of story.

And now, nearly three years later, it and many other route names that likely shouldn’t be redacted remain so. And it seems like nobody wants to address this now that the furor of 2020 has abated.

Current Situation on Climbing Route Names

So what’s to be done with routes like Slave to the Rhythm that remain caught in “[Redacted]” limbo on Mountain Project, and as a result, possibly in future guidebooks?

Do we restore their original names in cases where further study or community consensus finds them unharmful? Rename them via an online community vote? Keep them redacted forever despite the utter lack of creativity or inspiration of “[Redacted]” as a route name? Task a route-renaming committee, be it national or local, to go through each route on a case-by-case basis and suggest new options?

As someone who puts up a lot of routes and must come up with names frequently, which is not as easy as you think, I’d hate to see all future route names become anodyne out of fear of them becoming “[Redacted].”

Surely there’s still room for first ascensionists to be creative, playful, and even offensive with their route names — in the historically countercultural vein of our sport — so long as these names aren’t harmful.

Of course, who gets to decide what’s harmful or merely offensive isn’t black-and-white. But I’d warrant that now, with our community’s improved awareness of the issues, climbers will quickly flag patently harmful route names. And peer pressure alone may make first ascensionists reconsider poor route-naming choices.

Since the original furor over route names, Mountain Project has posted a route name review process outlining redaction and how to rectify it if someone thinks it’s an error. It also specifies that the first ascensionist or route developer must rename the route. If they are deceased, Mountain Project will do its best to contact climbing partners, family, friends, or the local climbing organization for an honorary route name.

Print guidebook authors and publishers are also following suit. For instance, the formerly named Slavery Wall in Ten Sleep Canyon, Wyo., now appears as Downpour Wall in recently released guidebooks. But, minus the urgency of 2020, it feels like the discussion is on hold.

Conclusions

I contacted Dan Michael, who established Slave to the Rhythm, to get his thoughts on the matter. He confirmed that he named the route after the Grace Jones song. I asked how he felt about the redaction. It was clear he wasn’t losing much sleep over it, even if one of his signature routes from the 1980s had been renamed.

“I just liked the name,” he wrote in an email. “Yeah, it’s weird that a computer program deleted it, but what ya going to do?”